How to Tell a Simple Story in Sign Language sets the stage for this enthralling narrative, offering readers a glimpse into a story that is rich in detail and brimming with originality from the outset. This guide will illuminate the foundational principles of visual storytelling, from understanding narrative structure to mastering the nuances of facial expressions and body language. We will delve into the unique grammatical features of sign languages that enhance storytelling and explore practical methods for visually establishing characters and settings.

Embark on a journey to craft compelling narratives in sign language, beginning with the organization of a simple plot and progressing through the demonstration of clear visual cues for a beginning, middle, and end. You will learn to sequence signs logically, creating a narrative flow, and discover techniques for effective pacing and rhythm in your visual stories. The guide further emphasizes incorporating dynamic visual elements, such as spatial relationships, classifiers, repetition, and role-shifting, to elevate your storytelling and bring your narratives to life with vividness and clarity.

Understanding the Fundamentals of Simple Storytelling in Sign Language

Embarking on the journey of telling a simple story in sign language is an exciting endeavor that opens up a world of visual communication. Unlike spoken languages, sign languages rely on a rich tapestry of handshapes, movements, and non-manual signals to convey meaning and narrative. This section will guide you through the foundational principles that make visual storytelling effective and engaging.At its core, simple storytelling in sign language mirrors the universal principles of narrative structure found in spoken languages.

A story, regardless of its medium, typically involves a beginning, a middle, and an end. The beginning introduces characters and the setting, the middle develops the plot through a series of events and conflicts, and the end resolves the situation. In sign language, these elements are brought to life through a dynamic interplay of visual cues, making the narrative immersive and accessible.

Core Principles of Narrative Structure in Visual Languages

The essence of narrative structure in sign languages lies in its visual and spatial nature. Stories unfold not just sequentially in time, but also spatially, allowing for the representation of relationships between characters and objects, and the progression of events within a defined space. This spatial grammar is a cornerstone of effective sign language storytelling.Key elements of narrative structure in sign languages include:

- Establishing the Scene: The story begins by visually setting the stage. This involves introducing the environment or location where the story takes place, often through descriptive signs and spatial mapping.

- Introducing Characters: Characters are brought into existence through unique identifying signs or by assigning them a specific location in the signing space. Once introduced, they can be referred to by their identifier or by their assigned location.

- Plot Progression: Events unfold through a sequence of signs that depict actions, interactions, and changes. The flow of the narrative is guided by clear transitions between actions and by the use of temporal markers.

- Climax and Resolution: The story builds towards a peak of action or emotion, followed by a clear conclusion that resolves any conflicts or questions introduced earlier.

Importance of Facial Expressions and Body Language

Facial expressions and body language are not mere embellishments in sign language; they are integral grammatical components that carry significant meaning. They serve to convey emotion, attitude, grammatical information, and the intensity of an action. Without these non-manual signals, a signed story would feel flat and incomplete.Facial expressions and body language are crucial for:

- Conveying Emotion: A wide range of emotions, from joy and sadness to anger and surprise, are vividly expressed through specific facial configurations and body postures. For example, a furrowed brow and tightened lips can indicate frustration, while wide eyes and an open mouth might signal astonishment.

- Indicating Intent: The way a character moves their body and the subtle shifts in their facial expression can reveal their intentions or motivations. A sly smile might suggest mischievousness, while a determined set of the jaw could indicate resolve.

- Grammatical Functions: Certain facial expressions are used to mark questions, negations, or to indicate the role of a signer (e.g., acting as a narrator versus embodying a character). For instance, raised eyebrows often signal a yes/no question.

- Describing Size and Intensity: The size of a sign and the intensity of the movement can be amplified or diminished by body posture and facial cues, helping to describe the scale of an object or the force of an action.

Common Grammatical Features Unique to Sign Languages in Storytelling

Sign languages possess unique grammatical features that are highly effective for storytelling. These features allow for the efficient and expressive depiction of actions, relationships, and events in a visual and spatial manner.Some key grammatical features that enhance storytelling include:

- Spatial Referencing: Sign languages utilize the signing space to represent locations and relationships between characters and objects. A character introduced on the left side of the signing space can be referred to back to that position, maintaining continuity.

- Role Shifting: This is a powerful technique where the signer momentarily embodies different characters within the story. By shifting their body orientation, facial expression, and signing space, the storyteller can portray dialogue and actions from multiple perspectives.

- Classifiers: These are specific handshapes that represent categories of objects (e.g., vehicles, people, flat surfaces). When combined with movement, classifiers can depict how these objects move, interact, or are positioned in space, adding a dynamic visual element to the narrative.

- Non-Manual Markers (NMMs): As discussed, these are crucial. They include head nods/shakes, eye gaze, eyebrow movements, and mouth morphemes, all of which contribute grammatical information and emotional nuance to the story.

Examples of Establishing Characters and Settings Visually

The ability to establish characters and settings effectively is fundamental to drawing an audience into a signed story. This is achieved through a combination of specific signs and the strategic use of the signing space.Here are examples of how characters and settings can be established visually:

- Setting: To establish a forest setting, one might sign FOREST using a specific handshape and movement that evokes trees. Then, by signing the general area of the signing space and perhaps using a sweeping motion with open hands, the storyteller can indicate the expanse of the forest. Signs for sun, sky, or ground further enhance the visual representation of the environment.

- Character Introduction: A character can be introduced with a unique name sign, if they have one, or by signing their role (e.g., BOY, GIRL, OLD MAN). Once introduced, the character is assigned a specific location in the signing space. For instance, a BOY might be placed on the signer’s right, and a GIRL on the left.

- Referring to Characters: Subsequent references to the BOY would involve signing towards the right side of the signing space, and to the GIRL, towards the left. This spatial referencing eliminates the need to repeatedly sign their names or roles, creating a fluid narrative.

- Describing Character Appearance: Details about a character’s appearance, such as their height, clothing, or hair color, can be signed directly. For example, to show a TALL person, the signer might use a handshape to represent a person and move it upwards to indicate height.

Crafting a Basic Sign Language Narrative

Developing a simple story in sign language involves more than just stringing signs together; it requires a structured approach to create a narrative that is both understandable and engaging for the viewer. This section will guide you through organizing your thoughts into a coherent plot, utilizing visual cues to establish a clear beginning, middle, and end, and sequencing signs logically to propel your story forward.

We will also explore techniques to enhance the rhythm and pacing of your visual storytelling.Organizing a simple plot for a sign language story follows a fundamental narrative arc, ensuring a smooth flow of information and events. This structure helps the audience follow the progression of the story without getting lost.

Plot Organization for Simple Narratives

A well-organized plot is the backbone of any effective story. For sign language, this means visually establishing the scene, introducing characters and conflict, developing the action, and resolving the situation.A basic plot structure can be broken down into three key components: the beginning, the middle, and the end. Each part plays a crucial role in the overall comprehension and impact of the story.

Introducing Beginning, Middle, and End with Visual Cues

Distinct visual cues are essential for demarcating the different stages of a sign language narrative. These cues act as signposts for the audience, signaling transitions and helping them understand the story’s progression.

- Beginning: This section sets the scene and introduces the main characters or elements. Visual cues might include establishing the setting (e.g., signing ‘HOUSE’ then ‘OUTSIDE’), introducing characters with their unique classifiers or descriptive signs, and hinting at the initial situation or mood. For instance, a cheerful facial expression and upbeat signs can establish a positive beginning.

- Middle: This is where the plot develops, introducing conflict, challenges, or a sequence of events. Visual cues here can involve changes in facial expressions to reflect emotions like surprise, concern, or determination. The pace of signing might quicken to indicate action or slow down to emphasize a crucial moment. The introduction of new characters or objects can also signal the shift into the middle section.

- End: This part brings the story to a resolution. Visual cues for the end often involve a return to a more stable emotional state, a clear indication of the outcome (e.g., signing ‘HAPPY’ or ‘SAD’ to show the final feeling), and a concluding gesture or sign that signifies closure, such as a final nod or a sweeping hand movement indicating completion.

Sequencing Signs for Narrative Progression

The logical progression of signs is paramount in sign language storytelling. It ensures that the audience can follow the cause and effect of events and understand the narrative’s flow.Creating a sequence of signs that logically progresses a narrative involves careful consideration of temporal order, cause and effect, and thematic connections. This is achieved through a combination of sign choice, spatial arrangement, and non-manual markers.

- Establish Time and Place: Begin by establishing when and where the story takes place. Signs like ‘YESTERDAY’, ‘TOMORROW’, ‘MORNING’, ‘NIGHT’, ‘INSIDE’, ‘OUTSIDE’, or specific locations can be used.

- Introduce Characters and Objects: Clearly introduce the characters and any significant objects involved. Use appropriate classifiers or descriptive signs. For example, to introduce a person, you might sign ‘PERSON’ and then use a classifier to represent their movement or appearance.

- Show Action and Reaction: Depict actions and their immediate consequences. If a character does something, show what happens as a result. This can involve signing an action and then following it with a sign that indicates the outcome or reaction.

- Incorporate Dialogue and Thoughts: If characters are speaking or thinking, use appropriate techniques to represent this, such as role-shifting or using specific signs for ‘THINK’ or ‘SAY’.

- Build Towards a Climax: Gradually increase the intensity or complexity of the events leading to the story’s peak. This can be achieved through faster signing, more dynamic movements, and heightened emotional expressions.

- Provide a Resolution: Conclude the story by showing the outcome of the events and how the characters are affected. This should provide a sense of closure.

Techniques for Pacing and Rhythm in Visual Storytelling

Pacing and rhythm in sign language storytelling are achieved through the speed, duration, and variation of signs and movements. These elements create an engaging experience for the viewer, much like the tempo and flow of spoken language.Effective pacing and rhythm can significantly enhance the impact and clarity of a sign language story. They guide the viewer’s attention and emotional engagement.

- Speed of Signing: The speed at which signs are produced can dramatically alter the narrative’s feel. Faster signing can convey excitement, urgency, or action, while slower signing can emphasize important details, emotions, or moments of reflection. For example, a chase scene might be signed rapidly, whereas a moment of sadness would be signed more slowly and deliberately.

- Duration of Signs: Holding a sign for a slightly longer duration can give it more emphasis. This is particularly useful for highlighting key objects, emotions, or plot points. Conversely, quick, fleeting signs can represent passing events or minor details.

- Pauses and Silence: Strategic pauses are crucial for allowing the audience to process information and anticipate what comes next. They can also build suspense or create dramatic effect. The absence of signing, combined with appropriate facial expressions, can be very powerful.

- Repetition and Variation: Repeating a sign or a sequence of signs can reinforce an idea or create a rhythmic pattern. Varying the intensity or style of a repeated sign can also add nuance and interest.

- Non-Manual Markers (NMMs): Facial expressions, body shifts, and head movements are integral to pacing and rhythm. A furrowed brow and tense posture can slow down the pace and indicate tension, while a wide smile and open gestures can speed up the pace and convey joy.

- Use of Space: The way space is utilized to represent characters, objects, and locations can also contribute to the story’s rhythm. Moving through space with a deliberate, flowing motion can create a sense of continuity, while abrupt shifts can signal a change in scene or focus.

Incorporating Visual Elements for Enhanced Storytelling

Sign language is inherently visual, and mastering its visual nuances is key to crafting compelling and engaging stories. Beyond simply translating words, effective sign language storytelling leverages the space, the body, and the hands to create a rich and immersive experience for the audience. This section explores several techniques to enhance your narrative through these visual elements.

Spatial Relationships for Locations and Movements

The signing space is a dynamic canvas that can be utilized to establish and navigate locations, as well as depict the movement of objects or characters. By strategically assigning points in space, storytellers can create a clear mental map for their audience, making the narrative easier to follow and more vivid.To effectively use spatial relationships:

- Establish Locations: Designate specific points in your signing space to represent different places. For instance, the area to your left might be “home,” the center might be “the park,” and the right might be “the store.” Once established, consistently refer to these locations by signing in their designated areas.

- Depict Movement: Show movement by tracing paths within the signing space. A character walking from “home” to “the park” would be represented by a hand or body movement originating from the “home” location and moving towards the “park” location. The speed and style of the movement can convey the pace and manner of travel.

- Represent Distances: The distance between established locations in your signing space can also convey physical distance. A short movement between two points might represent a short walk, while a more expansive movement could indicate a longer journey.

- Show Interactions: When characters or objects interact, their relative positions in space are crucial. For example, if two characters meet, they would be signed in proximity to each other. If one character gives something to another, the movement of the object from one signing space to the other is vital.

Classifiers for Objects and Actions

Classifiers are a powerful tool in sign language for describing the appearance, size, shape, and movement of objects and beings. They are handshapes that represent a category of nouns and are then moved in space to depict their characteristics and actions, adding a layer of visual detail that written language often struggles to convey.Strategies for employing classifiers include:

- Describing Physical Attributes: Different handshapes represent different types of objects. For example, a flat hand (B-handshape) can represent a flat surface like a table or a book. This handshape can then be oriented and moved to show the object’s dimensions and placement. A bent-V handshape can represent a person or an animal, and its movement can describe how they walk or sit.

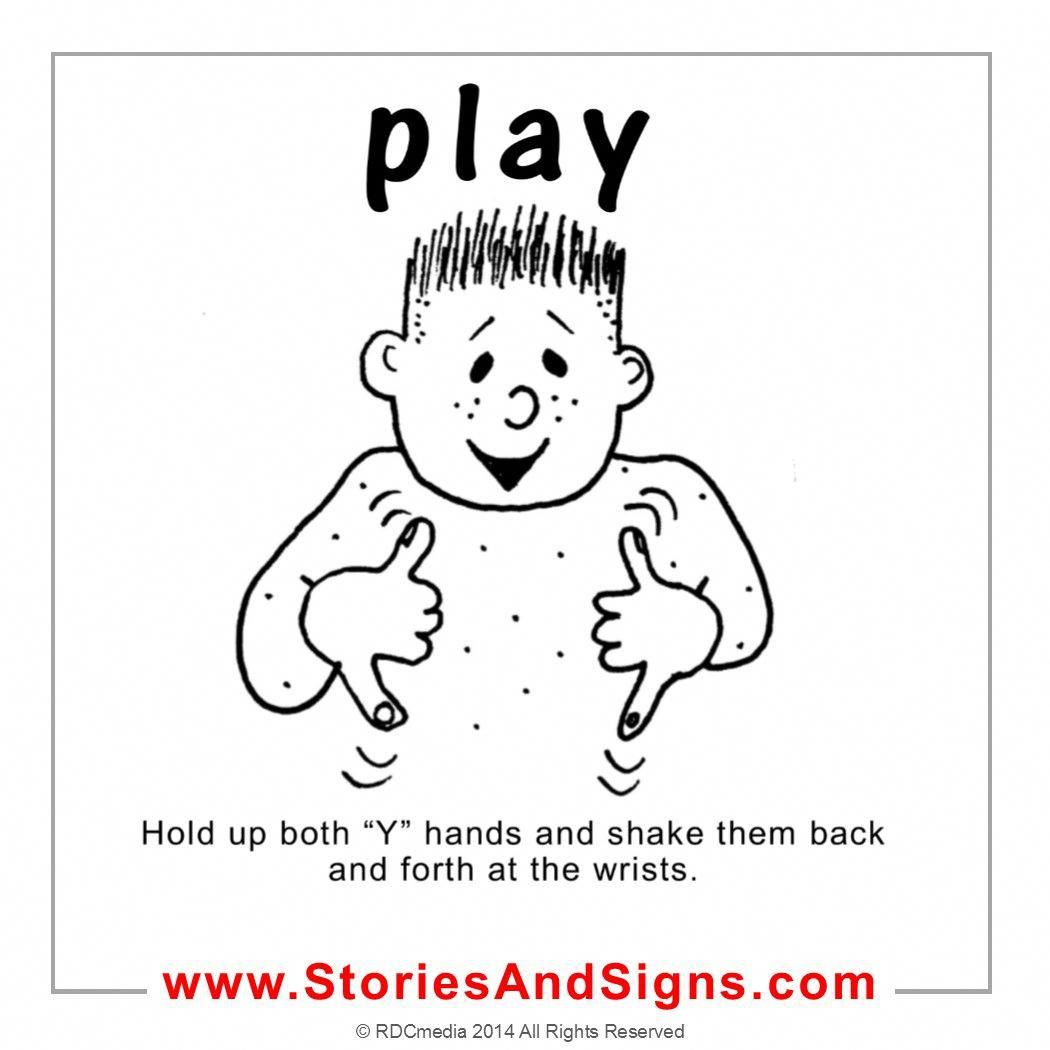

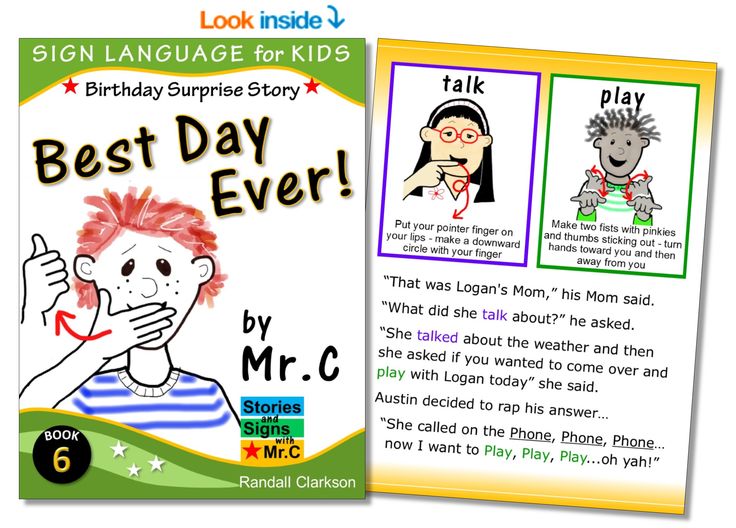

- Illustrating Actions: Classifiers are not just for static descriptions; they are essential for showing how things move and interact. For instance, using a classifier for a car (e.g., a Y-handshape representing wheels) and moving it along a path in the signing space clearly depicts the car driving. A classifier for a bird (e.g., a flat hand with the thumb extended) can be moved to show flight patterns.

- Showing Size and Shape: The size of the classifier handshape and the way it is manipulated can indicate the size and shape of the object. A large bent-V handshape moved slowly can depict a large, lumbering creature, while a small, quick bent-V handshape can show a small, agile one.

- Conveying Manner of Movement: The speed, direction, and trajectory of the classifier’s movement add nuance. A smooth, continuous movement might show an object gliding, while a jerky, stop-and-start movement could indicate something struggling or malfunctioning.

Repetition and Emphasis for Key Story Points

Just as in spoken language, repetition and variation in signing can draw attention to crucial elements of a story. These techniques help to reinforce important information, highlight emotional shifts, or signal significant plot developments.Methods for using repetition and emphasis include:

- Repeating a Sign: Signing a key word or phrase multiple times can emphasize its importance. For example, if a character is extremely scared, the sign for “FEAR” might be repeated with increasing intensity.

- Varying Sign Parameters: The speed, size, and intensity of a sign can be modified to create emphasis. A sign performed larger, faster, or with more forceful facial expression will naturally draw more attention than its standard execution.

- Facial Expressions and Body Language: These are powerful tools for emphasis. Exaggerated facial expressions, widened eyes, or a sudden change in posture can signal a critical moment or a strong emotion associated with a particular event.

- Pauses: Strategic pauses before or after a significant sign or event can build anticipation and highlight its importance. A dramatic pause before revealing a crucial piece of information can make that revelation much more impactful.

Role-Shifting for Portraying Different Characters

Role-shifting is a sophisticated storytelling technique that allows a single signer to embody multiple characters within a narrative. By shifting their body orientation, facial expressions, and signing style, the storyteller can seamlessly transition between characters, making it clear who is speaking or acting.To effectively use role-shifting:

- Establish Characters: Before dialogue or actions begin, clearly establish each character. This can be done by assigning each character a specific location in the signing space or by using distinct signing styles and facial expressions for each.

- Body Orientation: Shift your body to face a different direction to represent a different character. For example, if you are signing Character A’s dialogue, you might face forward. When you switch to Character B, you might turn slightly to the left or right. This creates a visual separation between the characters.

- Facial Expressions and Voice Quality: Each character should have a unique set of facial expressions and a distinct “voice” conveyed through their signing. A gruff character might have a stern expression and sign with more force, while a gentle character might have softer expressions and a lighter signing style.

- Signing Space Allocation: As mentioned earlier, different characters can be associated with different points in the signing space. When it’s a character’s turn to “speak,” you sign from their designated location.

- Transitions: Smooth transitions are key. A slight pause and a clear shift in body orientation and facial expression will signal to the audience that you are now embodying a different character.

Adapting Existing Stories for Sign Language

Translating a beloved story from spoken or written word into sign language is a rewarding endeavor that requires careful consideration and creative adaptation. This process goes beyond simple word-for-word translation, focusing instead on conveying the essence, emotion, and narrative flow in a visually rich medium. It’s about reimagining the story through the lens of visual-gestural communication.The core challenge lies in bridging the gap between auditory and visual languages.

Spoken language relies on sequential sounds and grammar, while sign language utilizes handshapes, movements, facial expressions, and body posture to convey meaning. Therefore, a direct translation can often feel clunky, unnatural, or even lose the intended message. Adapting a story involves a thoughtful transformation, ensuring the narrative remains engaging and accessible to a sign language audience.

Challenges and Considerations in Translating Spoken Narratives

When adapting a spoken narrative for sign language, several key challenges and considerations emerge. These involve understanding the fundamental differences between the two language modalities and how they impact storytelling.

- Grammatical Structures: Spoken languages have distinct grammatical rules, sentence structures, and verb conjugations that do not directly map to sign language. Sign languages have their own unique grammatical features, including the use of space, non-manual markers (facial expressions and body shifts), and topicalization.

- Idioms and Cultural References: Many expressions, idioms, and cultural references in spoken language are deeply tied to the auditory experience or specific cultural contexts that may not have direct visual equivalents. Finding appropriate sign language interpretations or culturally relevant alternatives is crucial.

- Pacing and Rhythm: The pacing and rhythm of spoken narration, including pauses, emphasis, and tone of voice, need to be translated into visual cues. This can involve varying the speed of signs, using specific non-manual markers, or employing spatial elements to indicate transitions or shifts in mood.

- Abstract Concepts: Conveying abstract ideas, emotions, or complex thoughts can be challenging. Sign language often uses established signs for abstract concepts, but in storytelling, these may need to be elaborated upon or illustrated through descriptive signing and visual metaphors.

- Character Voices: Differentiating characters in spoken narratives is often achieved through distinct vocal tones, accents, and speech patterns. In sign language, this is achieved through variations in signing style, speed, facial expressions, and body posture, which can be more nuanced and require careful planning.

Simplifying Complex Dialogue for Visual Communication

Complex dialogue in spoken stories often requires simplification to be effectively conveyed in sign language. The goal is to retain the core meaning and character intent without overwhelming the visual processing of the audience. This involves breaking down lengthy sentences, rephrasing abstract ideas, and using more direct visual representations.A framework for simplifying dialogue involves several steps:

- Identify Core Meaning: For each line of dialogue, determine the essential message the character is trying to convey. What is their intent, emotion, or factual statement?

- Condense and Rephrase: Long, convoluted sentences can be broken down into shorter, more direct statements. Complex vocabulary or jargon should be replaced with simpler, more commonly understood signs.

- Visualize Abstract Concepts: If dialogue involves abstract ideas, find ways to visually represent them. This might involve using established signs for emotions or concepts, or creating descriptive signs that paint a visual picture. For example, instead of signing “I feel a profound sense of unease,” one might sign “My stomach feels tight, I look around nervously.”

- Emphasize Non-Manual Markers: Facial expressions and body language are critical in sign language. Ensure that the emotions and attitudes conveyed through dialogue are clearly communicated through the signer’s non-manual markers. A sigh, a furrowed brow, or a slight head tilt can add significant depth.

- Consider Cultural Nuances: If the dialogue contains cultural references specific to the spoken language, find equivalent or analogous concepts that resonate with a sign language audience. This might involve substituting a specific cultural practice with a more universally understood action.

Essential Plot Points for Sign Language Adaptation

When adapting a story for sign language, it is paramount to identify and retain the essential plot points. These are the narrative anchors that drive the story forward and ensure the audience can follow the sequence of events. The focus should be on the “what” and “why” of the story, ensuring clarity and coherence in the visual narrative.The following elements are crucial to preserve:

- Inciting Incident: The event that kicks off the main conflict or journey of the protagonist.

- Rising Action: Key events that build tension and lead to the climax. This includes significant challenges, discoveries, or character developments.

- Climax: The peak of the story’s conflict, where the protagonist confronts the main obstacle.

- Falling Action: The events that occur after the climax, leading to the resolution.

- Resolution: The outcome of the story, where loose ends are tied up.

- Character Motivations: The underlying reasons for characters’ actions are vital for understanding their choices and the overall narrative.

- Key Relationships: The dynamics between important characters and how they evolve throughout the story.

Techniques for Maintaining the Spirit and Message of the Original Story

Preserving the original spirit and message of a story in its sign language adaptation requires a deep understanding of the source material and a creative approach to visual storytelling. It’s about capturing the emotional resonance, thematic depth, and overall intent of the original work.Effective techniques include:

- Embrace Visual Metaphors: Sign language is inherently visual. Use established signs or create new visual metaphors that evoke the same feelings or ideas as the original text. For instance, a feeling of oppression might be represented by a signer being visually “weighed down” by their hands.

- Focus on Emotional Expression: Facial expressions and body language are powerful tools in sign language. Amplify the emotional cues present in the original story through nuanced and expressive signing. A subtle shift in eyebrow position or a change in posture can convey a wealth of emotion.

- Utilize Spatial Storytelling: Sign languages often use the signing space to represent locations, characters, and relationships. This can be a powerful tool for illustrating the setting of the story, the movement of characters, and the interactions between them.

- Maintain Character Voice through Signing Style: While direct vocal imitation is not possible, the personality and demeanor of characters can be conveyed through their signing style. A boisterous character might sign with large, energetic movements, while a timid character might sign with smaller, more hesitant gestures.

- Strategic Use of Repetition and Emphasis: Just as spoken language uses repetition and emphasis to highlight key ideas, sign language can employ these techniques visually. Repeating a sign with increased intensity or holding a specific handshape can draw attention to important elements of the story.

- Incorporate Iconic Signs: Where possible, utilize signs that are iconic or visually descriptive of the concept they represent. This can make the narrative more intuitive and engaging for the audience. For example, the sign for “walk” often visually mimics the action of walking.

Practice and Refinement of Sign Language Stories

Mastering the art of sign language storytelling involves dedicated practice and a commitment to continuous improvement. This section Artikels effective strategies for honing your skills, from establishing a consistent practice routine to actively seeking and incorporating feedback. Through focused exercises and self-assessment, you can significantly enhance the clarity, fluency, and impact of your sign language narratives.

Organizing a Practice Routine for Improved Fluency and Clarity

A structured practice routine is essential for developing the muscle memory, speed, and expressiveness required for fluent sign language storytelling. Consistent engagement with the language allows for the internalization of signs, grammatical structures, and the nuances of visual communication.To build a robust practice routine, consider the following elements:

- Daily Sign Practice: Dedicate at least 15-30 minutes each day to practicing individual signs and short phrases. Focus on the correct handshape, location, movement, and orientation.

- Story Rehearsal: Rehearse your prepared stories multiple times. Pay attention to the flow between signs, the pacing of your narrative, and the clarity of your expressions.

- Mirror Practice: Utilize a mirror to observe your signing. This allows you to identify any inconsistencies in your handshapes or movements and to refine your facial expressions and body language.

- Recording and Review: Regularly record yourself signing and review the footage. This objective perspective is invaluable for spotting areas that need improvement.

- Varying Content: Practice telling different types of stories, from simple anecdotes to more complex narratives, to broaden your signing repertoire and adaptability.

Developing a Vocabulary of Descriptive Signs

A rich vocabulary of descriptive signs is crucial for bringing a story to life. These signs go beyond basic vocabulary to convey emotions, textures, sizes, shapes, and actions in a vivid and engaging manner. Building this specialized vocabulary requires intentional effort and creative exploration.Exercises to expand your descriptive sign vocabulary include:

- Sensory Exploration: Focus on describing sensory experiences. For example, practice signs for different textures (smooth, rough, sticky), temperatures (hot, cold, warm), sounds (loud, quiet, soft), and tastes (sweet, sour, bitter).

- Action Verbs: Expand your collection of action verbs. Instead of just “walk,” explore signs for “stroll,” “march,” “tiptoe,” “dash,” or “lumber.”

- Emotional Expression: Practice a wide range of facial expressions and body movements to convey emotions like joy, sadness, anger, surprise, fear, and curiosity.

- Figurative Language: Learn and practice signs that represent metaphors, similes, and other figurative language devices commonly used in storytelling.

- Environmental Details: Develop signs to describe settings, such as different types of weather, landscapes, or interior environments.

Receiving and Providing Constructive Feedback on Sign Language Narratives

Feedback is a powerful tool for growth in sign language storytelling. Both receiving feedback gracefully and offering it thoughtfully contribute to a more supportive and effective learning environment. Constructive criticism, when delivered and received with an open mind, can highlight blind spots and offer new perspectives.Methods for engaging in feedback:

- Seek Out Feedback Partners: Connect with other sign language learners or fluent signers who are willing to offer their insights.

- Prepare Specific Questions: When seeking feedback, ask targeted questions about aspects of your storytelling you are unsure about, such as clarity of a specific sign, the effectiveness of your facial expressions, or the overall pacing.

- Listen Actively and Without Defensiveness: When receiving feedback, focus on understanding the points being made rather than immediately justifying your choices.

- Summarize and Clarify: After receiving feedback, briefly summarize what you heard to ensure you have understood correctly. Ask clarifying questions if needed.

- Offer Specific and Actionable Feedback: When providing feedback to others, be specific about what you observed and suggest concrete ways they can improve. Frame your comments positively and constructively.

- Focus on Strengths as Well: Always acknowledge the positive aspects of a narrative before offering suggestions for improvement.

Methods for Recording and Reviewing One’s Own Sign Language Storytelling

Self-assessment through recording and review is an indispensable part of refining your sign language stories. This process allows for an objective evaluation of your performance, enabling you to identify strengths and weaknesses that might otherwise go unnoticed.Effective methods for recording and review include:

- Video Recording: Use a smartphone, webcam, or digital camera to record yourself signing your stories. Ensure the camera angle captures your entire upper body and face clearly.

- Focus on Specific Elements: During review, pay close attention to:

- Sign Clarity: Are your signs recognizable and correctly formed?

- Facial Expressions: Do your expressions match the tone and content of the story?

- Body Language: Is your posture and movement contributing to the narrative?

- Pacing and Flow: Is the story easy to follow, or are there awkward pauses or rushed sections?

- Grammar and Syntax: Are you using appropriate sign language grammar?

- Audio Recording (Optional but Recommended): If you are using voice-over or have a spoken component to your storytelling, record the audio simultaneously to check for synchronization.

- Regular Review Schedule: Set aside dedicated time after each practice session to review your recordings.

- Note-Taking: Keep a journal or document where you record your observations, areas for improvement, and specific goals for your next practice session.

Last Recap

In essence, this exploration into How to Tell a Simple Story in Sign Language provides a comprehensive toolkit for aspiring storytellers. We have covered the fundamental building blocks, the art of crafting a narrative, the power of visual elements, the considerations for adapting existing stories, and the crucial steps for practice and refinement. By mastering these techniques, you are well-equipped to share captivating stories that resonate with audiences through the beautiful and expressive medium of sign language.