Beginning with How to Discuss Abstract Ideas in Sign Language, this guide delves into the fascinating world of visual communication for complex thoughts. It acknowledges the inherent challenges of translating abstract concepts into any language and explores how these difficulties are uniquely amplified within a visual-gestural modality.

We will navigate the distinctions between concrete and abstract ideas, illuminate the crucial role of context, and equip you with foundational strategies for effectively breaking down and communicating complex notions. This exploration promises to unlock new avenues for understanding and expression in sign language.

Understanding the Nuances of Abstract Concepts in Communication

Communicating abstract ideas presents a universal challenge across all forms of language. These concepts, lacking direct physical representation, require a deeper level of shared understanding and interpretation. In visual-gestural languages like Sign Language, these inherent challenges can be amplified due to the reliance on spatial relationships, manual signs, and non-manual markers to convey meaning that is not immediately observable. The process demands a sophisticated interplay of linguistic elements to bridge the gap between the intangible and the perceivable.The effectiveness of any communication hinges on the ability to accurately translate internal thoughts and ideas into a shared medium.

Abstract concepts, by their very nature, are not tied to specific, tangible objects or actions. Instead, they represent ideas, qualities, emotions, or states of being that are often subjective and open to interpretation. This necessitates a robust linguistic framework capable of representing these intangible notions, a task that requires careful consideration of vocabulary, grammar, and the cultural context in which the language operates.

Distinguishing Concrete and Abstract Concepts

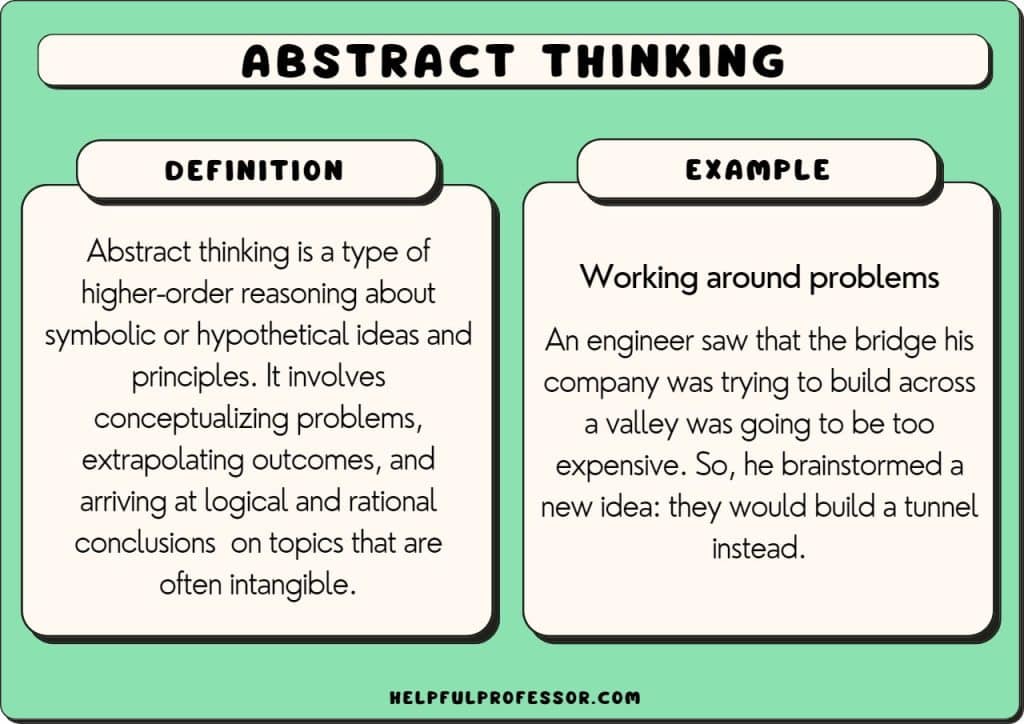

The fundamental difference between concrete and abstract concepts lies in their tangibility and direct perceivability. Concrete concepts refer to things that can be directly experienced through our senses – seen, touched, heard, smelled, or tasted. They are physical entities or actions that exist in the observable world. Abstract concepts, conversely, represent ideas, qualities, emotions, or states that cannot be directly perceived by the senses.

They exist in the realm of thought, imagination, and feeling, and are often more complex and nuanced.To illustrate this distinction, consider the following examples:

- Concrete Concepts: These are concepts that refer to physical objects or readily observable actions. Examples include “chair” (a tangible piece of furniture), “run” (a physical action), “tree” (a visible plant), “water” (a substance we can see and feel), or “loud” (a sound quality we can hear).

- Abstract Concepts: These concepts represent intangible ideas, feelings, or qualities. Examples include “love” (an emotion), “justice” (a principle of fairness), “freedom” (a state of being), “beauty” (an aesthetic quality), or “time” (a dimension that cannot be directly perceived).

The ability to differentiate between these two types of concepts is crucial for effective communication, as the linguistic strategies employed to convey them often differ significantly.

The Role of Context in Abstract Thought Comprehension

Context plays an indispensable role in shaping the understanding of abstract thought. Since abstract concepts lack direct referents in the physical world, their meaning is heavily reliant on the surrounding circumstances, shared knowledge, and the specific situation in which they are communicated. Without adequate context, abstract ideas can become ambiguous, leading to misunderstandings or misinterpretations. The broader the context provided, the clearer and more precise the intended meaning of an abstract concept becomes.This reliance on context is particularly pronounced in visual-gestural languages.

The spatial arrangement of signs, the facial expressions accompanying them, and the overall communicative environment all contribute to the interpretation of abstract ideas. For instance, the concept of “sadness” might be conveyed through a specific sign for emotion, but the intensity and specific nature of that sadness would be further clarified by the signer’s facial expression, body posture, and the preceding conversation.Context can be established through various means:

- Situational Context: The immediate environment and the ongoing interaction provide crucial cues. Discussing “hope” during a difficult time will carry a different weight and meaning than discussing it in a celebratory moment.

- Cultural Context: Shared cultural understandings and values influence how abstract concepts are perceived and expressed. A concept like “honor” might have specific cultural connotations that are not universally understood.

- Linguistic Context: The signs and grammatical structures used within the discourse provide a framework for understanding. A series of related signs can build upon each other to elaborate on an abstract idea.

- Personal Context: The shared history and relationship between communicators can also influence the interpretation of abstract ideas. An inside joke or a shared experience can imbue an abstract concept with specific, personal meaning.

Therefore, when discussing abstract ideas, it is imperative to establish a clear and comprehensive context to ensure that the intended meaning is accurately conveyed and understood.

Foundational Strategies for Expressing Abstract Ideas

Discussing abstract ideas in any language requires a deliberate approach, and sign language is no exception. The key lies in translating intangible concepts into a communicable, visual format. This section will explore foundational strategies that empower effective communication of abstract thoughts within the framework of sign language, emphasizing clarity, shared understanding, and systematic breakdown of complexity.The transition from an abstract thought to a series of signs involves a cognitive process of deconstruction and reconstruction.

It’s about finding concrete representations for concepts that don’t have a direct, one-to-one visual equivalent. This requires creativity, a deep understanding of both the abstract idea and the linguistic capabilities of sign language, and a commitment to ensuring the message is received as intended.

Translating Abstract Thoughts into a Communicable Format

Effectively communicating abstract ideas in sign language hinges on several core principles. These principles act as a roadmap, guiding the signer in transforming internal conceptualizations into external, visible expressions. The focus is on making the invisible visible through strategic signing.

Key principles for translating abstract thoughts include:

- Metaphorical Representation: Abstract concepts can often be conveyed through established or newly created metaphors that draw parallels to concrete experiences or objects. For example, “freedom” might be signed using a bird taking flight, or “connection” could be represented by interlocking hands.

- Categorization and Association: Grouping abstract ideas into broader categories and then associating them with relevant visual cues can aid comprehension. For instance, discussing “justice” might involve signing related concepts like “fairness,” “law,” and “equality” to build a contextual understanding.

- Process and Outcome Visualization: For abstract ideas related to processes or outcomes (e.g., “growth,” “progress,” “change”), visualizing the steps involved or the end result can be highly effective. This might involve signing a sequence of movements that depict a transformation or development.

- Emotional and Experiential Correlates: Many abstract ideas are deeply tied to human emotions and experiences. Signing the associated feelings or physical sensations can provide a powerful entry point. For example, “hope” might be conveyed through a facial expression of optimism and a sign representing looking towards the future.

Breaking Down Complex Abstract Ideas

The complexity of abstract concepts can be a significant barrier to communication. To overcome this, a systematic approach to breaking down these ideas into smaller, more digestible components is essential. This allows for a gradual build-up of understanding, making the overall concept more accessible.

Methods for deconstructing complex abstract ideas include:

- Decomposition into Core Elements: Identify the fundamental components or facets of the abstract idea. For instance, “democracy” can be broken down into “voting,” “representation,” “rights,” and “governance.” Each of these elements can then be signed and explained individually.

- Sequential Explanation: Present the abstract idea in a logical, step-by-step manner. This is particularly useful for abstract concepts that involve a progression or a cause-and-effect relationship.

- Analogy and Exemplification: Utilize analogies and concrete examples to illustrate abstract points. A complex idea like “ethics” can be clarified by presenting scenarios that demonstrate ethical or unethical behavior.

- Hierarchical Structuring: Organize the abstract idea from general to specific, or vice versa. Start with a broad concept and then delve into its more specific implications or components, or begin with specific instances and generalize to the abstract principle.

Establishing Shared Understanding of Abstract Terms

Before embarking on a detailed discussion of abstract ideas, it is paramount to establish a common ground regarding the meaning of the terms being used. Without this foundational agreement, misunderstandings are likely to arise, hindering effective communication.

Strategies for establishing shared understanding of abstract terms involve:

- Pre-definition and Clarification: When introducing an abstract term, take the time to define it clearly using simpler signs or established definitions. This ensures that all participants have a baseline understanding.

- Contextualization through Examples: Provide concrete examples that illustrate the abstract term in practice. This helps to anchor the meaning in tangible situations that can be readily understood.

- Visual Aids and Gestural Reinforcement: Where appropriate, use visual aids or reinforce definitions with descriptive gestures that further clarify the intended meaning of the abstract term.

- Confirmation and Feedback: Encourage participants to express their understanding and ask clarifying questions. This interactive approach helps to identify and resolve any ambiguities or discrepancies in interpretation.

Visual-Verbal Metaphors and Analogies in Sign Language

Sign language, at its core, is a visual language. This inherent visual nature makes it exceptionally well-suited for employing metaphors and analogies that bridge the gap between the abstract and the concrete. By leveraging shared visual experiences and established conceptual mappings, signers can effectively communicate complex ideas that might otherwise be challenging to articulate.The power of visual-verbal metaphors lies in their ability to create immediate understanding by drawing parallels between familiar visual phenomena and abstract concepts.

This section explores how existing visual-verbal metaphors from spoken language can be adapted and how new ones can be creatively developed within the framework of sign language to enhance the expression of abstract thought.

Adapting Spoken Language Visual-Verbal Metaphors

Many abstract concepts in spoken language are already expressed through visual metaphors. These can often be directly translated or adapted into sign language, leveraging shared human perception and experience. The key is to identify the core visual element of the spoken metaphor and find a corresponding visual representation in sign.Here are common types of visual-verbal metaphors from spoken language that can be adapted for sign language:

- Spatial Metaphors: These relate abstract concepts to physical space. For example, “moving forward” in time or progress can be represented by a forward movement of the signing hand. “Being stuck” can be shown by a hand stopping or encountering an obstacle.

- Container Metaphors: Abstract concepts are often thought of as being “in” or “out” of something. For instance, “being in trouble” could be visualized by hands being enclosed or trapped. “Having an idea” might be represented by a hand emerging from the head, signifying an idea “coming out.”

- Path Metaphors: Abstract journeys, like the path of life or a problem-solving process, can be depicted through hand movements that trace a path. A complex problem might be a winding, intricate path, while a simple solution is a straight, direct one.

- Force Dynamics: Concepts involving power, influence, or control can be visually represented. For example, one hand pushing another away could signify resistance or rejection. Two hands clasped and pulling in opposite directions could represent a struggle or conflict.

Designing Novel Visual Metaphors for Abstract Ideas

While many existing metaphors can be adapted, some abstract concepts may require the creation of entirely new visual metaphors. This process involves understanding the core essence of the abstract idea and finding a novel visual representation that is intuitive and understandable within the sign language community.The process for designing novel visual metaphors typically involves these steps:

- Deconstruct the Abstract Concept: Identify the fundamental qualities, characteristics, or functions of the abstract idea. What is its essence? What does it

- do* or

- feel* like? For example, the concept of “understanding” involves clarity, connection, and the integration of information.

- Brainstorm Visual Correlates: Think of concrete, observable phenomena or actions that share similar qualities with the abstract concept. For “understanding,” one might brainstorm visuals like light bulbs illuminating, puzzle pieces fitting together, or two hands coming together to connect.

- Develop a Visual Representation: Translate the brainstormed visual correlates into specific sign language parameters: handshape, orientation, location, movement, and non-manual signals. The goal is to create a sign that is iconic or indexical in its representation. For “understanding,” a sign could involve two hands coming together and interlocking, symbolizing the integration of ideas, or a light bulb illuminating above the head.

- Test and Refine: Present the new visual metaphor to other signers and gather feedback. Is it intuitive? Is it easily understood? Refine the sign based on feedback to ensure clarity and efficacy. This iterative process is crucial for establishing new metaphorical representations.

Conveying Abstract Qualities Through Spatial Relationships and Movement

Sign language’s inherent spatiality provides a powerful toolkit for conveying abstract qualities. The way signs are placed in space, the direction and nature of their movement, and the relationships between signs can all imbue them with abstract meaning.Here’s how spatial relationships and movement can be used to convey abstract qualities:

- Importance: To emphasize importance, signs can be made larger, more emphatic, or placed in a more prominent position in the signing space. Holding a sign for a longer duration or repeating it with greater force can also convey significance. For instance, a sign for “important” might be signed with a strong, deliberate movement originating from the chest and extending outwards.

- Difficulty: Difficulty can be visually represented through signs that involve struggle, resistance, or complexity. This might include signs with jerky or hesitant movements, signs that require two hands to exert force against each other, or signs that are executed in a cramped or convoluted manner. For example, the concept of a “difficult problem” could be signed with hands struggling to untangle a knotted rope-like movement.

- Progress: Progress is often depicted through forward-moving or upward-moving gestures. A smooth, continuous forward motion of the hand can signify advancement, while a series of upward steps can represent incremental progress. The speed and fluidity of the movement can indicate the pace of progress. A sign for “progress” might involve a hand smoothly moving from the back of the signing space towards the front, indicating movement towards a goal.

The strategic use of these spatial and movement cues allows signers to add layers of abstract meaning to their communication, making it rich and nuanced.

Utilizing Non-Manual Markers and Facial Expressions

When discussing abstract ideas in sign language, non-manual markers (NMMs) and facial expressions are not mere embellishments; they are integral components that carry significant meaning. These elements work in tandem with manual signs to provide layers of nuance, emotional context, and conceptual clarity, allowing for a richer and more precise expression of abstract thoughts. Without them, many abstract concepts would remain ambiguous or incomplete.The human face is a powerful communication tool, and in sign languages, its role is amplified.

Facial expressions can indicate the speaker’s attitude towards the abstract idea, their level of certainty, or the intensity of their conviction. These visual cues are crucial for understanding the underlying sentiment and the precise shade of meaning being conveyed, transforming a potentially dry or complex idea into a dynamic and engaging communication.

Conveying Emotional and Conceptual Nuances

Non-manual markers, encompassing everything from eyebrow movements and head tilts to mouth morphemes and body posture, are essential for articulating the emotional and conceptual subtleties of abstract ideas. They act as grammatical markers, adverbs, and even adjectives, enriching the core meaning of the manual sign. For instance, a slight pursing of the lips can indicate contemplation or a hesitant agreement with an abstract concept, while a raised eyebrow might signal surprise or a question about its validity.Facial expressions, in particular, are vital for conveying the emotional valence of abstract ideas.

Consider the abstract concept of “hope.” A manual sign for “hope” could be accompanied by a gentle smile and bright, upward-looking eyes to convey optimism. Conversely, if the context implies a fragile or uncertain hope, the same manual sign might be paired with a more subdued expression, perhaps a slight frown or a downward gaze, indicating the precariousness of the situation.

This ability to imbue signs with emotional color is what allows signers to discuss complex feelings and abstract notions like “justice,” “freedom,” or “responsibility” with genuine depth and personal connection.

Signifying Agreement, Disagreement, Doubt, and Certainty

The ability to clearly signal one’s stance on an abstract idea is fundamental to productive discussion. NMMs provide a sophisticated system for communicating these stances, allowing for precise articulation of agreement, disagreement, doubt, and certainty.Here are some ways specific NMMs can be utilized:

- Agreement: A nod of the head, often accompanied by a slight upward tilt of the eyebrows and a relaxed mouth, typically signifies agreement with an abstract proposition. A sustained nod can indicate strong conviction.

- Disagreement: A head shake, often paired with a furrowed brow and a tightened mouth, clearly indicates disagreement. The intensity of the furrow and tightness can reflect the degree of opposition.

- Doubt: A head tilt to the side, a raised eyebrow, and a slight pursing of the lips are common markers of doubt or uncertainty regarding an abstract idea. This signals a need for further clarification or consideration.

- Certainty: Direct eye contact, a firm, steady expression, and a slight forward lean can convey certainty. The absence of wavering in the NMMs reinforces the speaker’s conviction in their abstract statement.

- Intensity: The intensity of an abstract concept can be conveyed through exaggerated facial movements. For example, expressing intense “frustration” with an abstract policy might involve widened eyes, a furrowed brow, and a sharp, downward movement of the mouth.

Differentiating Similar Abstract Concepts

Subtle shifts in facial expressions are often the key to distinguishing between abstract concepts that might otherwise appear similar. The human face can convey minute differences in meaning that manual signs alone might struggle to articulate.For example, consider the abstract concepts of “understanding” and “knowing.”

- To convey “understanding” of a complex theory, a signer might use a manual sign for the concept, accompanied by a thoughtful expression, perhaps a slight furrowing of the brow and a slower blink rate, indicating processing and comprehension. The eyes might look slightly upward as if recalling information.

- In contrast, to convey “knowing” a fact or principle, the same manual sign might be used but with a more direct and assured facial expression. This could involve a steady gaze, a neutral or slightly confident mouth shape, and perhaps a brief, sharp nod to confirm the knowledge.

Another instance could be differentiating between “liking” and “loving” an abstract idea like “creativity.” “Liking” creativity might be shown with a pleasant, relaxed smile and bright eyes. “Loving” creativity, however, could be expressed with a more profound, perhaps slightly wistful or passionate expression, possibly involving a gentle sigh or a faraway look, indicating a deep emotional connection to the concept.

These subtle, yet distinct, facial cues are vital for precise communication of abstract thought.

Employing Fingerspelling and Lexicalization for Abstract Terms

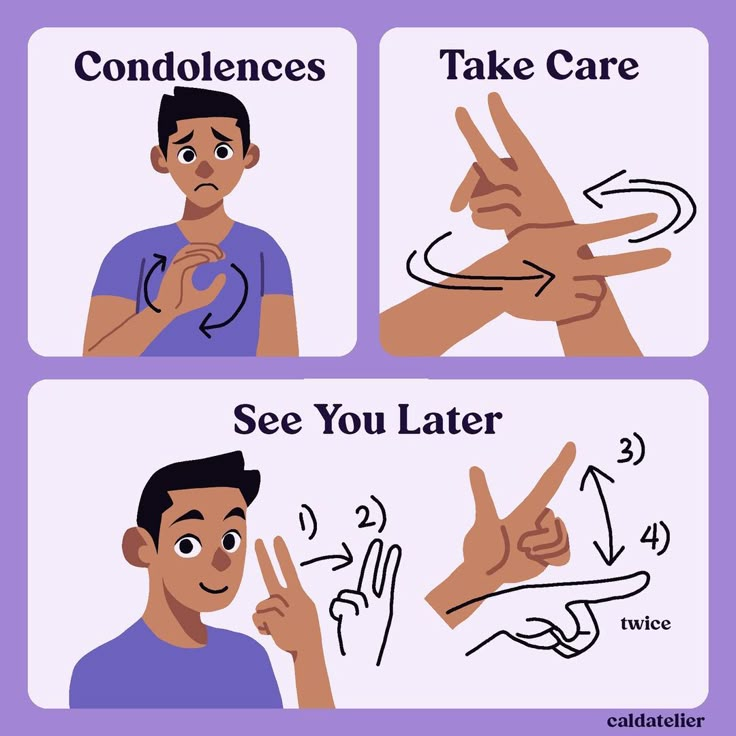

Navigating the landscape of abstract ideas in sign language often requires a thoughtful combination of established linguistic tools and creative adaptation. While many abstract concepts have well-defined signs, there are instances where direct equivalents are less common or absent. In such situations, the strategic use of fingerspelling and the process of lexicalization become invaluable for clear and effective communication.Fingerspelling serves as a direct phonetic representation of words, offering a precise method to convey terms that may not yet have a standardized sign.

This technique is particularly crucial when encountering newly coined abstract concepts or specialized terminology. However, relying solely on fingerspelling for abstract ideas can sometimes be cumbersome and less visually fluid than using a dedicated sign. This is where the concept of lexicalization comes into play, offering a pathway to integrate these concepts more seamlessly into the visual-gestural language. Lexicalization is the process by which a sequence of signs, or a fingerspelled word, becomes conventionalized and recognized as a single lexical unit, often with its own unique sign.

Strategic Use of Fingerspelling for Abstract Concepts

Fingerspelling acts as a foundational bridge for abstract terms that lack established signs within a given sign language. Its primary advantage lies in its precision, ensuring that the intended concept is accurately conveyed without ambiguity. This is especially pertinent when discussing emerging theories, technical jargon, or highly specific philosophical ideas where a universally recognized sign may not yet exist. For instance, a new scientific theory might be introduced by fingerspelling its name before a descriptive sign is developed or adopted.When faced with an abstract term for which no sign is readily available, the Deaf community often employs several strategies:

- Direct Fingerspelling: The most straightforward approach is to spell out the word letter by letter. This is effective for single, complex, or very new terms.

- Descriptive Fingerspelling: Sometimes, a combination of fingerspelling and a brief descriptive sign or gesture can be used to clarify the concept. For example, if a new abstract term relates to a feeling, one might fingerspell the term and then use a sign for “feeling” or a facial expression indicating the emotion.

- Contextual Clarification: The surrounding signs and the overall discourse provide context that aids in understanding a fingerspelled abstract term. The speaker’s non-manual markers also play a significant role in conveying the abstract nature and nuance of the word.

It is important to note that the choice to fingerspell often depends on the audience’s familiarity with the term and the prevalence of the concept within the community.

Developing or Adapting Signs through Lexicalization

Lexicalization is a dynamic process that enriches sign languages by transforming descriptive phrases or fingerspelled words into more concise and iconic signs. For abstract terms, this process can involve several stages, moving from a descriptive representation to a more solidified lexical item. This evolution is crucial for the language’s ability to express complex and nuanced ideas efficiently.Methods for developing or adapting signs for abstract vocabulary include:

- Compounding and Reduplication: Abstract concepts can sometimes be represented by combining existing signs or repeating a sign to add emphasis or specificity. For example, a sign for “thought” might be combined with a sign for “complex” to represent a complex thought process.

- Iconicity and Metaphorical Extension: Signs can evolve to become more iconic, visually representing aspects of the abstract concept. This often involves extending the meaning of existing signs metaphorically. For instance, a sign representing “growth” might be adapted to signify abstract concepts like “development” or “progress.”

- Phonological Reduction: As a fingerspelled word or a descriptive sign sequence gains currency, it may undergo phonological reduction, where certain movements or handshapes are simplified or omitted, leading to a more streamlined sign. This is a natural linguistic process observed across many languages.

- Community Adoption: The most critical factor in lexicalization is community adoption. A sign or a modified fingerspelled representation becomes a recognized lexical item when it is consistently used and understood by the majority of signers.

The development of signs for abstract concepts is often a collaborative and organic process within the Deaf community, reflecting the collective need to express and understand these ideas.

Effectiveness of Fingerspelling Versus Creating a New Sign for Abstract Concepts

The decision to employ fingerspelling or to develop a new sign for an abstract concept involves weighing their respective strengths and weaknesses. Both methods are vital tools, but their suitability varies depending on the context, the nature of the abstract idea, and the communicative goals.Here’s a comparison of their effectiveness:

| Aspect | Fingerspelling | Creating a New Sign (Lexicalization) |

|---|---|---|

| Precision and Accuracy | High; directly represents the written word, leaving little room for misinterpretation of the term itself. | Can be high once established, but initial development may lead to variations in understanding until widely adopted. |

| Efficiency and Flow | Lower; can be slow and interrupt the natural flow of conversation, especially for longer words or complex ideas. | Higher; a single, distinct sign is often more visually economical and integrates smoothly into discourse. |

| Accessibility and Learnability | Accessible to those familiar with fingerspelling; can be a barrier for learners or those unfamiliar with the specific word. | Requires learning the new sign; once learned, it is a direct and efficient communication tool. |

| Universality and Standardization | Relies on shared knowledge of the alphabet and the specific word being spelled. | Aims for community standardization; can be challenging to achieve across different regions or dialects without significant effort. |

| Conveying Nuance | Limited; the nuance is primarily conveyed through surrounding signs and non-manual markers. | Potentially high; a well-designed sign can embody the abstract qualities and nuances of the concept visually. |

| Example Use Case | Introducing a newly defined abstract philosophical concept for the first time in a lecture. | Expressing a commonly understood abstract idea like “freedom” or “justice” that has an established sign. |

Ultimately, the most effective approach often involves a judicious combination of both. Fingerspelling can serve as an initial point of introduction or clarification for a novel abstract term, while the ongoing process of lexicalization allows for the eventual development of more fluid and integrated signs, thereby enriching the expressive capacity of the sign language.

Structuring Complex Abstract Discussions in Sign Language

Effectively organizing a conversation around abstract ideas in sign language is crucial for ensuring that complex concepts are communicated clearly and understood comprehensively. This involves a deliberate approach to introducing, developing, and concluding the discourse, much like structuring any formal presentation or debate. By establishing a logical flow and employing specific techniques, signers can navigate intricate abstract topics with greater ease and precision.A structured approach provides a roadmap for both the speaker and the listener, preventing confusion and allowing for deeper engagement with the material.

This framework helps to break down multifaceted abstract ideas into manageable components, fostering a more accessible and productive communication environment.

Framework for Organizing Abstract Discussions

To ensure clarity and flow in a sign language discussion involving multiple abstract ideas, a systematic framework is essential. This framework can be visualized as building blocks, where each new concept or connection is added logically to the preceding ones. It begins with establishing a foundational understanding, then elaborates on individual components, and finally, synthesizes them into a coherent whole.

This methodical progression helps the audience follow the intricate connections between abstract notions.The framework involves several key stages:

- Introduction of Core Concepts: Clearly define and present the primary abstract ideas that will be discussed. This stage sets the context and ensures all participants share a common understanding of the foundational terms.

- Development of Interconnections: Systematically explore the relationships between the introduced concepts. This involves illustrating how one idea influences, contrasts with, or builds upon another.

- Elaboration and Nuance: Delve deeper into the complexities of each abstract idea, providing supporting details, examples, and explanations to highlight their various facets and implications.

- Synthesis and Conclusion: Bring together the various threads of the discussion to form a comprehensive understanding. This stage reinforces the main points and summarizes the overall message or argument.

Step-by-Step Procedure for Abstract Discussions

A step-by-step procedure ensures that abstract topics are introduced, developed, and concluded in a manner that maximizes comprehension and engagement. This structured process guides both the presenter and the audience through the complexities of abstract thought.The procedure can be Artikeld as follows:

- Setting the Stage: Begin by clearly stating the overarching topic and the specific abstract ideas to be explored. This initial step is akin to laying the groundwork, ensuring everyone is aligned on the purpose of the discussion. For instance, if discussing “justice,” one might first sign the concept of fairness and equality before introducing the more complex notion of distributive justice.

- Introducing the First Abstract Concept: Present the first abstract idea using clear definitions, relevant metaphors, and appropriate non-manual markers. Ensure this concept is thoroughly understood before moving to the next.

- Establishing Connections: Explicitly demonstrate the relationship between the first concept and the next abstract idea. This can involve signing comparative structures, cause-and-effect sequences, or hierarchical arrangements.

- Developing Subsequent Concepts: Introduce and develop each subsequent abstract idea in a similar manner, always linking it back to the previously discussed concepts. The use of transition signs is critical here to guide the flow.

- Illustrating Complex Relationships: Employ visual aids or descriptive signing to showcase intricate relationships between multiple abstract concepts. This might involve drawing diagrams in the air or using spatial arrangements to represent abstract structures.

- Summarizing and Synthesizing: Towards the end, bring together all the discussed abstract ideas, highlighting their interconnectedness and the overall message. This phase often involves a recap of the main arguments or themes.

- Concluding Remarks: Offer a brief concluding statement that reinforces the significance of the discussed abstract ideas or opens the floor for further contemplation.

Illustrating Abstract Relationships with Visual Aids and Descriptive Signing

Visual aids and descriptive signing are powerful tools for making abstract relationships tangible and understandable in sign language. When discussing abstract concepts, the visual-spatial nature of sign language can be leveraged to create mental models that mirror the connections between ideas.Consider the abstract relationship between “freedom” and “responsibility.” To illustrate this, one might first sign “freedom” by creating a wide, open space with the hands, perhaps accompanied by a feeling of lightness.

Then, to introduce “responsibility,” the hands might move closer together, forming a more contained shape, perhaps with a slightly furrowed brow to indicate the weight or obligation.To show the

interdependence* of these two concepts, one could

- Sign “freedom” and then immediately follow with a sign that visually links the two concepts, such as a chain or a bridge, connecting the space of freedom to the space of responsibility.

- Use facial expressions to convey the nuance: a positive, expansive expression for freedom, followed by a more serious, grounded expression for responsibility.

- Employ spatial grammar: placing the concept of “freedom” in one area of signing space and “responsibility” in another, and then drawing a line or an arrow between them to indicate the direct link or flow from one to the other. For example, one might sign “When you have [freedom] (signed with open hands moving outward), then you also have [responsibility] (signed with hands coming together, perhaps with a slight downward motion).” The act of signing these sequentially and then drawing an invisible connection between them visually represents the abstract relationship.

Another example could be illustrating the abstract concept of “progress” in relation to “stagnation.” One might sign “progress” by showing a hand moving steadily upward and forward. To contrast this with “stagnation,” the same hand might be shown remaining in one place, perhaps with a slight rocking motion indicating being stuck. To show the abstract idea that “progress requires overcoming stagnation,” one could sign “stagnation” (hand stuck in place), then sign a struggle or effort (hands pushing against an invisible barrier), and finally sign “progress” (hand moving upward and forward).

This visual narrative clearly articulates the abstract relationship between the two states.

Building Shared Understanding and Clarification Techniques

Establishing a common ground of understanding is paramount when navigating the complexities of abstract ideas in sign language. This section delves into practical methods for ensuring that both the communicator and the recipient are on the same page, fostering clarity and minimizing misinterpretations. It’s about actively engaging in a collaborative process of meaning-making.Effective communication of abstract concepts relies on a continuous feedback loop.

This involves not only expressing ideas but also confirming that those ideas have been received and understood as intended. By employing specific techniques, signers can build confidence in their communication and ensure that abstract notions are grasped with precision.

Checking for Understanding in Abstract Discussions

Regularly verifying comprehension is a cornerstone of successful abstract communication in sign language. This proactive approach prevents misunderstandings from snowballing and allows for immediate adjustments. It demonstrates respect for the other person’s cognitive process and commitment to clear communication.There are several key techniques to incorporate:

- Pause and Observe: After presenting an abstract idea, take a brief pause and observe the recipient’s non-manual markers (NMMs) and facial expressions. Look for signs of confusion, contemplation, or affirmation.

- Direct Comprehension Checks: Utilize specific signs or phrases that directly ask about understanding. These can range from simple nods of inquiry to more explicit signs.

- Summarization Requests: Encourage the recipient to rephrase the concept in their own words or signs. This is a powerful way to assess their level of understanding.

- Contextual Probing: Ask questions that require the recipient to apply the abstract concept to a hypothetical or real-world scenario. This reveals whether they can operationalize the idea.

Rephrasing and Explaining from Different Perspectives

When an abstract concept isn’t immediately grasped, the ability to present it from multiple angles is crucial. This involves breaking down the idea, using different analogies, or connecting it to previously understood concepts. The goal is to find a pathway to understanding that resonates with the individual’s cognitive framework.Strategies for rephrasing include:

- Simplification: Break down complex abstract terms into their constituent parts or simpler related concepts.

- Metaphorical Expansion: If an initial metaphor wasn’t effective, try a different one that might be more accessible. For instance, explaining “democracy” as a shared responsibility in a household rather than just a voting system.

- Concrete Examples: Whenever possible, ground abstract ideas in tangible examples, even if the examples themselves are slightly metaphorical. For “justice,” one might sign about fairness in sharing resources.

- Sequential Elaboration: Present the concept in stages, building upon each explained component. This is akin to constructing a narrative for the abstract idea.

Soliciting Feedback and Asking Clarifying Questions

Actively inviting questions and feedback creates an open environment for learning and clarification. It empowers the recipient to voice any uncertainties they might have, transforming potential misunderstandings into opportunities for deeper comprehension. This collaborative approach ensures that the communication is a two-way street.Effective methods for soliciting feedback and asking clarifying questions include:

- Open-Ended Inquiries: Instead of asking “Do you understand?”, which often elicits a simple “yes” or “no,” ask questions that encourage elaboration, such as “What are your thoughts on this?” or “How does this idea connect with what we discussed earlier?”

- Specific Point Probing: If you sense a particular part of the explanation might be unclear, ask direct but gentle questions about that specific element. For example, “When I signed about the ‘essence’ of the idea, what came to mind for you?”

- Encouraging Sign-Backs: Prompt the recipient to sign back their understanding or a related concept. This can be done by saying, “Can you show me what you understood?” or “How would you sign that concept?”

- Creating a Safe Space: Assure the recipient that it’s perfectly acceptable to ask questions and that there are no “silly” questions when dealing with abstract ideas. This can be conveyed through positive NMMs and affirming signs.

Illustrative Examples of Abstract Concept Communication

This section delves into practical demonstrations of how abstract ideas can be effectively communicated within a sign language framework. By examining specific concepts like “freedom,” “justice,” and “time,” we can gain a deeper appreciation for the visual and gestural strategies employed by signers to convey complex and intangible notions. These examples highlight the interplay of established signs, spatial grammar, non-manual markers, and creative visual representations.Understanding how abstract concepts are signed provides valuable insights into the richness and flexibility of sign languages.

It showcases the cognitive processes involved in translating abstract thought into a visual-gestural modality, offering a bridge for clearer and more nuanced communication between signers and even for those learning to express such ideas.

Signing the Concept of Freedom

The abstract concept of “freedom” can be vividly signed by combining established signs with evocative gestures and facial expressions. A common approach involves the sign for “FREE,” which often depicts hands breaking free from constraints. This can be further elaborated to convey different facets of freedom.For instance, to express personal freedom, one might sign “FREE” with an open, expansive gesture, perhaps extending the arms outwards with a look of relief and liberation on the face.

If the context is political freedom, the signing might involve signs for “COUNTRY” or “PEOPLE” followed by “FREE,” emphasizing collective liberation. The intensity of the facial expression, such as a smile or a determined gaze, plays a crucial role in conveying the emotional weight of freedom. The speed and amplitude of the movements can also indicate the degree or nature of the freedom being discussed.

Discussing Justice in Sign Language

The abstract idea of “justice” requires a multifaceted approach in sign language, often integrating existing signs with spatial configurations and specific non-manual markers (NMMs) to convey its complex meaning. To initiate a discussion about justice, one might begin with the established sign for “JUSTICE,” which typically involves two hands coming together in a balanced or equitable manner, or a hand tapping on a surface to signify fairness.A scenario illustrating this could involve discussing a legal case.

The signer might first establish the context by signing “COURT” or “LAW.” Then, to discuss whether justice was served, they could use the sign for “JUSTICE” followed by NMMs indicating questioning or uncertainty (e.g., raised eyebrows, head tilt). To express a lack of justice, the sign for “JUSTICE” could be negated with a head shake and a frowning expression, perhaps combined with signs like “WRONG” or “UNFAIR.” Spatial language can be used to represent different parties involved in a dispute, positioning them in space and then signing “JUSTICE” in relation to their positions to illustrate fairness or unfairness in their interactions.

Visual Representation of Time and its Dimensions

The abstract concept of “time” is uniquely and effectively represented in sign language through spatial metaphors and specific directional movements. The most common visual representation of time in many sign languages is a timeline extending from the signer’s body.The past is typically represented as being behind the signer, with signs like “PAST” or “BEFORE” involving a backward sweeping motion of the hand.

The future is located in front of the signer, with signs like “FUTURE” or “AFTER” involving a forward sweeping motion. The present moment is often indicated by the signer’s immediate physical space.To convey duration, the signer might use a continuous circular motion with their hand, or a sustained signing of a relevant verb or noun, with NMMs indicating the length of time.

For example, discussing a long duration might involve a slower, more drawn-out signing of the concept, perhaps with a sigh or a look of weariness. Conversely, a short duration could be indicated by quick, sharp movements and a more animated expression. The concept of “simultaneous” events can be shown by signing two separate events at the same level in space, moving at the same pace.

- Past: Indicated by movements behind the signer, often a backward sweep of the hand.

- Future: Indicated by movements in front of the signer, often a forward sweep of the hand.

- Present: Signified within the signer’s immediate personal space.

- Duration: Represented by sustained signing, circular hand movements, or specific temporal signs accompanied by NMMs indicating length.

- Simultaneity: Shown by signing multiple actions at the same spatial level and pace.

Conclusive Thoughts

In essence, mastering the art of discussing abstract ideas in sign language is about building bridges of understanding through visual storytelling and precise communication. By embracing visual-verbal metaphors, leveraging non-manual markers, and employing strategic lexicalization, signers can effectively convey even the most nuanced and intangible concepts.

This journey empowers individuals to engage in richer, more meaningful dialogues, fostering deeper connections and a more inclusive communication landscape. The ability to articulate abstract thought visually is a testament to the expressive power and adaptability of sign language.