Embarking on the journey of language acquisition is a rewarding endeavor, and understanding the critical juncture where vocabulary acquisition meets fluent conversation is paramount. This exploration delves into the nuanced shift from passively recognizing words to actively engaging in dynamic dialogue, offering a comprehensive guide for learners seeking to bridge this vital gap.

We will navigate the essential distinctions between rote memorization and genuine conversational ability, uncovering the cognitive transformations necessary for this progression. Furthermore, we will address the common hurdles encountered by language learners and provide actionable strategies to overcome them, ensuring a smoother and more effective transition to natural speech.

Understanding the Leap from Vocabulary to Fluency

Transitioning from a learner who can recognize and recall individual words to someone who can engage in spontaneous, natural conversation is a significant cognitive and practical leap. It moves beyond the passive acquisition of knowledge to the active application of that knowledge in dynamic, real-time situations. This shift requires developing new skills and overcoming inherent challenges in the language learning process.The fundamental difference lies in the transition from a static lexicon to a fluid communication system.

Memorizing words is akin to collecting individual bricks; fluency is the ability to construct a coherent and aesthetically pleasing building with those bricks, often on the fly. While vocabulary acquisition provides the raw materials, fluency involves the intricate process of selecting, arranging, and deploying these materials with speed, accuracy, and appropriate nuance. This necessitates a deeper engagement with grammar, pronunciation, cultural context, and the ability to process information and respond almost instantaneously.

Cognitive Shifts for Active Language Production

Moving from passive word recognition to active language production involves several crucial cognitive shifts. Initially, learners focus on decoding incoming language and retrieving stored word meanings. This process is often slow and deliberate. As learners progress, their brains begin to automate these processes, allowing for faster recognition and retrieval. The next critical shift is the ability to generate language.

This involves not just recalling words but also understanding and applying grammatical rules, sentence structures, and idiomatic expressions in real-time. This requires developing a mental framework that can predict, construct, and adapt linguistic output based on context and communicative intent. This automation reduces cognitive load, freeing up mental resources for higher-level thinking, such as understanding subtle meanings, expressing complex ideas, and engaging in social interaction.

Common Challenges in Applying Vocabulary to Conversation

Learners frequently encounter several common hurdles when attempting to integrate their learned vocabulary into real-time conversations. These challenges often stem from the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application.

The primary difficulties include:

- Processing Speed: The brain needs to process incoming speech, identify words and their meanings, formulate a response, and then produce that response, all within a very short timeframe. This often feels overwhelming, leading to pauses or incomplete sentences.

- Grammatical Accuracy Under Pressure: Applying grammatical rules correctly in the heat of conversation is much harder than when practicing in controlled exercises. Learners may revert to simpler sentence structures or make errors due to the cognitive load of real-time production.

- Fear of Making Mistakes: The anxiety associated with potential errors can paralyze learners, making them hesitant to speak. This fear can hinder their willingness to take risks, which is essential for improvement.

- Limited Exposure to Natural Speech: Textbooks and formal lessons often present language in a structured and sometimes artificial manner. Real conversations are filled with colloquialisms, contractions, and varying speeds, which can be difficult to follow and replicate.

- Lack of Confidence: Even with a strong vocabulary, a lack of confidence in one’s ability to communicate effectively can be a significant barrier. This self-doubt can prevent learners from initiating conversations or fully participating.

- Difficulty with Pragmatics and Nuance: Understanding and using language appropriately in different social contexts, including tone, politeness, and indirect communication, is a complex skill that goes beyond knowing individual word meanings.

Strategies for Active Vocabulary Application

Moving beyond simply memorizing individual words is a crucial step in achieving conversational fluency. This phase focuses on actively integrating your learned vocabulary into your daily speech, transforming passive knowledge into active skills. The following strategies are designed to bridge the gap between knowing a word and using it confidently and naturally in real-time communication.Applying new words immediately after learning them is key to cementing them in your memory and making them readily accessible for conversation.

This approach fosters a dynamic learning process where vocabulary acquisition is directly linked to practical usage.

Immediate Integration Techniques

To ensure new words become part of your active vocabulary, it is beneficial to employ methods that encourage their immediate use. This practice helps to bypass the mental block that can occur when trying to recall a word in a spontaneous conversation.

- Sentence Creation on the Spot: As soon as you learn a new word, create at least three different sentences using it. Vary the context and grammatical structure of these sentences to understand the word’s flexibility. For example, if you learn the word “ubiquitous,” you might create: “Smartphones have become ubiquitous in modern society.” “The scent of freshly baked bread was ubiquitous in the bakery.” “Finding reliable Wi-Fi is almost ubiquitous in urban areas.”

- Verbalization of Thoughts: Narrate your daily activities or thoughts aloud, intentionally incorporating newly learned words. This could involve describing your surroundings, planning your day, or reflecting on an event. This self-talk acts as a low-pressure practice environment.

- Role-Playing Scenarios: Engage in imaginary role-playing exercises. Assign yourself a character or a situation and try to converse using the new vocabulary. This helps in understanding how the words fit into dialogue and can reveal any awkward phrasing.

Sentence Construction Practice

Developing the ability to construct grammatically correct and meaningful sentences with a growing vocabulary is fundamental for fluid communication. This involves understanding not just the meaning of words but also their function within a sentence.

Practicing sentence construction is essential for building confidence and accuracy in spoken language. It allows you to experiment with different grammatical structures and to see how new words interact with existing ones.

- Targeted Sentence Drills: Focus on a specific grammatical structure or a set of related words and practice building sentences around them. For instance, if you are working on past tense verbs, create sentences using recently learned adjectives and nouns in the past tense.

- Sentence Transformation: Take simple sentences and rewrite them using more sophisticated vocabulary or different grammatical structures. This exercise enhances your ability to express the same idea in multiple ways.

- Using Sentence Starters: Employ common sentence starters like “I think that…”, “In my opinion…”, “One of the most important aspects is…”, and integrate your new vocabulary into these frameworks.

Active Recall and Contextual Utilization

The ability to recall and apply learned words in varied contexts is a hallmark of true fluency. This requires moving beyond rote memorization to understanding the nuances and appropriate usage of each word.

Actively recalling and using words in different situations solidifies your understanding and makes them readily available during conversations. This process helps to embed words into your long-term memory and to develop an intuitive sense of their usage.

- Flashcard with Context: When using flashcards, don’t just write the word and its definition. Include a sample sentence that demonstrates its usage in a real-world context. When reviewing, try to create a new sentence yourself before looking at the provided example.

- Word Association Games: Play games that involve associating new words with existing ones, synonyms, antonyms, or related concepts. This strengthens the neural pathways connected to the word, making recall easier.

- Thematic Vocabulary Grouping: Learn and practice words related to specific themes or topics (e.g., travel, food, technology). This allows you to build a robust vocabulary for particular conversational domains, making it easier to deploy related words together.

- Simulated Conversations: Engage in simulated conversations with language partners or even by recording yourself. Try to naturally weave in the vocabulary you’ve been practicing. The goal is to make the integration feel organic rather than forced.

Daily Practice Routine Prioritizing Active Usage

A structured daily routine that emphasizes active word usage over passive review is instrumental in accelerating the transition to conversational fluency. This approach ensures that learning is consistently translated into practice.

A well-designed daily practice routine should allocate significant time to actively using your vocabulary, rather than solely focusing on reviewing definitions. This shift in emphasis is critical for developing spontaneous speaking skills.

- Morning Vocabulary Activation (10-15 minutes): Begin your day by reviewing a small set of recently learned words. Immediately after, spend five minutes speaking or writing sentences using these words, describing your morning routine or plans for the day.

- Midday Contextual Application (5-10 minutes): During a break, pick one or two words and actively look for opportunities to use them in your thoughts or in brief written messages (e.g., emails, social media posts).

- Evening Conversational Practice (20-30 minutes): Dedicate a substantial portion of your evening to active speaking. This could involve talking to a language partner, participating in online language exchange groups, or practicing self-talk with a specific vocabulary goal in mind. Try to use at least 5-10 new words during this session.

- Reflection and Targeted Review (5 minutes): At the end of the day, briefly reflect on which new words you successfully used and which ones you struggled with. Make a note of words that require more active practice in the coming days.

“The difference between knowing a word and using a word is the practice of speaking.”

Developing Conversational Mechanics

Transitioning from a robust vocabulary to fluid, natural conversation involves mastering the art of spoken communication. This goes beyond simply knowing words; it’s about how those words are delivered and how we interact in real-time exchanges. Developing conversational mechanics equips you with the tools to sound more natural, understand others better, and participate actively and smoothly in dialogues.Natural speech is a complex symphony of sounds, timing, and emphasis.

Intonation, the rise and fall of our voice, conveys emotion and meaning, differentiating questions from statements or expressing sarcasm. Rhythm refers to the beat and flow of speech, while stress, the emphasis placed on certain syllables or words, highlights key information and guides the listener’s attention. Without attention to these elements, speech can sound monotonous, unclear, or even grammatically correct but unnatural.

Intonation, Rhythm, and Stress in Natural Speech

Mastering the subtle nuances of intonation, rhythm, and stress is crucial for sounding like a native speaker and ensuring your message is understood as intended. These prosodic features are as important as the words themselves in conveying meaning, emotion, and attitude.

- Intonation: This refers to the pitch changes in your voice. For instance, a rising intonation at the end of a sentence typically signals a question, while a falling intonation indicates a statement. Exaggerated or incorrect intonation can lead to misunderstandings or make speech sound robotic.

- Rhythm: Spoken language has a natural rhythm, created by the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables and pauses. A smooth, consistent rhythm makes speech easier to follow. Languages have different rhythmic patterns, and adopting the target language’s rhythm can significantly improve naturalness.

- Stress: Word stress (emphasizing a particular syllable within a word) and sentence stress (emphasizing key words in a sentence) are vital. Incorrect stress can alter the meaning of a word or sentence, or make it difficult to comprehend. For example, stressing the wrong syllable in “photograph” (PHO-to-graph vs. pho-TO-graph) changes its meaning and pronunciation.

Improving Listening Comprehension for Spoken Language

Effective communication is a two-way street. To converse naturally, you must be able to understand what others are saying, even when they speak quickly, use colloquialisms, or employ different accents. Developing strong listening comprehension skills is paramount.

To enhance your ability to understand spoken language, particularly with diverse accents, consistent and varied exposure is key. This involves actively engaging with authentic spoken materials and practicing specific listening strategies.

Exercises for Listening Comprehension

Regular practice with a variety of authentic audio and video materials will gradually train your ear to recognize different speech patterns, accents, and vocabulary in context.

- Active Listening with Transcripts: Start by listening to short audio clips or video segments. Listen once without any aids. Then, listen again while reading a transcript. Finally, listen a third time without the transcript, focusing on how the spoken words match the written text. This helps you connect sounds with words and identify where you might be missing information.

- Accent Exposure: Seek out content from speakers with various regional and international accents. This could include news broadcasts from different countries, interviews with people from diverse backgrounds, or films and TV shows set in different locations. Pay attention to common pronunciation differences and intonation patterns.

- Dictation Practice: Listen to a sentence or short passage and try to write it down exactly as you hear it. This forces you to focus on every word and sound. Gradually increase the length and complexity of the dictation material.

- Summarization Tasks: After listening to a podcast episode, a lecture, or a conversation, try to summarize the main points in your own words, either verbally or in writing. This tests your understanding of the overall message.

- Identifying Key Information: Practice listening for specific details. For example, listen to a news report and try to identify the who, what, when, where, and why. This hones your ability to extract crucial information even in fast-paced speech.

Understanding and Responding to Conversational Cues

Conversations are not just a series of statements; they are dynamic exchanges governed by unspoken rules and signals. Understanding and responding to conversational cues allows you to participate smoothly and appropriately, demonstrating active engagement and social awareness.

Conversational cues are the subtle signals that guide the flow of interaction. They include verbal and non-verbal elements that indicate a speaker’s intentions, emotional state, and readiness to continue or yield the floor. Recognizing these cues is essential for effective dialogue.

- Verbal Cues: These include phrases that signal a desire to speak (e.g., “Excuse me,” “If I could just add…”), to yield the floor (e.g., “What do you think?”), to show agreement or understanding (e.g., “Uh-huh,” “I see”), or to seek clarification (e.g., “What do you mean by that?”).

- Non-Verbal Cues: Body language plays a significant role. Eye contact, nodding, facial expressions, and posture can all indicate engagement, agreement, or a desire to interject. A speaker leaning forward might signal eagerness to speak, while looking away could indicate a pause or discomfort.

- Responding to Cues: Practice actively looking for these cues. When someone pauses and makes eye contact, it might be your cue to speak. If someone nods and says “yes,” they are likely agreeing. Learning to interpret these signals helps you know when to speak, when to listen, and how to react appropriately.

- Practicing Active Listening: Truly listening involves more than just hearing words. It means paying attention to the speaker’s tone, body language, and the underlying message. Paraphrasing what you’ve heard (“So, if I understand correctly, you’re saying…”) is a powerful way to confirm understanding and show you are engaged.

Practicing Turn-Taking and Maintaining Conversational Flow

Smooth turn-taking is the backbone of any natural conversation. It ensures that dialogue progresses logically, with each participant having an opportunity to contribute without awkward interruptions or prolonged silences. Maintaining this flow requires practice and an awareness of conversational rhythm.

The ability to seamlessly switch speaking roles, known as turn-taking, and to keep the conversation moving forward is a skill that can be consciously developed. This involves understanding the natural pauses and transitions in dialogue.

- Recognizing Turn-Taking Signals: As mentioned, verbal and non-verbal cues signal when a speaker is about to finish their turn. Practice identifying these cues, such as a slight pause, a change in intonation, or direct eye contact with you.

- Practicing Interjections: Use short interjections like “Oh,” “Really,” “Wow,” or “Uh-huh” at appropriate moments to show you are listening and engaged. These small verbal affirmations can fill brief pauses and encourage the speaker to continue, preventing premature silence.

- Using Transition Phrases: Employ transition phrases to smoothly enter a conversation or to shift the topic. Examples include “Speaking of X,” “On another note,” “That reminds me,” or “Going back to what you said earlier.”

- Simulated Conversations: Engage in role-playing exercises with a language partner or tutor. Practice initiating conversations, responding to prompts, and intentionally practicing handing over the speaking turn. Experiment with different ways to end your turn and invite the other person to speak.

- Handling Pauses and Silences: Not all pauses are awkward. Sometimes a pause is for thinking. Instead of rushing to fill every silence, learn to tolerate brief pauses. If a silence becomes prolonged, you can gently re-engage by asking a clarifying question or offering a related thought.

- Observing Native Speakers: Pay close attention to how native speakers manage turn-taking in real-life situations, such as in cafes, meetings, or social gatherings. Observe their body language, the length of their pauses, and the phrases they use to join or leave the conversation.

Building Confidence and Reducing Hesitation

Transitioning from a passive learner of words to an active conversationalist involves overcoming significant psychological hurdles. This stage focuses on developing the inner resilience and practical strategies needed to speak with greater ease and conviction. Many learners find themselves held back not by a lack of vocabulary, but by the internal anxieties associated with speaking a new language.The fear of making mistakes is a pervasive barrier, often stemming from a desire for perfection or a negative past experience.

This fear can lead to a mental block, where perfectly good vocabulary and grammar are inaccessible in the heat of the moment. Recognizing these psychological patterns is the first step towards dismantling them and fostering a more fluid speaking experience.

Psychological Barriers to Fluent Speaking

Several psychological factors commonly impede fluent speech in a second language. These include the fear of judgment from native speakers or fellow learners, the anxiety of forgetting words or grammar rules mid-sentence, and a general lack of self-belief in one’s own linguistic abilities. Perfectionism can also be a significant hindrance, as learners may feel they must speak flawlessly before attempting any real conversation.

This often results in a cycle of avoidance, where the opportunity to practice and improve is missed due to the fear of imperfection.Another common barrier is the internalized belief that one is “not good at languages,” which can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. This belief often arises from early negative learning experiences or unfavorable comparisons with others. Overcoming these barriers requires a conscious effort to reframe negative thought patterns and build a more supportive internal dialogue.

Techniques for Overcoming the Fear of Making Mistakes

The key to overcoming the fear of mistakes lies in reframing them not as failures, but as essential components of the learning process. Every error, when analyzed, provides valuable insight into areas that need further attention and practice.

- Embrace Imperfection: Understand that making mistakes is not only normal but expected when learning a new language. Even native speakers make slips of the tongue. The goal is communication, not flawless delivery.

- Focus on Communication Over Perfection: Prioritize getting your message across effectively. Native speakers are generally more forgiving and appreciative of the effort to communicate than they are critical of minor errors.

- Practice Self-Compassion: Treat yourself with the same kindness and understanding you would offer a friend learning a new skill. Acknowledge your progress and effort, rather than solely focusing on shortcomings.

- Analyze Mistakes Constructively: Instead of dwelling on an error, try to understand why it happened. Was it a vocabulary issue, a grammatical misunderstanding, or a pronunciation problem? This analysis turns mistakes into learning opportunities.

- Seek Low-Stakes Practice: Engage in speaking activities where the pressure is minimal, such as practicing with a patient language partner, a tutor, or even speaking aloud to yourself.

The Role of Self-Encouragement and Positive Self-Talk

Self-encouragement and positive self-talk are powerful tools that can significantly impact a language learner’s confidence and progress. The internal dialogue one has with oneself plays a crucial role in shaping motivation and resilience. Negative self-talk can undermine efforts, leading to frustration and a reluctance to speak. Conversely, positive affirmations and self-praise can reinforce progress and build a stronger sense of capability.

“My voice is my tool for connection. Each word I speak brings me closer to fluency.”

Regularly engaging in positive self-talk can help to counteract the negative voices of self-doubt. This involves consciously replacing critical thoughts with supportive and encouraging ones. For instance, instead of thinking “I can’t say this,” try “I will try my best to express this, and it’s okay if it’s not perfect.” This shift in perspective can create a more conducive mental environment for speaking practice.

Plan for Gradually Increasing Speaking Exposure

A structured approach to increasing speaking exposure can help learners build confidence incrementally, moving from less intimidating to more challenging situations. This gradual exposure helps to desensitize learners to the anxiety associated with speaking.

- Start with Solitary Practice: Begin by speaking aloud to yourself. Read texts, describe your surroundings, or narrate your daily activities in the target language. This allows for practice without external pressure.

- Engage with Recordings: Record yourself speaking and listen back. This helps identify areas for improvement in pronunciation and fluency without the immediate stress of a live conversation.

- Practice with Familiar Material: Rehearse conversations or monologues based on topics you are very comfortable with. This builds confidence through repetition and mastery of known content.

- Join Language Exchange Groups (Online/Offline): Participate in low-pressure language exchange sessions where the focus is on mutual learning and practice. Many platforms offer informal settings for this.

- Seek Out Structured Conversations: Engage with tutors or conversation partners who are trained to guide and support learners. They can provide constructive feedback in a safe environment.

- Attend Language Meetups or Social Events: Gradually introduce yourself to informal social gatherings focused on language learning. These provide opportunities to interact in more relaxed, real-world scenarios.

- Initiate Short Interactions: Begin by initiating brief conversations in everyday situations, such as ordering food, asking for directions, or making small talk with shopkeepers.

- Participate in Role-Playing: Practice specific conversational scenarios through role-playing. This can be done with a partner or even by yourself, preparing for common interactions.

This progressive exposure allows learners to build a foundation of confidence and competence, making more complex conversational challenges feel increasingly manageable.

Immersive Learning and Real-World Practice

Moving beyond rote memorization and structured exercises is crucial for true language fluency. Immersive learning environments and consistent real-world practice are the cornerstones of transforming vocabulary knowledge into natural, spontaneous conversation. This approach allows learners to internalize language patterns, understand cultural nuances, and develop the confidence to communicate effectively in diverse situations.Engaging with native speakers offers unparalleled benefits for language acquisition.

It provides direct exposure to authentic pronunciation, intonation, and idiomatic expressions that are often difficult to replicate through textbooks alone. This interaction fosters a deeper understanding of how language is used in everyday contexts, accelerating the learning curve and making the process more enjoyable and motivating.

Benefits of Engaging with Native Speakers

Direct interaction with native speakers provides a rich learning environment that significantly enhances language acquisition. This exposure goes beyond grammar rules and vocabulary lists, offering insights into the natural flow and rhythm of the language.

- Authentic Pronunciation and Intonation: Hearing and mimicking native speakers helps learners develop accurate pronunciation and a natural intonation pattern, making their speech more understandable and fluid.

- Exposure to Idiomatic Expressions and Slang: Native speakers naturally incorporate common idioms, slang, and colloquialisms, which are essential for sounding natural and comprehending everyday conversations.

- Cultural Nuances and Context: Language is deeply intertwined with culture. Interacting with native speakers provides direct insight into cultural norms, social etiquette, and the appropriate use of language in various social settings.

- Improved Listening Comprehension: Constant exposure to different accents and speaking speeds hones listening skills, enabling learners to better understand a wider range of speakers and conversational contexts.

- Enhanced Speaking Fluency and Confidence: Regular practice in real conversations builds confidence and reduces hesitation, allowing learners to express themselves more freely and spontaneously.

- Immediate Feedback and Correction: Native speakers can offer instant feedback on grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation, helping learners identify and correct mistakes in real-time.

Finding Language Exchange Partners and Conversation Groups

Actively seeking opportunities to speak with native speakers is a fundamental step in language immersion. Fortunately, numerous resources and platforms exist to facilitate these connections, making it easier than ever to find suitable partners and groups.The key is to be proactive and explore various avenues. Online platforms, local community centers, and educational institutions often host language exchange programs or conversation meetups.

Consistency in participation is vital for building rapport and making significant progress.

- Online Language Exchange Platforms: Websites and apps like HelloTalk, Tandem, and Speaky connect learners with native speakers for text, voice, and video calls. These platforms often have built-in translation tools and features to help initiate conversations.

- Local Meetup Groups: Platforms like Meetup.com host numerous language exchange groups in cities worldwide. These groups offer face-to-face interaction in a relaxed social setting, often at cafes or community centers.

- University Language Departments: Many universities have language exchange programs or clubs that welcome community members. Students often seek partners to practice their English or other target languages.

- Community Centers and Libraries: Local community centers and libraries sometimes organize language conversation groups or cultural exchange events, providing accessible opportunities for practice.

- Social Media Groups: Facebook and other social media platforms host many language-specific groups where learners can find partners or announce their interest in language exchange.

- Formal Tutoring Services: While not strictly exchange, online tutoring platforms like italki or Preply offer sessions with native speakers at various price points, providing structured conversation practice and professional guidance.

Scenarios for Practicing Common Conversational Topics

To maximize the effectiveness of practice sessions, it is beneficial to prepare for common conversational scenarios. Having a framework for these discussions can reduce anxiety and ensure that learners can engage meaningfully from the outset.These scenarios cover fundamental aspects of getting to know someone and discussing daily life, providing a solid foundation for more complex conversations. Practicing these will build confidence and familiarity with essential vocabulary and sentence structures.

Introductions and Getting to Know Someone

This is the most fundamental conversational scenario, crucial for initiating any interaction. It involves sharing basic personal information and showing interest in the other person.

- Greeting and Initial Exchange: “Hello,” “Hi, how are you?” “I’m doing well, thank you. And you?”

- Stating Your Name and Origin: “My name is [Your Name]. I’m from [Your Country/City].” “It’s nice to meet you, [Their Name].”

- Asking About Their Origin: “Where are you from?” “What brings you here?”

- Discussing Profession or Studies: “What do you do?” “I’m a [Your Profession].” or “I’m a student, studying [Your Major].”

- Expressing Reasons for Learning the Language: “I’m learning [Language] because…” (e.g., “I love the culture,” “I plan to travel there,” “It’s for my job”).

Hobbies and Interests

Discussing hobbies is an excellent way to find common ground and engage in more personal conversations. It allows for the use of descriptive language and expressions of enthusiasm.

- Asking About Hobbies: “What do you like to do in your free time?” “Do you have any hobbies?”

- Sharing Your Hobbies: “I enjoy [Hobby 1], [Hobby 2], and [Hobby 3].” “My favorite hobby is…”

- Asking Follow-up Questions: “How did you get into [Hobby]?” “What do you like most about it?” “Have you been doing it for long?”

- Discussing Specific Activities: “I love reading, especially [Genre].” “I’m a big fan of [Sport] and try to watch/play it whenever I can.” “I enjoy hiking and exploring new trails.”

Daily Routines

Talking about daily routines provides practical vocabulary related to time, activities, and common daily events. It helps learners describe their typical day and understand others’.

- Describing Your Morning: “I usually wake up around [Time].” “First, I [Activity].” “Then, I have breakfast.”

- Discussing Work/Study Day: “I start work/class at [Time].” “My typical workday involves [Tasks].” “I usually have lunch at [Time].”

- Talking About Evening Activities: “After work/class, I often [Activity].” “In the evening, I like to [Activity].” “I usually go to bed around [Time].”

- Asking About Their Routine: “What does a typical day look like for you?” “What time do you usually start your day?”

Authentic Materials for Understanding Natural Dialogue

While direct interaction is paramount, supplementing practice with authentic materials significantly enhances comprehension of natural speech patterns, vocabulary, and cultural context. These materials expose learners to language as it is genuinely used by native speakers in various real-life situations.The goal is to move beyond simplified language found in textbooks and embrace the complexity and richness of everyday communication. By regularly engaging with these resources, learners can improve their ability to understand fast-paced conversations, identify nuances, and learn new expressions organically.

- Podcasts: Podcasts designed for language learners, as well as those created for native speakers on topics of interest, offer diverse accents, speaking speeds, and conversational styles. Examples include “Coffee Break [Language]” for structured learning or “Stuff You Should Know” for general interest.

- Short Videos and Vlogs: Platforms like YouTube are rich with content. Short videos, vlogs, and interviews provide visual context, making it easier to understand spoken language. Look for channels related to hobbies, travel, or daily life in target language countries.

- TV Shows and Movies: Watching shows and movies with subtitles (initially in your native language, then the target language, and eventually without) is a highly effective method. Start with genres that are dialogue-heavy and familiar.

- News Broadcasts and Documentaries: These sources offer more formal language and clear articulation, which can be excellent for developing listening comprehension of standard pronunciation.

- Music: Listening to music in the target language, especially with accompanying lyrics, helps with rhythm, pronunciation, and learning new vocabulary in a memorable way.

- Audiobooks: Similar to podcasts, audiobooks provide extended listening practice. Starting with simpler narratives or children’s stories can be beneficial.

Mastering Conversational Connectors and Fillers

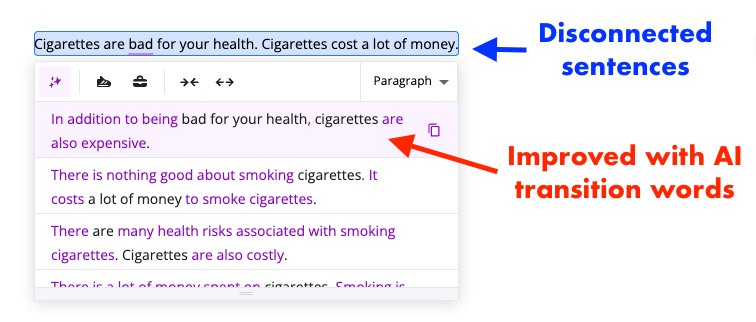

Moving beyond individual words and phrases, the ability to connect ideas smoothly and manage the flow of conversation is a hallmark of fluency. This section delves into the essential tools that native speakers use to bridge gaps in thought, add emphasis, and maintain a natural rhythm: conversational connectors and fillers. Understanding and employing these elements effectively can significantly enhance your confidence and the naturalness of your spoken language.The strategic use of transition words, phrases, and appropriate fillers transforms a series of isolated statements into a cohesive and engaging dialogue.

They act as the glue that holds sentences and ideas together, signaling relationships between thoughts and providing the speaker with a moment to gather their next words without creating an awkward silence. Mastering these components is key to sounding less like you are reciting memorized phrases and more like you are genuinely participating in a dynamic exchange.

Common Transition Words and Phrases in Natural Speech

Transition words and phrases are the signposts of language, guiding listeners through the progression of your thoughts. They indicate relationships such as addition, contrast, cause and effect, and sequence, making your speech easier to follow and understand. Their appropriate application demonstrates a sophisticated grasp of the language.Some of the most frequently used transition words and phrases in natural speech include:

- For adding information: and, also, furthermore, moreover, in addition, besides, what’s more

- For contrasting ideas: but, however, on the other hand, in contrast, nevertheless, yet, still

- For showing cause and effect: so, therefore, consequently, as a result, because, since, thus

- For sequencing or ordering: first, second, next, then, finally, afterwards, subsequently

- For giving examples: for example, for instance, such as, to illustrate, like

- For summarizing or concluding: in conclusion, to sum up, in short, all in all, overall

The Function of Filler Words in Maintaining Conversational Momentum

Filler words, often referred to as “hesitation sounds” or “discourse markers,” are sounds or words that speakers use to fill pauses in speech. While sometimes perceived negatively, when used judiciously, they serve a crucial function: they signal to the listener that you are still thinking and intend to continue speaking, thereby preventing interruptions and maintaining the flow of the conversation.

They are a natural part of human speech, even among native speakers.Examples of common filler words and their functions include:

- “Um” and “Uh”: These are perhaps the most universal fillers, indicating a pause for thought or retrieval of a word. They signal that the speaker is processing information or searching for the right vocabulary.

- “Like”: Used in informal contexts, “like” can serve to introduce an example, convey approximation, or simply act as a pause marker. For instance, “It was, like, really cold outside.”

- “You know”: This phrase is often used to check for listener comprehension or to emphasize a point that the speaker assumes the listener already agrees with or understands. For example, “We need to leave by five, you know, to avoid the traffic.”

- “Well”: Often used to begin a response, introduce a new idea, or indicate a slight hesitation before answering. “Well, I’m not sure about that.”

- “So”: Can be used to introduce a consequence, a summary, or simply to transition to the next point. “So, what did you think of the movie?”

The key to using fillers effectively is moderation. Overuse can make a speaker sound hesitant or uncertain, but occasional, natural-sounding fillers contribute to a more relaxed and authentic conversational style.

Effective Use of Connectors and Fillers Without Sounding Unnatural or Repetitive

The art of using conversational connectors and fillers lies in their natural integration into your speech patterns. The goal is to employ them in a way that enhances clarity and flow, rather than detracting from your message. This involves developing an ear for how native speakers use these elements and practicing their application in various contexts.To avoid sounding unnatural or repetitive:

- Vary your choices: Instead of relying on just one or two fillers or connectors, learn a variety of options for similar functions. For example, if you often start sentences with “so,” try incorporating “therefore,” “consequently,” or “thus” when appropriate.

- Listen and observe: Pay close attention to how native speakers use these tools in podcasts, movies, and real-life conversations. Notice the situations in which they employ fillers and the types of connectors they choose to link their ideas.

- Practice in low-stakes environments: Rehearse your use of connectors and fillers in practice conversations with language partners or in front of a mirror. This helps you internalize their usage without the pressure of a real-time conversation.

- Focus on meaning and context: Ensure that your chosen connector or filler accurately reflects the relationship between your ideas and fits the overall tone of the conversation. A connector that is grammatically correct might still sound out of place if it doesn’t match the context.

- Use fillers strategically: Employ fillers primarily when you genuinely need a moment to think. They should not be a crutch for every pause, but rather a tool to manage natural thinking time.

Repetition can be mitigated by building a robust vocabulary of these bridging words and phrases. This allows for more nuanced expression and prevents your speech from becoming monotonous.

A List of Conversational Connectors Categorized by Function

To facilitate a more structured approach to incorporating connectors, here is a categorized list of common phrases. This resource can be used for practice and reference when aiming to improve the coherence of your spoken language.

Adding Information

These connectors are used to introduce additional points or expand on a previous statement.

- And

- Also

- Furthermore

- Moreover

- In addition

- Besides

- What’s more

- Not only… but also

Contrasting Ideas

These are essential for presenting opposing viewpoints or highlighting differences.

- But

- However

- On the other hand

- In contrast

- Nevertheless

- Yet

- Still

- Whereas

- While

Showing Cause and Effect

These help to establish logical connections between events or ideas.

- So

- Therefore

- Consequently

- As a result

- Because

- Since

- Thus

- Due to

- Owing to

Providing Examples

These introduce illustrations to clarify or support a point.

- For example

- For instance

- Such as

- To illustrate

- Like

- In particular

Summarizing or Concluding

These signal the end of a discussion or a recap of main points.

- In conclusion

- To sum up

- In short

- All in all

- Overall

- In brief

- To conclude

Sequencing or Ordering

These are vital for presenting information in a logical order, especially in narratives or explanations.

- First

- Second

- Third

- Next

- Then

- Finally

- Afterwards

- Subsequently

- Before

- After

Introducing a Condition

These phrases set up a hypothetical situation.

- If

- Unless

- Provided that

- As long as

Expressing Agreement or Disagreement

These are useful for responding to others’ statements.

- I agree

- That’s true

- You’re right

- I disagree

- I don’t think so

- On the contrary

Adapting to Different Conversational Contexts

Moving beyond a foundational vocabulary and basic sentence structures is essential for effective communication. True fluency involves understanding the nuances of how language is used in various social and professional settings. This section focuses on equipping you with the skills to navigate these diverse environments, ensuring your communication is not only understood but also appropriate and impactful.Being able to adjust your speaking style is a hallmark of sophisticated communication.

The way you address a close friend will differ significantly from how you interact with a potential employer or a senior colleague. Recognizing and implementing these shifts demonstrates social intelligence and respect for the conversational context.

Speaking Style Adjustment Based on Formality

The level of formality in a conversation dictates the choice of vocabulary, sentence complexity, and overall tone. In formal settings, such as business meetings, academic presentations, or official correspondence, a more structured and precise approach is preferred. This often involves using complete sentences, avoiding slang and contractions, and employing more sophisticated vocabulary. Conversely, informal settings, like conversations with friends or family, allow for greater flexibility, including the use of colloquialisms, contractions, and a more relaxed tone.Here are key considerations when adjusting your speaking style:

- Vocabulary Choice: Formal situations require precise and often more elaborate words. For example, instead of “get,” you might use “obtain” or “acquire.” In informal settings, “get” is perfectly acceptable.

- Grammatical Structure: Formal language tends to favor complete sentences and avoids sentence fragments. Contractions (e.g., “don’t,” “can’t”) are generally avoided in very formal writing and speaking, though their use is common and acceptable in most professional contexts.

- Tone and Politeness: Formal conversations often involve a more deferential tone, using phrases like “would you mind,” “please,” and “thank you” more frequently. Informal conversations can be more direct and expressive.

- Use of Pronouns: While “you” is standard, formal contexts might sometimes use more indirect address or titles (e.g., “Mr. Smith,” “Professor Davis”) instead of just first names.

Understanding and Using Idiomatic Expressions and Colloquialisms

Idioms are phrases whose meaning cannot be deduced from the literal meaning of their individual words. Colloquialisms are informal words and phrases used in everyday conversation. Mastering these elements is crucial for sounding natural and understanding native speakers. However, their use is highly context-dependent.To effectively incorporate idioms and colloquialisms:

- Exposure and Observation: Pay close attention to how native speakers use these expressions in movies, TV shows, podcasts, and real-life conversations. Note the context in which they appear.

- Contextual Learning: Learn idioms and colloquialisms within their specific contexts. Understanding the situation in which they are used will help you grasp their meaning and appropriate application. For example, “break a leg” is used to wish someone good luck, typically before a performance.

- Gradual Integration: Start by using common and widely understood idioms. Avoid overly obscure or regional expressions until you are more confident.

- Understanding Nuance: Be aware that some idioms can have multiple meanings or can be used ironically. It’s important to understand the subtle differences.

A helpful strategy is to maintain a personal log of idioms and colloquialisms encountered, along with their meanings and example sentences.

Strategies for Asking Clarifying Questions and Paraphrasing

Ensuring mutual understanding is a cornerstone of any successful conversation. Asking clarifying questions and paraphrasing are active listening techniques that prevent misunderstandings and demonstrate engagement.Effective strategies include:

- Asking for Repetition: If you miss something or don’t understand, polite requests like “Could you please repeat that?” or “I’m sorry, I didn’t quite catch that” are appropriate.

- Requesting Elaboration: To gain more detail or understanding, use phrases like “Could you elaborate on that?” or “What do you mean by…?”

- Paraphrasing for Confirmation: Restate what you believe you heard in your own words. This allows the speaker to confirm your understanding or correct any misinterpretations. For example, “So, if I understand correctly, you’re suggesting we focus on the marketing aspect first?”

- Checking for Specifics: When dealing with complex information, asking for specific examples can be very useful. “Could you give me an example of what that would look like in practice?”

These techniques are valuable in both formal and informal settings, though the phrasing might vary. In a formal setting, you might say, “To ensure I’ve grasped your point accurately, are you proposing that we prioritize the initial phase of the project?”

Framework for Practicing Role-Playing Various Social and Professional Interactions

Role-playing is a highly effective method for practicing conversational skills in a safe and controlled environment. It allows you to experiment with different scenarios, receive feedback, and build confidence.A structured approach to role-playing can be organized as follows:

- Identify Scenarios: Brainstorm a list of common social and professional situations you anticipate encountering. This could include:

- Job interviews

- Networking events

- Customer service interactions

- Team meetings

- Casual conversations at a party

- Making a complaint

- Giving a presentation introduction

- Define Roles and Objectives: For each scenario, clearly define the roles of the participants and their specific goals within the conversation. For example, in a job interview role-play, one person is the interviewer seeking to assess qualifications, and the other is the candidate aiming to impress.

- Script or Artikel Key Points: While spontaneous conversation is the ultimate goal, it can be helpful to have a general Artikel or key points to cover, especially in the initial stages of practice. This ensures that the core elements of the interaction are addressed.

- Engage in the Role-Play: Conduct the role-play, focusing on applying the communication strategies learned, including adapting your style, using appropriate language, and employing active listening.

- Debrief and Provide Feedback: After the role-play, dedicate time to discussing what went well and what could be improved. Provide constructive feedback on aspects like clarity, appropriateness of language, confidence, and effectiveness in achieving objectives.

- Repeat and Refine: Cycle through different scenarios and roles, gradually increasing the complexity and spontaneity of the interactions.

This structured practice helps to internalize conversational patterns and build the flexibility needed to adapt to real-world situations with greater ease and confidence.

Wrap-Up

In essence, transforming a vocabulary list into a fluid conversation requires a multifaceted approach that extends beyond mere word memorization. By actively applying new language, honing conversational mechanics, building confidence, embracing immersion, mastering connectors, and adapting to diverse contexts, learners can confidently navigate the complexities of real-time communication. This journey empowers individuals to not only speak a language but to truly connect and express themselves with ease and authenticity.