As How to Think in Sign Language, Not Just English takes center stage, this opening passage beckons readers into a world crafted with good knowledge, ensuring a reading experience that is both absorbing and distinctly original. This exploration delves into the fascinating cognitive shift required to move beyond English-centric thought patterns and embrace a truly visual-gestural way of conceptualizing ideas.

We will uncover the fundamental differences in grammar and thought processes, offering practical strategies to bridge the gap and cultivate a deeper understanding of sign language as a language of thought, not merely a translation of spoken words.

Understanding the core concept of thinking in sign language involves recognizing that it is a fundamentally different way of processing information. Unlike spoken languages, which are linear and sequential, sign languages utilize spatial grammar, facial expressions, and body language to convey complex meanings simultaneously. This Artikel will guide you through the nuances of this visual-gestural approach, highlighting common misconceptions and demonstrating how to begin shifting your own cognitive framework.

Understanding the Core Concept: Thinking in Sign Language

Moving beyond simply translating English words into signs, truly thinking in sign language involves a fundamental shift in cognitive processing. It’s about engaging with language in a visual-gestural modality, where meaning is constructed through a complex interplay of handshapes, movements, facial expressions, and body posture, all within a spatial framework. This approach leverages the inherent characteristics of sign languages, which differ significantly from the linear, auditory-sequential nature of spoken languages like English.

Embracing this conceptual shift opens up new avenues for understanding communication, cognition, and the diverse ways humans make meaning.The primary distinction lies in how information is encoded and processed. Spoken languages, like English, are linear and sequential. We produce sounds one after another, and meaning is derived from the order of these sounds and the words they form. In contrast, sign languages are inherently spatial and simultaneously convey multiple pieces of information.

A single sign can incorporate semantic meaning, grammatical markers, and even emotional tone, all expressed through a combination of visual elements. This allows for a more holistic and integrated way of conceptualizing and expressing thoughts.

Grammatical Structures in Sign Languages vs. English

The grammatical structures of sign languages are a departure from English sentence construction, influencing how users organize and convey information. English relies heavily on word order, prepositions, and auxiliary verbs to establish relationships between words and convey grammatical information. Sign languages, however, utilize a rich array of non-manual markers (facial expressions, head tilts, body shifts) and spatial grammar to convey these same grammatical functions.For instance, in English, we might say, “The book is on the table.” To express possession, we use “my book.” In American Sign Language (ASL), the concept of “on” can be shown by placing the sign for BOOK in a specific location in space, and then placing the sign for TABLE in another location, with the BOOK sign positioned above the TABLE sign.

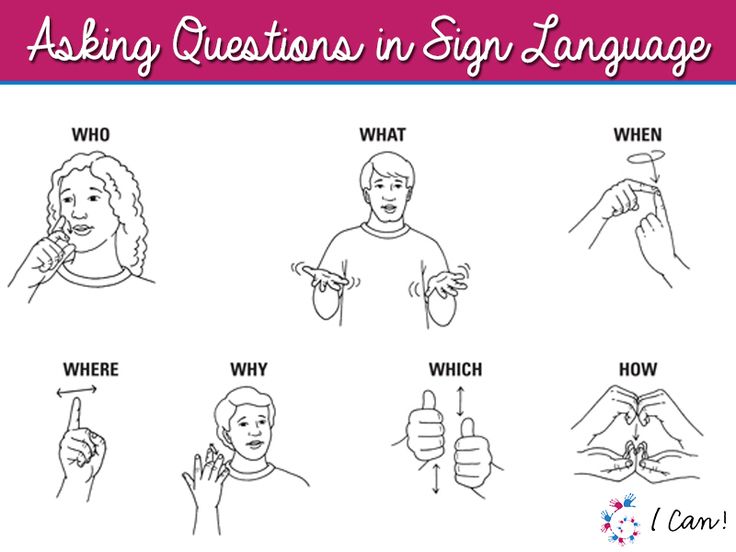

Possession can be indicated by a simple possessive sign or by establishing a location in space for “my” and then placing the “book” in that designated area. Furthermore, questions in English often involve changes in intonation or the addition of question words. In ASL, a yes/no question is typically marked by raised eyebrows and a slight forward head tilt, while wh-questions (who, what, where, when, why) are marked by furrowed brows.

Spatial Grammar and Thought Processes

Spatial grammar is a cornerstone of sign languages, profoundly influencing how users conceptualize and organize information. This means that the physical space in front of the signer becomes a crucial element for conveying meaning, establishing referents, and depicting relationships between entities. This visual-spatial organization allows for a more direct and concrete representation of concepts.Consider the representation of movement or direction.

In English, we use verbs and adverbs: “He walked to the store,” “She ran quickly.” In a sign language, the movement path of a sign can directly depict the direction and manner of movement. For example, the sign for “walk” can be modified by changing the direction of the hand movement to indicate “walked to the store.” Similarly, abstract concepts can be grounded in space.

Time, for instance, is often mapped onto a timeline in space, with the past typically located behind the signer and the future in front. This spatial mapping can lead to a more intuitive understanding of temporal relationships.

Common Misconceptions About Thinking in Sign Language

Several common misconceptions surround the idea of “thinking in sign language.” One prevalent misunderstanding is that sign language is simply a gestural form of a spoken language, or a pantomime. This is inaccurate; sign languages are fully developed, natural languages with their own unique vocabularies, grammars, and linguistic structures, independent of any spoken language.Another misconception is that sign language users think in English and then translate it into signs.

While some bilingual signers may engage in code-switching or translation, for native or highly fluent signers, thoughts often arise directly in the visual-gestural modality. This means that their internal monologue or conceptualization process is already framed within the grammatical and semantic structures of sign language, rather than being an English thought that is then converted. It’s akin to a native English speaker not consciously translating their thoughts from, say, French to English; their thoughts are already in English.

This direct conceptualization in sign language can lead to a different way of processing information and experiencing the world.

Bridging the Gap: From English to Sign Language Conceptualization

Transitioning from thinking in English to thinking in sign language involves a fundamental shift in how we perceive and organize information. It’s not simply about finding the right signs for English words, but rather about grasping the underlying concepts and expressing them visually. This section will explore practical strategies to facilitate this cognitive shift, enabling a more fluid and intuitive approach to sign language communication.Moving from a linear, word-based language like English to a spatial and visual language like sign language requires a conscious effort to deconstruct and reconstruct our thoughts.

This process involves understanding how sign languages encode meaning differently and developing techniques to translate abstract English ideas into concrete visual representations.

Translating English Sentence Structures into Sign Language Thought Patterns

English sentence structure often follows a Subject-Verb-Object (SVO) pattern. Sign languages, however, have more flexible structures that prioritize topicalization and visual information. Understanding these differences is key to effective translation. For instance, in English, we might say, “I am going to the store tomorrow.” In sign language, the concept might be more effectively conveyed by establishing the topic (store), then the action (go), and finally the time (tomorrow), often with a facial expression indicating future intent.This involves several strategic approaches:

- Topicalization: Place the most important information at the beginning of the sentence. For example, instead of “The book is on the table,” one might sign TABLE BOOK ON.

- Topic-Comment Structure: Sign the topic first, then provide a comment about it. This allows for a more natural flow in sign language.

- Omission of Redundant Words: Sign languages often omit articles (a, an, the), prepositions, and auxiliary verbs that are implied by context or the visual nature of the signs.

- Verb Agreement and Directionality: Many sign language verbs are directional, meaning the movement of the sign indicates the subject and object. This inherently encodes grammatical information that would require separate words in English.

Breaking Down Complex English Ideas into Core Visual Components

Complex English ideas often rely on abstract nouns and intricate verb phrases. To translate these into sign language, we must identify the essential visual elements and actions that represent the core meaning. This involves analyzing the essence of the idea and finding the most direct and visually comprehensible way to convey it.Methods for achieving this include:

- Decomposition: Break down lengthy English phrases into their fundamental concepts. For example, “The rapid advancement of technology” could be broken down into concepts like FAST, TECHNOLOGY, CHANGE, UP.

- Visual Metaphors: Sign languages frequently employ visual metaphors. For instance, “thinking” might be represented by a sign pointing to the forehead, symbolizing the location of thought.

- Spatial Relationships: Utilize the signing space to represent physical locations, relationships between objects, and the movement of entities. This is a cornerstone of sign language conceptualization.

- Sequencing of Actions: For processes or narratives, the order in which signs are presented is crucial. Each sign represents a step or a component of the overall idea.

The Role of Classifiers in Representing Objects and Actions Conceptually

Classifiers are a vital grammatical feature in sign languages that allow for the conceptual representation of objects and actions. They are handshapes that describe the properties of a noun (e.g., its shape, size, number of legs) and are then used to depict movement, location, and interaction.Classifiers function in several key ways:

- Describing Attributes: A specific handshape can represent a flat object, a cylindrical object, a person, or a vehicle, conveying its basic form.

- Depicting Movement and Location: Once a classifier is established, it can be moved through the signing space to show how an object moves or where it is situated. For example, a classifier for a car can be moved to show it driving down a road.

- Illustrating Interactions: Classifiers can interact with each other to show how objects or people engage. Two person classifiers, for instance, could be used to show them talking or shaking hands.

- Showing Quantity: Multiple instances of a classifier can be used to represent a group of objects or people.

For example, to describe a car driving on a road, one might use a “vehicle classifier” (often a flat hand or a “V” handshape with fingers spread) to represent the car, and then move this classifier along a line established in the signing space to represent the road. This visual narrative bypasses the need for separate English words like “car,” “drive,” and “on.”

Practicing the Shift from an English-Centric Mental Model to a Sign Language One

Cultivating a sign language-centric mental model requires consistent practice and a willingness to embrace a different way of thinking. It’s an ongoing process of observation, imitation, and active engagement with the language.Effective practice methods include:

- Immersion: Regularly interact with native signers and immerse yourself in the visual and spatial aspects of the language.

- Visual Storytelling: Practice describing everyday events and abstract concepts using only signs and visual cues, without relying on English translation.

- Analyzing Visual Information: Pay close attention to how information is presented visually in sign language, including facial expressions, body language, and the use of space.

- Deconstructing English Sentences Visually: Take an English sentence and try to visualize its core components and actions, then translate that visualization into signs.

- Using Glossing (with caution): While not a direct translation, understanding sign language glossing can help identify the core signs and their order, aiding in the conceptual breakdown.

For instance, when you see a dog run across a park in English, you might think “dog ran park.” In sign language, you would first establish the dog (perhaps with a classifier for an animal), then show its movement (running) through space, and indicate the location (park). This involves a direct visual mapping rather than a word-for-word substitution.

Developing Visual-Gestural Fluency

Moving beyond simply understanding the vocabulary of sign language, true fluency involves mastering the visual and gestural aspects that form its very essence. This section focuses on cultivating the skills necessary to not only produce signs accurately but also to imbue them with the expressiveness and nuance that characterize natural communication in sign language. It’s about transforming the physical act of signing into a rich and meaningful form of expression.Developing visual-gestural fluency is a continuous journey that requires dedicated practice and a deep engagement with the modality.

It involves training your eyes to observe and recall visual information with precision, and your body to articulate signs with clarity and fluidity. This section provides practical strategies and exercises to help you build this essential skill set.

Organizing a Practice Routine for Visual Recall and Gestural Articulation

A structured practice routine is crucial for enhancing visual memory and refining the physical execution of signs. Consistency and targeted exercises are key to building the muscle memory and cognitive pathways necessary for fluid signing.To establish an effective practice routine, consider incorporating the following elements:

- Daily Sign Review: Dedicate 15-20 minutes each day to reviewing signs learned previously. This can involve using flashcards, apps, or even self-recorded videos. Focus on both the handshape and movement.

- Movement Drills: Isolate specific movements common in sign language (e.g., circular motions, up-and-down movements, outward extensions). Practice these movements repeatedly without specific signs to build muscle memory and control.

- Handshape Mastery: Practice forming each handshape accurately and consistently. Use a mirror to check your handshapes and compare them to reference materials.

- Speed and Clarity Exercises: Gradually increase the speed at which you produce signs while maintaining clarity and accuracy. Start with individual signs and then progress to short phrases.

- Varied Practice Methods: Alternate between different practice methods to keep your routine engaging and to target different learning styles. This might include using online resources, working with a tutor, or practicing with peers.

Encouraging the Use of Facial Expressions and Body Language

Sign language is a full-body communication system, and facial expressions and body language are integral to conveying meaning, emotion, and grammatical information. Relying solely on handshapes will result in a flat and incomplete form of communication.Exercises to integrate non-manual markers effectively include:

- Emotion Mirroring: Practice signing common phrases while consciously displaying the corresponding emotion on your face. For example, sign “happy” with a genuine smile and “sad” with a downturned expression.

- Grammatical Non-Manual Markers: Focus on specific facial expressions that indicate grammatical functions. For instance, raised eyebrows often signify a yes/no question, while a furrowed brow can indicate a WH-question (who, what, where, etc.). Practice signing questions with the appropriate facial cues.

- Body Shift and Posture: Experiment with how body shifts and posture can differentiate between subjects or topics in a sentence. For example, when referring to two different people, you might shift your body slightly to represent each person.

- Role Shifting: Practice embodying different characters or perspectives within a narrative by altering your facial expressions, body posture, and even the way you move your head and shoulders.

- Observational Analysis: Watch videos of fluent signers and pay close attention to their non-manual markers. Try to mimic their expressions and body language as you practice signing the same content.

Developing Mental Imagery Aligned with Sign Language Syntax

Sign language syntax often differs significantly from English, relying on spatial relationships and visual metaphors. Developing mental imagery that aligns with this visual-gestural structure is crucial for thinking in sign language.Techniques for cultivating this visual-spatial thinking include:

- Spatial Mapping: Visualize a space in front of you as a canvas where you can place concepts and characters. Use this space to represent relationships, directions, and the flow of information. For example, when signing about two people interacting, mentally place them in distinct locations within your signing space.

- Conceptual Visualization: Before signing a concept, create a vivid mental image of it. For instance, to sign “tree,” visualize a tree with its trunk, branches, and leaves. Then, translate that visual into the appropriate sign.

- Directionality and Movement: Understand how the direction and movement of signs convey meaning. Practice visualizing the path of a sign and how it relates to other elements in the sentence. For example, the sign for “give” can change its meaning based on the direction it moves from the giver to the receiver.

- Metaphorical Thinking: Sign language often uses visual metaphors. Practice translating abstract concepts into concrete visual representations. For example, “understanding” might be visualized as light bulbs turning on, which is then translated into the sign.

- Storyboarding: For longer narratives or explanations, mentally (or physically) storyboard the sequence of events, visualizing the spatial arrangement and the flow of actions. This helps in structuring your signing logically according to sign language grammar.

The Importance of Immersion and Interaction with Sign Language Communities

Immersion and consistent interaction with native signers and the Deaf community are paramount for developing true conceptual understanding and fluency in sign language. This is where theoretical knowledge transforms into practical, nuanced communication.The benefits of immersion and interaction are manifold:

- Natural Language Acquisition: Observing and interacting with fluent signers provides exposure to the natural rhythm, flow, and idiomatic expressions of the language that cannot be fully replicated through textbooks or apps.

- Contextual Understanding: Sign language is deeply embedded in culture. Immersion allows for an understanding of the cultural context, social norms, and communication styles that influence how the language is used.

- Feedback and Correction: Direct interaction provides invaluable opportunities for feedback and correction from experienced signers, helping to refine accuracy in both manual and non-manual aspects of signing.

- Development of Signer’s Perspective: Engaging with the Deaf community helps in adopting the “signer’s perspective,” where communication is naturally conceived and expressed through a visual-gestural lens, rather than trying to translate from an English mindset.

- Building Confidence and Fluency: Regular communication in real-world scenarios builds confidence and accelerates the development of fluency, making signing a more automatic and integrated part of one’s communication repertoire.

“To truly think in sign language, one must embrace its visual nature and allow the world to be perceived and expressed through movement and space.”

Practical Applications and Benefits

Thinking in sign language transcends mere translation; it represents a fundamental shift in cognitive processing with profound implications for communication, learning, and creativity. This section explores the tangible advantages of adopting a visual-gestural conceptual framework, benefiting both sign language users and those who engage with it.

Embracing a sign language-centric thought process offers a wealth of benefits, enhancing communication for deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals by providing a more direct and intuitive mode of expression. Furthermore, it unlocks significant advantages for hearing individuals learning sign language, fostering deeper understanding and more effective interaction. The cognitive enrichment derived from multilingualism, particularly when including sign languages, is substantial, impacting areas such as problem-solving and creative thinking.

Enhanced Communication for Deaf and Hard-of-Hearing Individuals

For individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing, thinking directly in sign language means bypassing the intermediary step of mentally translating spoken language into signs. This direct approach leads to more fluid, nuanced, and immediate communication. It allows for the natural expression of complex thoughts and emotions, leveraging the full visual-gestural capacity of sign languages, which often incorporate facial expressions, body language, and spatial grammar that are integral to meaning.

Consider the concept of describing a complex event. In spoken English, one might describe the sequence of actions verbally. In sign language, a signer can simultaneously convey the actors, their movements, the direction of movement, and the emotional tone through a single, integrated visual representation. This inherent efficiency and richness of sign language communication, when thought of directly, minimizes misunderstandings and allows for a more complete and authentic exchange of ideas.

Benefits for Hearing Individuals Learning Sign Language

Hearing individuals who endeavor to learn sign language often begin by translating English words and sentences into signs. However, adopting a conceptual thinking approach, where one learns to think in the visual-gestural grammar of sign language, dramatically accelerates fluency and comprehension. This cognitive shift allows learners to grasp the inherent logic and structure of sign languages, moving beyond rote memorization of signs.

For example, when learning to describe location or direction, thinking in sign language involves conceptualizing space as a grammatical element. Instead of thinking “the book is on the table” and then signing BOOK TABLE ON, a learner who thinks in sign language might establish a “space” for the table and then place the “book” within that spatial representation, signing BOOK and then pointing to the established table space and signing ON.

This visual mapping makes spatial relationships more intuitive and less reliant on English prepositions.

This approach also facilitates understanding idiomatic expressions and cultural nuances embedded within sign languages, which often do not have direct English equivalents. By thinking visually and spatially, learners can better appreciate the creative ways sign languages convey meaning.

Cognitive Advantages of Multilingualism Including Sign Languages

Research consistently highlights the cognitive benefits of multilingualism, and the inclusion of sign languages offers unique advantages. Engaging with a visual-gestural language alongside spoken languages can foster enhanced cognitive flexibility, improved executive functions, and greater metalinguistic awareness. The brain, by necessity, develops more robust pathways for managing and switching between different linguistic systems, including those with fundamentally different modalities.

Studies have indicated that individuals proficient in multiple languages, including sign languages, often exhibit:

- Enhanced Problem-Solving Skills: The ability to approach problems from multiple linguistic and conceptual perspectives can lead to more innovative solutions.

- Improved Memory and Attention: Managing different language systems requires sustained attention and strengthens working memory.

- Increased Creativity: Exposure to diverse linguistic structures and modes of expression can foster divergent thinking and creative output.

- Greater Empathy and Perspective-Taking: Learning a sign language often involves understanding the perspectives of a different community, fostering a broader worldview and enhanced empathy.

The cognitive benefits are not limited to mere language acquisition; they extend to a broader capacity for abstract thought and a more flexible approach to information processing.

Influence on Problem-Solving and Creative Expression

Thinking in sign language inherently cultivates a more visual and spatial approach to cognition, which can profoundly influence problem-solving and creative expression. The ability to manipulate concepts in a three-dimensional mental space, to represent relationships visually, and to utilize non-linear narrative structures can unlock new avenues for innovation.

In problem-solving, this visual-gestural thinking can manifest as the ability to “see” the components of a problem and their interrelationships more clearly. For instance, when faced with a complex system, a person thinking in sign language might mentally map out the connections and flows of information as if drawing a diagram in the air, identifying bottlenecks or potential solutions through spatial visualization.

Creative expression is also significantly impacted. Artists, writers, and designers who incorporate sign language concepts into their work can produce highly original pieces. This might involve creating visual art that mimics the flow and grammar of sign language, or developing narratives that are inherently visual and spatial. For example, a choreographer might draw inspiration from the spatial grammar of sign language to develop dance sequences that convey complex narratives or emotions through movement and form.

“Thinking in sign language is not just about signing words; it’s about seeing the world through a different lens, a lens that values visual storytelling and spatial relationships as fundamental to meaning.”

Illustrative Scenarios and Comparisons

Understanding how to think in sign language requires moving beyond direct translation and embracing a fundamentally different conceptual framework. This section will explore practical examples to highlight these distinctions, demonstrating how the visual-gestural nature of sign languages shapes thought processes and expression.

Action Description: English vs. Sign Language Conceptualization

Consider the simple action of a person walking across a room. An English speaker might think: “He walked across the room.” This is a linear, verb-centric description. A sign language thinker, however, would likely conceptualize this visually and spatially. They would first establish the “person” as a classifier or a sign, then the “room” as a spatial representation, and finally, depict the movement of the person through that space.

The emphasis is on the visual path and the dynamic relationship between the actor and the environment, rather than a singular verb.

Conceptualizing Abstract Ideas: English vs. Visual-Gestural Language

Abstract concepts, often expressed through metaphors and nuanced vocabulary in English, are approached differently in visual-gestural languages. While English might use words like “freedom,” “justice,” or “love,” sign languages often employ a combination of signs, facial expressions, and body language to convey the essence of these ideas.

| Concept | English Conceptualization | Sign Language Conceptualization (General Principles) |

|---|---|---|

| Freedom | Abstract noun, often associated with liberty, absence of constraint. Expressed through words like “free,” “liberty,” “independence.” | Visual representation of breaking chains, open space, or a bird flying. Facial expression conveying relief or expansiveness. |

| Justice | Abstract noun, concept of fairness and righteousness. Expressed through words like “fair,” “equal,” “right,” “law.” | Visual representation of scales balancing, or a hand striking a gavel to signify judgment or fairness. Can involve the concept of reciprocity. |

| Love | Abstract noun, complex emotion. Expressed through words like “affection,” “care,” “devotion,” “passion.” | Visual representation of a heart shape, hands forming a circle around the chest, or specific signs that convey warmth, closeness, and tenderness through movement and facial expression. |

Narrative Construction in Sign Language Thought

When constructing a narrative, an English thinker follows a sequential, sentence-by-sentence progression. In contrast, a sign language thinker often constructs a narrative more holistically and spatially. They might first establish the setting and characters within the signing space, then “play out” the events by moving those established entities through the space, using classifiers to represent different types of movement and interaction.

The entire scene can be presented as a visual tableau, with the flow of action dictated by the movement and relationships within that space, rather than a strict chronological order of words. This allows for simultaneous information to be conveyed, such as the emotional state of a character while they are performing an action.

Conveying Emotions and Intent in Visual-Gestural Thought

Emotions and intent are intrinsically woven into the fabric of visual-gestural communication. Facial expressions, body posture, and the intensity and speed of signs are not mere embellishments but crucial components of meaning. For instance, a sign for “happy” can be modified by the degree of smiling, the openness of the eyes, and the liveliness of the movement to convey anything from mild contentment to overwhelming joy.

Similarly, intent, such as asking a question versus making a statement, is often signaled by a specific eyebrow raise, head tilt, or a change in the non-manual markers accompanying the signs. When thinking in sign language, these visual cues are not added on; they are integral to the conceptualization and expression of the thought itself.

Final Review

In essence, embracing “How to Think in Sign Language, Not Just English” opens a gateway to richer communication and enhanced cognitive abilities. By moving beyond direct translation and engaging with the visual-gestural nature of sign languages, we unlock new dimensions of understanding, empathy, and creative expression. This journey fosters a deeper connection with the deaf community and offers profound benefits for all learners, proving that thinking in sign language is not just an alternative, but a powerful enhancement to our cognitive landscape.