How to Learn About Deaf History in America offers a fascinating journey into a rich and often overlooked narrative of resilience, innovation, and cultural development. This exploration invites you to uncover the foundational periods, pivotal moments, and the vibrant tapestry of Deaf life that has shaped the American experience.

We will delve into the establishment of key institutions, the evolution of educational philosophies, and the profound impact of influential figures who championed Deaf rights and education. Understanding the scope of Deaf history in America reveals a dynamic story of community building, linguistic heritage, and the continuous fight for recognition and equality.

Understanding the Scope of Deaf History in America

Deaf history in America is a rich and multifaceted narrative, extending far beyond mere accounts of hearing loss. It encompasses the development of unique cultures, languages, educational systems, and advocacy movements that have profoundly shaped the American experience. To truly grasp this scope, we must delve into its foundational periods, the institutions that fostered community, the educational philosophies that guided learning, and the pioneering individuals who championed the rights and visibility of Deaf Americans.The journey of Deaf history in the United States is characterized by periods of significant progress, challenges, and resilience.

From the earliest attempts at education to the establishment of a robust Deaf community and the ongoing fight for accessibility and recognition, understanding these phases is crucial for appreciating the full breadth of this history.

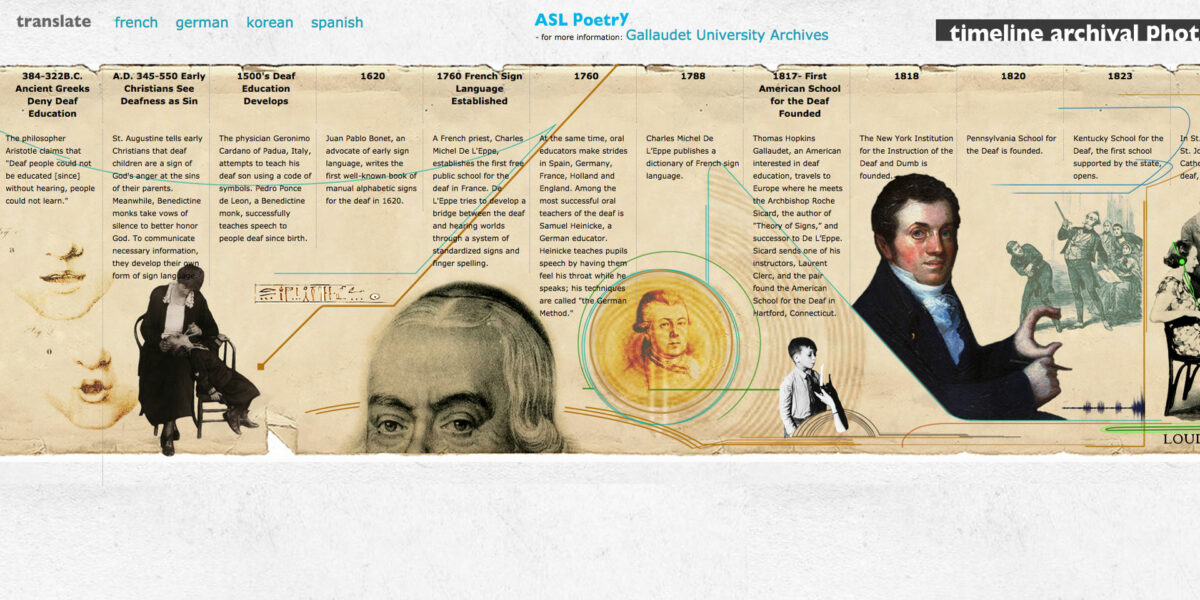

Foundational Periods of Deaf History in the United States

The early history of Deaf individuals in America is often intertwined with the broader colonial and early republic periods. Initially, Deafness was frequently viewed through a lens of disability, with limited educational or societal integration opportunities. However, the late 18th and early 19th centuries marked a pivotal shift with the advent of formal Deaf education. This period laid the groundwork for the formation of distinct Deaf communities and the establishment of enduring institutions.

The subsequent decades saw the consolidation of these early efforts, the development of sign language as a vibrant communication system, and the growing awareness of Deaf culture as a unique and valuable aspect of American society.

Significant Early Institutions and Their Roles in Shaping Deaf Communities

The establishment of early schools for the Deaf was instrumental in creating concentrated Deaf communities and fostering a sense of collective identity. These institutions provided not only education but also a social environment where Deaf individuals could interact with peers and develop their own cultural norms and communication practices.The following institutions played a pivotal role:

- The American School for the Deaf (Hartford, Connecticut), founded in 1817: This was the first permanent public school for the deaf in the United States. It was established by Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet and Laurent Clerc, a deaf teacher from France. The school became a model for future institutions, introducing French Sign Language (which heavily influenced American Sign Language) and providing a structured educational environment.

- The New York Institution for the Instruction of the Deaf and Dumb (now the New York School for the Deaf), founded in 1817: Shortly after the Hartford school, this institution was also established, further expanding educational opportunities for Deaf children in another major population center.

- The Virginia School for the Deaf and the Blind (now the Virginia School for the Deaf and the Blind), founded in 1839: This school, like others that followed, often served both Deaf and blind students, reflecting the educational approaches of the time. Its establishment was crucial for extending educational access to Deaf individuals in the Southern states.

These early schools were more than just educational centers; they were vital hubs for social interaction, cultural development, and the dissemination of knowledge within the Deaf community.

Impact of Early Educational Philosophies on Deaf Individuals’ Lives

The educational philosophies adopted by early schools for the Deaf had a profound and lasting impact on the lives of Deaf individuals, influencing their communication methods, social integration, and overall opportunities. Two prominent, and often competing, philosophies shaped this landscape.The first, often termed the “Manual” approach, emphasized the use of sign language. This philosophy recognized sign language as a natural and effective means of communication for Deaf individuals and was strongly advocated by educators like Laurent Clerc.

This approach fostered a strong sense of Deaf identity and community, as sign language became a unifying force.The second, known as the “Oral” or “Aural” approach, focused on teaching Deaf individuals to speak and lip-read, aiming for integration into the hearing world. This philosophy gained prominence, particularly in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, influenced by international movements like the Milan Congress of 1880, which largely condemned the use of sign language in education.The impact of these philosophies was significant:

- The Manual approach, by embracing sign language, nurtured the development and preservation of American Sign Language (ASL) and strengthened Deaf culture. It provided a linguistic and cultural foundation for Deaf individuals.

- The Oral approach, while aiming for integration, often led to frustration for many Deaf students who struggled to master speech and lip-reading. It also sometimes marginalized Deaf culture and ASL, leading to a period of suppression for sign language in many educational settings.

The debate between these philosophies created a complex educational landscape, with Deaf individuals and their allies navigating the best pathways for learning and life.

Key Figures Who Championed Deaf Rights and Education in the Formative Years

The formative years of Deaf history in America were illuminated by the dedication and vision of several key figures who tirelessly advocated for the education and rights of Deaf individuals. Their efforts laid the groundwork for the robust Deaf community and its ongoing pursuit of equality.Among these pivotal individuals are:

- Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet: A minister and educator, Gallaudet traveled to Europe to learn methods of educating the deaf. His collaboration with Laurent Clerc led to the establishment of the American School for the Deaf, a landmark achievement in Deaf education.

- Laurent Clerc: A deaf teacher from the Royal Institute for the Deaf in Paris, Clerc brought with him a sophisticated sign language system that became a foundational element of American Sign Language. His presence and teaching were indispensable to the early success of Deaf education in America.

- Edward Miner Gallaudet: Son of Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, Edward Miner Gallaudet founded the National Deaf-Mute College in 1864, which was later renamed Gallaudet University. This institution was the world’s first and only university specifically for the education of Deaf and hard-of-hearing students, providing higher education opportunities previously unavailable.

- Harlan Lane: While his most significant contributions came later, Lane’s work as a psychologist and historian has been crucial in documenting and understanding the historical struggles and triumphs of Deaf people, particularly concerning educational philosophies and the suppression of sign language.

These individuals, through their pioneering work, unwavering commitment, and courageous advocacy, fundamentally shaped the trajectory of Deaf history in America, ensuring that education and opportunities would become more accessible for generations to come.

Key Events and Turning Points

The journey of Deaf Americans is marked by pivotal moments that significantly shaped their educational, social, and legal landscape. Understanding these key events and turning points is crucial for appreciating the resilience and progress of the Deaf community. These developments, often born from struggle and advocacy, laid the groundwork for the rights and opportunities available today.

Establishment of the First Permanent School for the Deaf in North America

The establishment of the first permanent school for the Deaf in North America was a monumental achievement, marking a dedicated effort to provide formal education to Deaf individuals. Prior to this, educational opportunities were scarce and largely informal. This initiative provided a structured environment where Deaf children could learn, communicate, and develop a sense of community.The American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, founded in 1817 by Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, Laurent Clerc, and Mason Fitch Cogswell, stands as this pioneering institution.

Gallaudet, after encountering a young Deaf girl named Alice Cogswell, was inspired to seek formal education for her. His journey to Europe led him to Clerc, a Deaf teacher from the National Institute for Deaf-Mutes in Paris, who agreed to return to America and help establish the school. This partnership was instrumental in bringing established Deaf education methodologies to the United States, primarily utilizing a combination of sign language and manual methods.

The success of the Hartford school paved the way for numerous other schools for the Deaf to be established across the nation.

Influence of the Milan Congress of 1880 on American Deaf Education

The International Congress on Education of the Deaf, held in Milan, Italy, in 1880, cast a long and detrimental shadow over Deaf education in America, particularly through its endorsement of oralism. This congress, dominated by oralist proponents, passed resolutions that strongly favored the oral method of instruction (teaching Deaf children to speak and lip-read) and discouraged the use of sign language in schools.The impact on American Deaf education was profound and largely negative.

Despite significant opposition from many American educators and Deaf individuals who recognized the efficacy of sign language, the resolutions of the Milan Congress led to a widespread shift towards oralism in many American schools for the Deaf. This period saw the suppression and often outright banning of sign language in classrooms. Consequently, many Deaf students were denied effective communication and felt isolated, leading to a decline in educational outcomes for some and a deepening of the educational divide.

The legacy of Milan continued to be a point of contention and a driving force for Deaf advocacy for decades, as the community fought to reclaim and preserve their language.

Societal Shifts Affecting Deaf Americans During the 20th Century

The 20th century witnessed significant societal transformations that profoundly impacted the lives of Deaf Americans, influencing their access to education, employment, and social inclusion. These shifts ranged from technological advancements to evolving attitudes towards disability.Several key societal changes played a role:

- Technological Advancements: Innovations like improved hearing aids and early forms of telecommunication devices began to emerge, offering new possibilities for communication, though their accessibility and effectiveness varied greatly throughout the century.

- Increased Advocacy and Civil Rights Movements: Inspired by broader civil rights movements, Deaf Americans became more vocal in demanding equal rights and opportunities. Organizations like the National Association of the Deaf (NAD), founded in 1880, grew in influence, advocating for policy changes and challenging discrimination.

- Shifting Perceptions of Disability: While prejudice persisted, there was a gradual, albeit slow, shift in societal attitudes away from viewing deafness solely as a deficit towards recognizing it as a cultural identity and a different way of experiencing the world. This was partly fueled by the growing visibility and advocacy of the Deaf community.

- Integration Efforts: Towards the latter half of the century, there was a move towards integrating Deaf students into mainstream educational settings, often with mixed results. This reflected a broader societal trend towards inclusion, but also raised concerns about the adequacy of support and the potential loss of Deaf community and culture.

Timeline of Major Legislative Changes Impacting Deaf Individuals in the US

Legislative changes have been instrumental in advancing the rights and ensuring the inclusion of Deaf individuals in the United States. These laws address various aspects of life, from education and accessibility to employment and communication.Here is a timeline of significant legislative milestones:

- Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973: This landmark legislation prohibited discrimination on the basis of disability in any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance. For Deaf individuals, this meant increased access to federally funded educational institutions, workplaces, and public services.

- The Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975 (now the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act – IDEA): This act mandated that all children with disabilities have access to a free and appropriate public education (FAPE) in the least restrictive environment (LRE). For Deaf students, this led to increased availability of specialized services, interpreters, and tailored educational plans.

- The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990: This comprehensive civil rights law prohibited discrimination based on disability in all areas of public life, including employment, transportation, public accommodations, and telecommunications. The ADA has been crucial in ensuring accessibility through provisions for auxiliary aids and services, such as sign language interpreters and closed captioning.

- The Telecommunications Act of 1996: This act included provisions aimed at increasing access to telecommunications for individuals with disabilities. It led to advancements in closed captioning, video description, and the development of telecommunications relay services (TRS), which allow Deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals to communicate with hearing individuals over telephone lines.

- The ADA Amendments Act of 2008 (ADAAA): This act clarified and expanded the definition of disability under the ADA, making it easier for individuals to establish that they have a disability and are protected by the law. This has been important in ensuring that the protections of the ADA are broadly applied to individuals with a wide range of conditions, including deafness.

Cultural and Social Aspects of Deaf History

The history of Deaf people in America is deeply intertwined with the development and evolution of their unique language, vibrant social structures, and the profound sense of cultural identity that binds them. Understanding these cultural and social dimensions offers crucial insights into the resilience, creativity, and community-building efforts of Deaf Americans throughout history.This section delves into the foundational elements of Deaf culture, exploring how language, social organizations, and regional variations have shaped the collective experience and individual identities within the American Deaf community.

Development and Cultural Significance of American Sign Language (ASL)

American Sign Language (ASL) is more than just a means of communication; it is the cornerstone of Deaf culture, a rich and complex visual-gestural language with its own grammar, syntax, and linguistic nuances. Its development in America is a fascinating story of cultural adaptation and linguistic innovation.The origins of ASL can be traced back to the early 19th century, with significant influences from Old French Sign Language brought to the United States by Laurent Clerc.

Clerc, a Deaf educator from France, co-founded the first permanent public school for the Deaf in North America, the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1817. Here, the indigenous sign languages used by American Deaf individuals began to merge with Clerc’s French Sign Language, leading to the formation of what we now recognize as ASL.

The cultural significance of ASL cannot be overstated:

- Identity Formation: For many Deaf individuals, ASL is intrinsically linked to their sense of self and belonging. It serves as a primary mode of expression and a powerful symbol of their cultural heritage.

- Community Cohesion: ASL facilitates deep connections and shared understanding within the Deaf community, fostering a strong sense of solidarity and mutual support.

- Artistic Expression: ASL is a dynamic language that lends itself to rich artistic forms, including poetry, storytelling, and theater, which are vital components of Deaf cultural expression.

- Educational Tool: The recognition and use of ASL in education have been crucial for the academic and social development of Deaf students, though this has been a site of historical struggle and advocacy.

The ongoing evolution of ASL, with regional dialects and the incorporation of new signs reflecting contemporary life, highlights its vitality as a living language.

Evolution of Deaf Social Organizations and Community Building

The establishment and growth of Deaf social organizations have played a pivotal role in fostering community, advocating for rights, and preserving Deaf culture in America. These organizations have served as vital hubs for social interaction, mutual aid, and collective action.Early Deaf social organizations often emerged organically from the schools for the Deaf, where students formed lifelong bonds. As Deaf individuals moved into broader society, the need for dedicated spaces and formal organizations became apparent.

These groups provided a sense of belonging and a platform for addressing shared concerns.

Key contributions of Deaf social organizations include:

- Social and Recreational Gatherings: Organizations facilitated social events, clubs, and recreational activities, providing opportunities for Deaf individuals to connect and build friendships outside of educational settings.

- Advocacy and Rights Protection: Many organizations became instrumental in advocating for the rights of Deaf people, campaigning against discriminatory practices in employment, education, and public services.

- Cultural Preservation: They served as custodians of Deaf culture, organizing events that celebrated ASL, Deaf history, and artistic traditions, thereby ensuring their transmission to future generations.

- Mutual Support Networks: These organizations often provided informal support systems, assisting members with challenges related to communication, employment, and daily life.

Examples of such organizations range from local social clubs to larger national bodies, each contributing to the robust social fabric of the Deaf community. The Gallaudet University Alumni Association, for instance, has historically been a significant force in advocating for Deaf education and professional opportunities.

Experiences of Different Deaf Communities Across US Regions

The Deaf experience in America is not monolithic; it varies significantly across different regions due to factors such as local demographics, historical settlement patterns, the presence of educational institutions, and the prevalence of specific industries. These regional differences have shaped distinct community characteristics and cultural expressions.In areas with a long history of Deaf education, such as the Northeast and Midwest, established Deaf communities often exhibit strong intergenerational connections and a deep-rooted understanding of Deaf history and ASL.

For example, communities around schools like the American School for the Deaf in Connecticut or the Ohio School for the Deaf have historically been centers for Deaf social life and cultural development.Conversely, in more recently established or geographically dispersed Deaf populations, community building might rely more heavily on technology and broader advocacy efforts. The emergence of Deaf communities in the Sun Belt states, for instance, may reflect patterns of migration and the establishment of new industries that provided employment opportunities for Deaf individuals.

Comparing and contrasting regional experiences reveals:

- Linguistic Variations: While ASL is the common language, regional dialects and variations in sign usage can exist, reflecting the historical development and influences within specific geographical areas.

- Social Networks: The density and nature of social networks can differ. Urban centers often have larger, more visible Deaf communities with a wider array of organizations, while rural areas might have smaller, more intimate networks where personal connections are paramount.

- Economic Opportunities: The types of industries prevalent in a region can influence the employment landscape for Deaf individuals, leading to different concentrations of Deaf professionals in fields like printing, manufacturing, or technology.

- Cultural Practices: While core Deaf cultural values are shared, regional traditions, specific social events, and the emphasis placed on certain cultural aspects might vary.

- Shared Experience and Understanding: The commonality of navigating a hearing-dominated world creates a powerful bond among Deaf individuals. This shared experience fosters empathy and mutual understanding that is central to belonging.

- Linguistic Empowerment: ASL serves as a primary vehicle for cultural expression and identity. Proficiency in ASL and participation in the Deaf community’s linguistic and social life are often central to a Deaf person’s sense of self.

- Cultural Norms and Values: Deaf culture has its own set of social norms, etiquette, and values, such as directness in communication, a strong emphasis on visual communication, and a deep respect for elders and history. Adherence to these norms reinforces identity and belonging.

- Community and Socialization: Deaf social organizations and gatherings provide essential spaces for socialization, where Deaf individuals can interact freely, form relationships, and experience a sense of community that is often lacking in the broader hearing society.

- Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet: Though hearing, Gallaudet played a pivotal role in establishing formal education for the Deaf in America. In 1817, he co-founded the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, with Laurent Clerc, a Deaf teacher from France. This marked a significant turning point, bringing systematic instruction to Deaf children.

- Laurent Clerc: A Deaf educator from France, Clerc was instrumental in the founding of the first permanent school for the Deaf in the United States. His pedagogical methods and his fluent command of Old French Sign Language significantly influenced the development of American Sign Language (ASL).

- Edward Miner Gallaudet: Son of Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, Edward Miner Gallaudet founded the National Deaf-Mute College (now Gallaudet University) in 1864. This institution became the world’s only liberal arts university for Deaf students, providing higher education opportunities previously unavailable.

- Harlan Lane: A prominent psychologist and author, Lane was a vocal critic of oralism and a champion of sign language. His research and writings, particularly “When the Mind Hears: A History of the Deaf,” brought critical attention to the suppression of sign language and the importance of Deaf culture.

- I. King Jordan: The first Deaf president of Gallaudet University, appointed in 1988, Jordan became a symbol of Deaf empowerment and self-determination. His presidency followed the “Deaf President Now” protest, a landmark event that asserted the Deaf community’s right to lead their own institutions.

- De’VIA (Deaf View/Image Art): This art movement, conceptualized by Deaf artists like Alex Abell and Betty Miller, explores themes of Deaf experience, culture, and identity. De’VIA artists use their art to express the world from a Deaf perspective, often incorporating elements of sign language and Deaf culture.

- Raymond Luczak: A prolific Deaf poet, writer, and filmmaker, Luczak has explored themes of identity, language, and the Deaf experience in his work. His poetry collections, such as “Eyes of the Dancing Men,” offer profound insights into Deaf life.

- Bernard Bragg: A pioneer in Deaf theater, Bragg was a celebrated actor, director, and mime artist. He co-founded the National Theatre of the Deaf (NTD) in 1967, a groundbreaking institution that provided professional theatrical performances in ASL and spoken English, bringing Deaf artistry to mainstream audiences.

- Marlee Matlin: An Academy Award-winning actress, Marlee Matlin is one of the most recognized Deaf figures in Hollywood. Her roles have brought visibility to Deaf actors and characters, advocating for authentic representation and challenging stereotypes.

- C.J. Jones: A renowned Deaf actor and advocate, Jones has a distinguished career in film, television, and theater. He has consistently championed the inclusion of Deaf talent and the use of ASL in media.

- Dr. Charles W. Boyer: A distinguished Deaf scientist and educator, Boyer has made significant contributions to the field of biology. He has advocated for STEM education for Deaf students and has been a role model for aspiring scientists.

- Dr. Michael J. Arndt: A Deaf physician and surgeon, Dr. Arndt has achieved excellence in his medical career. His success underscores the capability of Deaf individuals in demanding professional fields and highlights the importance of accessible medical education and practice.

- Lou Fant: A pioneer in Deaf education and a respected linguist, Fant was instrumental in the study and promotion of American Sign Language. His work provided a deeper understanding of ASL as a legitimate language, influencing educational practices and linguistic research.

- The National Association of the Deaf (NAD): Founded in 1880, the NAD is the leading civil rights organization for Deaf and hard-of-hearing Americans. It has been at the forefront of advocating for language rights, education, employment, and accessibility.

- The Deaf President Now movement: This student-led protest at Gallaudet University in 1988 was a watershed moment for Deaf rights. It successfully pressured the university board to appoint a Deaf president, demonstrating the power of collective action and self-determination.

- The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA): While not solely a Deaf advocacy initiative, the ADA, signed into law in 1990, has had a profound impact on accessibility for Deaf individuals. It mandates equal opportunity in employment, public services, public accommodations, and telecommunications.

- Advocates for Communication Access: Numerous individuals and organizations have championed the use of interpreters, captioning, and other assistive technologies to ensure communication access in all aspects of life, from education and healthcare to entertainment and public forums.

- Key Books:

- *A History of the Deaf in America* by John W. Gruener: A foundational text providing a broad overview of Deaf history from early settlement to modern times.

- *Deaf Heritage: A Lifeline to the Past* by Jack R. Gannon: This comprehensive work compiles personal narratives, historical accounts, and photographic evidence, offering a rich, multi-faceted view of Deaf life.

- *The Deaf Way: Perspectives from the World of Deaf Culture* edited by Harlan Lane: A collection of essays exploring various facets of Deaf culture and history, often with a focus on global perspectives but with significant American context.

- *Signing the Body Politic: Deaf Women’s Lives* edited by Brenda Jo Brueggemann: This anthology highlights the often-overlooked experiences and contributions of Deaf women in shaping American Deaf history and culture.

- Academic Journals:

- *Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education*: A premier journal publishing research on all aspects of Deafness, including historical and cultural studies.

- *Sign Language Studies*: This journal frequently features articles that delve into the historical development and societal impact of sign languages in America.

- *Disability & Society*: While broader in scope, this journal often includes articles that intersect with Deaf history, particularly concerning social inclusion, advocacy, and cultural identity.

- Notable Archival Collections:

- Gallaudet University Archives (Washington, D.C.): Home to an extensive collection of materials related to the history of deaf education, Gallaudet University, and the broader American Deaf community. This includes photographs, manuscripts, organizational records, and personal papers.

- National Association of the Deaf (NAD) Archives (Silver Spring, Maryland): The NAD archives house significant records of the organization’s advocacy efforts, legislative actions, and its role in shaping Deaf civil rights in America.

- American School for the Deaf Archives (West Hartford, Connecticut): As the first public school for the deaf in the United States, its archives provide invaluable insights into early deaf education and the lives of its students and educators.

- Relevant Historical Societies:

- The Deaf History Museum (online presence, associated with various organizations): While not a physical location in the traditional sense, many online initiatives curate and present historical artifacts and information.

- Local Historical Societies: Many regional and state historical societies may hold collections pertaining to deaf individuals or schools within their geographical area. Researching these can yield localized historical insights.

- Recommended Documentaries:

- *Sound and Fury* (2000): This Academy Award-nominated documentary explores the complex cultural and personal decisions faced by a Deaf family in rural America regarding cochlear implants for their children. It provides a poignant look at generational differences and cultural identity.

- *Through Deaf Eyes* (2006): A PBS documentary that traces the history of Deaf people in America, from the establishment of the first schools for the deaf to the present day, highlighting key figures and social movements.

- *Deaf President Now* (1990): This film documents the pivotal student protest at Gallaudet University in 1988, which led to the appointment of the first Deaf president. It is a critical event in Deaf civil rights history.

- Feature Films with Significant Deaf Representation:

- *Children of a Lesser God* (1986): While a fictional narrative, this film brought Deaf culture and sign language into mainstream consciousness and featured a powerful performance by Marlee Matlin, the first Deaf actress to win an Academy Award for Best Actress.

- *CODA* (2021): This Academy Award-winning film, while focusing on a hearing child of Deaf adults, offers a significant portrayal of Deaf family dynamics and culture, making it accessible and informative for a broad audience.

- Prominent Online Archives and Digital Projects:

- Gallaudet University Library Digital Archives: Many of Gallaudet’s archival materials are digitized and accessible online, including historical photographs, documents, and oral histories.

- Internet Archive (archive.org): This extensive digital library hosts a wide range of digitized books, films, and audio recordings, many of which are relevant to Deaf history. Searching for terms like “Deaf history,” “American School for the Deaf,” or “National Association of the Deaf” can yield valuable results.

- Deaf Cultural Digital Library: Various university libraries and Deaf advocacy organizations maintain digital collections that are often searchable and provide access to digitized historical documents, publications, and visual media.

- Websites of Deaf Advocacy Organizations: Organizations like the National Association of the Deaf (NAD) often have historical sections on their websites that provide timelines, key facts, and links to further resources.

- Handshapes: The specific form of the hand used in a sign.

- Movement: The way the hand moves through space.

- Location: Where the sign is made in relation to the body.

- Orientation: The direction the palm of the hand faces.

- Non-manual markers: Facial expressions, head tilts, and body shifts that convey grammatical information, tone, and emotion.

- Oralism: This approach emphasizes the use of spoken language and lip-reading for communication, advocating for the suppression of sign language in educational settings. Proponents believed that oral communication was essential for Deaf individuals to integrate into mainstream society. The International Congress on Education of the Deaf in Milan in 1880 was a turning point, where a resolution was passed endorsing oralism and leading to the widespread banning of sign language in many schools for the Deaf worldwide.

This had a devastating effect on Deaf education, often leading to isolation and reduced educational outcomes for students who struggled with spoken language acquisition.

- Manualism: This philosophy champions the use of sign language as the primary mode of communication and instruction for Deaf students. It recognizes sign language as a natural and effective language for Deaf individuals, fostering a strong sense of identity and community. Manualist educators and advocates believed that sign language provided a more accessible and comprehensive pathway to learning and cognitive development.

- Early Technologies: While not always specifically designed for the Deaf, early communication technologies indirectly impacted their lives. The invention of the telegraph and later the telephone, while primarily auditory, began to foster a more interconnected society.

- Telecommunications Devices for the Deaf (TDDs): The development of the TDD in the 1960s was a revolutionary step. This device allowed individuals to type messages that were transmitted over telephone lines, enabling Deaf individuals to communicate via text. TDDs were instrumental in breaking down communication barriers for personal and professional use.

- Video Relay Service (VRS): A significant leap in accessibility came with the advent of Video Relay Service (VRS). This service allows Deaf individuals to communicate with hearing individuals over the phone through a sign language interpreter who facilitates the conversation via video conferencing. VRS has greatly enhanced the ability of Deaf Americans to engage in everyday conversations and access essential services.

- Closed Captioning and Subtitling: The widespread adoption of closed captioning and subtitling in television, movies, and online videos has made visual media accessible to a much broader Deaf audience. This technology provides text-based transcriptions of audio content, allowing individuals to follow dialogue and understand the narrative.

- Modern Communication Tools: Today, a plethora of communication tools further enhance accessibility. Video conferencing platforms like Zoom and Skype, text messaging, email, and social media all provide visual means of communication. Specialized apps and devices continue to emerge, offering innovative solutions for real-time communication and information access.

- Bilingual-Bicultural Education: This approach recognizes ASL as the primary language of Deaf children and English as a second language, typically learned through reading and writing. It emphasizes the importance of Deaf culture and provides Deaf children with fluent ASL models and positive Deaf role models. This method aims to foster strong cognitive development and a robust sense of identity.

- Total Communication: A broader approach that aims to use any and all communication modes that are effective for a child. This can include spoken language, sign language (both ASL and Signed Exact English), lip-reading, gesturing, and finger spelling. The goal is to ensure that the child receives information in the most accessible way possible.

- Oral-Aural Approach: As discussed earlier, this method focuses exclusively on developing spoken language and lip-reading skills, often with the exclusion of sign language. While some individuals may achieve proficiency in spoken English, this approach has historically faced criticism for potentially hindering language development and cultural connection for many Deaf children.

- Intergenerational Transmission: A critical aspect of language maintenance is the intergenerational transmission of ASL. When Deaf children are born to hearing parents (the vast majority of Deaf children), they may not naturally acquire ASL unless actively exposed to it. Therefore, programs and initiatives that facilitate ASL learning for families and ensure exposure to fluent signers are vital for maintaining the language.

- Community-Based Learning: Many Deaf individuals learn and maintain ASL through immersion in the Deaf community itself. Social gatherings, cultural events, and informal interactions with other signers provide a natural and supportive environment for language acquisition and reinforcement.

- Public Demonstrations and Protests: Visual and impactful, these events have been used to draw public attention to issues such as inadequate educational services, lack of interpreters, and discriminatory practices. The Deaf President Now (DPN) protest at Gallaudet University in 1988 is a prime example, showcasing the power of collective action and unified demand.

- Lobbying and Political Engagement: Activists have actively engaged with policymakers at local, state, and federal levels to advocate for legislation and policies that protect and advance Deaf rights. This includes testifying at hearings, meeting with elected officials, and building coalitions.

- Legal Challenges: Filing lawsuits and participating in landmark court cases have been crucial in establishing legal precedents for accessibility and non-discrimination. These legal battles have often tested the interpretation and enforcement of existing laws.

- Public Awareness Campaigns: Through media appearances, educational initiatives, and community outreach, Deaf activists have worked to educate the broader public about Deaf culture, sign language, and the challenges faced by the community.

- Building Coalitions: Collaborating with other disability rights groups, civil rights organizations, and allies has strengthened the advocacy efforts, leveraging broader support and resources.

- National Association of the Deaf (NAD): Founded in 1880, the NAD is the world’s largest civil rights organization of, by, and for deaf and hard of hearing individuals. It has been a leading voice in advocating for civil, human, and educational rights for Deaf Americans for over a century.

- Gallaudet University: While primarily an educational institution, Gallaudet University has also served as a hub for activism and a symbol of Deaf empowerment. Its students and alumni have been deeply involved in advocacy efforts, most notably during the Deaf President Now protest.

- Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID): RID is a professional organization that sets standards for sign language interpreters and advocates for the availability of qualified interpreters, recognizing their crucial role in facilitating communication and access for Deaf individuals.

- American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities (ACCD): Though now defunct, the ACCD was a significant cross-disability advocacy organization that worked on broad civil rights issues affecting people with disabilities, including Deaf individuals, and played a role in the push for legislation like the ADA.

Understanding these regional nuances is crucial for a comprehensive appreciation of the diverse tapestry of Deaf life in America.

The Role of Deaf Culture in Shaping Identity and Belonging

Deaf culture plays an indispensable role in shaping the identity and fostering a profound sense of belonging for individuals who are Deaf. It provides a framework through which individuals understand themselves, their experiences, and their place in the world, often in contrast to societal perceptions of deafness.Deaf culture is not merely defined by the audiological condition of being deaf but by a shared language, values, traditions, and a collective history.

It offers a counter-narrative to the audist perspective, which often views deafness as a deficit. Instead, Deaf culture celebrates deafness as a difference and a source of unique cultural richness.

Deaf culture significantly influences identity and belonging through:

For many, identifying as “Deaf” (with a capital “D”) signifies not just the absence of hearing but an active participation in and identification with the Deaf community and its culture. This cultural affiliation provides a powerful source of pride, resilience, and a strong sense of belonging.

Notable Individuals and Their Contributions

The rich tapestry of Deaf history in America is woven with the impactful lives and dedicated efforts of numerous individuals. These pioneers, through their leadership, creativity, advocacy, and professional achievements, have profoundly shaped the experiences and rights of Deaf people. Understanding their stories offers invaluable insight into the evolution of Deaf culture and its place in American society.This section highlights some of the most influential figures, showcasing their diverse contributions across various fields.

Their legacies continue to inspire and inform ongoing efforts toward full inclusion and recognition.

Influential Deaf Leaders and Activists

Throughout American history, Deaf leaders have emerged as powerful voices advocating for the rights, education, and empowerment of the Deaf community. Their tireless work has been instrumental in challenging societal misconceptions and establishing essential services and institutions.

Key figures in Deaf leadership and activism include:

Achievements of Deaf Artists, Writers, and Performers

The creative spirit of the Deaf community has flourished through the exceptional talents of its artists, writers, and performers. These individuals have enriched American culture by sharing their unique perspectives and artistic expressions, often breaking barriers and challenging conventional notions of creativity.

Notable achievements in the arts include:

Scientists, Inventors, and Professionals with Significant Contributions

Despite facing unique challenges, Deaf individuals have made remarkable contributions to science, technology, and various professional fields. Their intellect, perseverance, and innovative thinking have led to significant advancements, demonstrating that hearing loss is not a barrier to intellectual and professional excellence.

Examples of Deaf professionals making impactful contributions include:

Advocates for Accessibility and Inclusion

The ongoing pursuit of accessibility and inclusion for Deaf individuals has been championed by passionate advocates who have worked tirelessly to break down communication barriers and foster a more equitable society. Their efforts have led to significant policy changes, technological advancements, and shifts in public perception.

Key advocates for accessibility and inclusion include:

Resources for Further Exploration

To deepen your understanding of Deaf history in America, a wealth of resources is available, spanning academic publications, archival materials, visual media, and digital platforms. Engaging with these diverse sources will provide a comprehensive and nuanced perspective on the rich tapestry of Deaf experiences and contributions throughout American history.This section is designed to guide you through some of the most valuable avenues for continued learning, offering both foundational knowledge and pathways to specialized research.

Reputable Books and Academic Journals

Exploring the scholarly literature is crucial for a thorough grasp of Deaf history. Books and journals offer in-depth analysis, primary source material, and the perspectives of leading historians and scholars in the field. These resources often present meticulously researched narratives that go beyond surface-level accounts.

Archival Collections and Historical Societies

Archival materials are the bedrock of historical research, offering direct access to primary documents, photographs, letters, and organizational records. Historical societies dedicated to Deaf history play a vital role in preserving these materials and making them accessible to researchers and the public.

Documentaries and Films Illuminating Deaf Experiences

Visual media offers a powerful and engaging way to connect with Deaf history and culture. Documentaries and films can bring historical events and personal stories to life, fostering empathy and understanding.

Online Archives and Digital Resources

The digital age has made a vast array of Deaf history resources more accessible than ever. Online archives and digital platforms provide convenient access to documents, images, and multimedia content, allowing for exploration from anywhere.

Language and Communication in Deaf History

The story of Deaf Americans is intrinsically linked to the evolution of language and communication. Understanding how Deaf individuals have communicated, how their languages have developed, and the societal forces that have shaped these processes is fundamental to grasping the richness and resilience of Deaf history. This section delves into the linguistic landscape of the Deaf community, exploring the development of American Sign Language, the historical debates surrounding educational methodologies, and the impact of technological advancements on communication accessibility.

American Sign Language: Historical Development and Linguistic Features

American Sign Language (ASL) is a vibrant, complex, and natural language with a history deeply intertwined with the Deaf community in the United States and Canada. Its origins can be traced back to the early 19th century, influenced by existing sign languages brought by immigrants, particularly from France. The establishment of the first public school for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1817 by Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet and Laurent Clerc was a pivotal moment, as Clerc brought with him French Sign Language (LSF), which significantly contributed to the formation of ASL.

ASL is a fully developed language, possessing its own unique grammar, syntax, and vocabulary, distinct from English. It is a visual-gestural language that utilizes handshapes, movements, facial expressions, and body posture to convey meaning. Its linguistic features include:

These elements work together to create a rich and nuanced communication system. For instance, the grammatical structure of ASL is not a direct translation of English; it often employs different word orders and uses spatial relationships to represent grammatical concepts like tense or plurality.

Oralism Versus Manualism in Deaf Education

The history of Deaf education in America has been marked by a significant and often contentious debate between two primary pedagogical philosophies: oralism and manualism. This dichotomy has profoundly impacted the communication methods available to Deaf individuals and the educational opportunities they have received.

The conflict between these two methods created a challenging environment for Deaf students, with many experiencing the frustration of not being fully understood or educated under oralist regimes. The resurgence and growing acceptance of ASL in recent decades have led to a more balanced approach in many educational settings, recognizing the benefits of bilingual-bicultural education.

Evolution of Communication Technologies and Accessibility

Technological advancements have played a crucial role in shaping the communication landscape for Deaf Americans, offering new avenues for connection and accessibility. From early innovations to modern digital tools, these technologies have continuously evolved to meet the needs of the Deaf community.

These technological developments have not only facilitated communication but have also empowered Deaf individuals by increasing their participation in all aspects of society.

Approaches to Language Acquisition and Maintenance within Deaf Communities

Within Deaf communities, diverse approaches to language acquisition and maintenance have historically existed and continue to evolve. These approaches are shaped by educational philosophies, societal attitudes towards sign language, and the inherent linguistic needs of Deaf individuals.

The ongoing dialogue and practice surrounding these approaches highlight the dynamic nature of language and its central role in the preservation and flourishing of Deaf culture.

Advocacy and the Fight for Rights

The journey of Deaf individuals in America has been profoundly shaped by their persistent advocacy and the ongoing fight for their rights. This struggle is not a singular event but a continuous thread woven through American history, often intersecting with broader civil rights movements and demanding systemic change. Understanding this aspect of Deaf history reveals the resilience and strategic brilliance of the Deaf community in asserting their inherent dignity and right to full participation in society.The pursuit of equal rights for Deaf Americans has involved a multifaceted approach, encompassing grassroots activism, legal challenges, and legislative reform.

These efforts have not only sought to address immediate discrimination but also to build a more inclusive and accessible future. The strategies employed have evolved over time, reflecting changing social and political landscapes, yet the core objective—full recognition and equitable treatment—has remained constant.

Intersection with Major Civil Rights Movements

The Deaf rights movement has frequently found common ground and shared strategies with other major civil rights movements in American history. The fight for racial equality, women’s suffrage, and the broader disability rights movement have all provided inspiration, legal frameworks, and tactical approaches for Deaf advocates. This intersectionality highlights the universal nature of the struggle for human rights and the power of solidarity.Deaf activists drew parallels between the discrimination they faced and the injustices experienced by other marginalized groups.

For instance, the concept of “separate but equal,” while ultimately dismantled for racial segregation, also had implications for educational and social segregation within the Deaf community. The language of rights, equality, and non-discrimination that emerged from the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s provided a powerful vocabulary and legal precedent for Deaf advocates to champion their own cause.

Tactics such as protests, boycotts, and legal challenges, successfully employed by other movements, were adapted and utilized by Deaf leaders to raise awareness and demand change.

Legislative Battles for Accessibility

A significant chapter in Deaf history is the long and arduous legislative journey to secure accessibility and protect the rights of Deaf individuals. These battles have been crucial in transforming public spaces, communication systems, and educational institutions to be more inclusive. The culmination of many of these efforts can be seen in landmark legislation that continues to shape the lives of Deaf Americans today.The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) of 1990 stands as a monumental achievement in this regard.

This comprehensive civil rights law prohibits discrimination based on disability and mandates accessibility in various sectors, including employment, public accommodations, transportation, and telecommunications. The ADA’s impact is far-reaching, requiring services like qualified interpreters, closed captioning, and accessible websites, thereby dismantling barriers that previously excluded Deaf individuals from full participation. Prior to the ADA, numerous smaller legislative victories and court cases chipped away at discriminatory practices, setting the stage for broader federal protections.

Strategies and Tactics of Deaf Activists

Deaf activists have employed a diverse range of strategies and tactics throughout history to advance their cause, demonstrating remarkable ingenuity and determination. These methods have ranged from direct action and public demonstration to sophisticated lobbying and legal advocacy. The effectiveness of these tactics has often been amplified by the unique cultural identity and communication strengths of the Deaf community.Notable strategies include:

Instrumental Organizations in Deaf Advocacy

Numerous organizations have played pivotal roles in championing the rights and well-being of Deaf Americans. These groups have served as vital platforms for advocacy, education, and community building, often leading the charge in legislative battles and public awareness campaigns. Their sustained efforts have been instrumental in achieving significant progress.Key organizations that have been at the forefront of Deaf advocacy include:

Visualizing Deaf History

To truly grasp the richness and complexity of Deaf history in America, visualization plays a crucial role. By imagining and describing visual representations of key moments, places, and people, we can bring this history to life, making it more accessible and impactful for a wider audience. These visual narratives allow us to connect with the past on a more emotional and intuitive level, fostering a deeper understanding and appreciation for the struggles and triumphs of the Deaf community.This section will explore descriptive narratives for potential illustrations that capture significant aspects of Deaf history, from the foundational educational institutions to the evolution of American Sign Language and the impact of pivotal legislative changes.

These descriptions are designed to serve as blueprints for visual storytelling, offering a glimpse into the lives and experiences that have shaped Deaf culture in America.

Early Deaf Schools and Their Students

Imagine a watercolor painting bathed in soft, natural light, depicting the entrance of the first American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, circa 1820. The building, a sturdy brick structure with tall, arched windows, stands proudly against a backdrop of rolling green hills. In the foreground, a diverse group of children, ranging in age from six to sixteen, are gathered.

Their faces, animated and expressive, convey a mix of curiosity and newfound confidence. Some are engaged in animated conversations using gestures, their hands forming graceful arcs and sharp angles. Others are clustered around a teacher, who is demonstrating a sign with patient encouragement. The atmosphere is one of discovery and community, a stark contrast to the isolation many of these children may have experienced before.

Another illustration could capture a bustling classroom inside such a school, with students diligently working at their desks, perhaps practicing penmanship or engaged in lessons illustrated with visual aids. The teacher, standing at the front, uses a combination of spoken words and signs, emphasizing the dual approach to education prevalent in these early institutions. The scene radiates a sense of hope and opportunity, marking the beginning of formal education for many Deaf Americans.

Key Historical Figures in Deaf Advocacy

Envision a striking portrait in oil, capturing Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet in his prime, perhaps in the 1830s. He is depicted with a thoughtful gaze, his brow furrowed slightly in concentration, his hand resting on an open book. The background might subtly suggest the early days of education, perhaps with a faint Artikel of a schoolhouse or a classroom setting. The portrait conveys his dedication and intellectual rigor in his pursuit of educating the Deaf.

Another visual could be a dynamic scene illustrating Laurent Clerc, the influential French Deaf educator, interacting with American students. He might be shown in a vibrant outdoor setting, perhaps on the grounds of the Hartford school, enthusiastically teaching signs. His posture is upright and commanding, yet his expression is warm and engaging, reflecting his passion for his work and his profound impact on the development of ASL in America.

A more modern representation might feature Helen Keller, not in a typical pose, but perhaps in a moment of profound connection with Anne Sullivan. Imagine a close-up shot, focusing on their intertwined hands, one conveying a word through touch, the other understanding it. The lighting could be dramatic, highlighting the intensity of their communication and the breakthrough of learning. This visual emphasizes the power of dedicated mentorship and the breaking of communication barriers.

The Evolution of American Sign Language (ASL)

Picture a series of interconnected panels, like a graphic novel, illustrating the journey of ASL. The first panel might depict a scene from the early 19th century, showing individuals communicating through a variety of gestural systems, some influenced by Indigenous sign languages and others by European signing. The signs are depicted as more rudimentary, yet clearly communicative. The next panel transitions to the mid-19th century, showing the influence of Clerc and the establishment of formal schools, with signs becoming more standardized and complex, hinting at the emergence of a distinct American Sign Language.

Subsequent panels would showcase the growing richness and grammatical sophistication of ASL, perhaps depicting classroom discussions, social gatherings, and even early forms of ASL storytelling. One panel could highlight the impact of the Milan Conference of 1880, visually representing the oralist movement’s suppression of sign language, with students shown being forced to speak and sign language being discouraged. The final panels would then illustrate the resurgence and celebration of ASL in the latter half of the 20th century, showcasing vibrant Deaf communities using ASL fluently, its recognition as a full-fledged language, and its integration into education and media.

The visual narrative would emphasize ASL’s dynamism, its adaptability, and its enduring cultural significance.

Impact of Legislative Changes on Deaf Americans’ Daily Lives

Imagine a split-screen visual. On one side, depict a scene from the pre-Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) era. A Deaf individual is attempting to access public services, such as a bank or a government office, but faces significant communication barriers. They are struggling to understand written information, and there are no interpreters available. Their expression conveys frustration and exclusion.

On the other side of the screen, show a similar scenario after the ADA’s implementation. The same individual is now interacting with a service provider, with a qualified ASL interpreter facilitating clear communication. The Deaf individual’s face shows relief and empowerment. The environment might also be depicted as more accessible, with visual alarms and TTY devices clearly visible. Another powerful illustration could depict the impact of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, showcasing a Deaf person successfully navigating a workplace where accommodations like interpreters or captioned videos are provided, leading to increased employment opportunities and professional growth.

The visual would emphasize the tangible improvements in accessibility, independence, and equality brought about by these legislative milestones.

Closure

In essence, exploring Deaf history in America is an enlightening endeavor that illuminates the strength, ingenuity, and cultural richness of the Deaf community. By engaging with the key events, notable individuals, and the ongoing advocacy for rights and accessibility, we gain a deeper appreciation for a vital part of the American story. The resources and insights shared provide a robust foundation for continued learning and a more comprehensive understanding of this significant heritage.