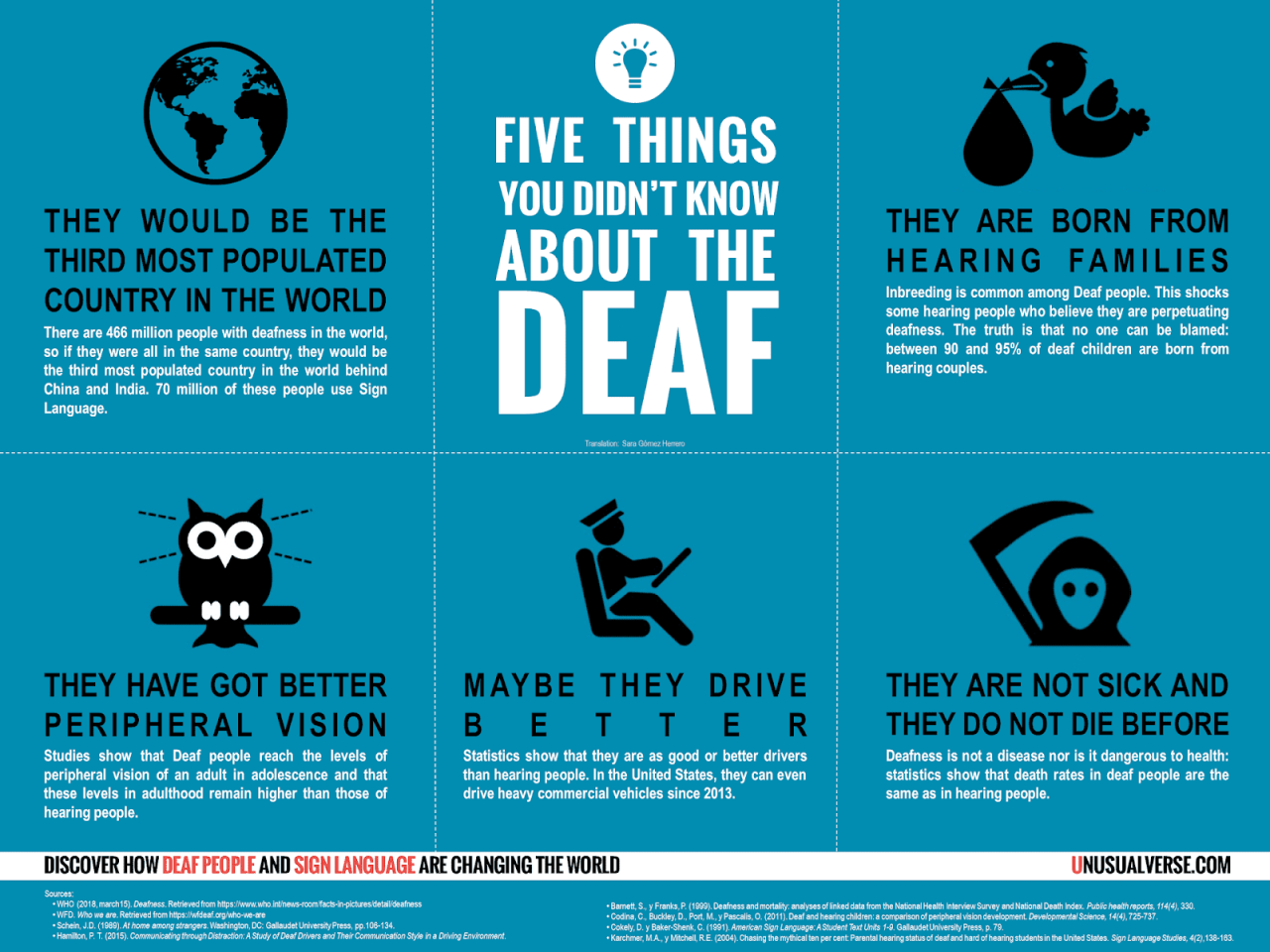

How to Understand the Basics of Deaf Culture invites you on a journey to explore a vibrant and rich world. This exploration delves into the foundational elements that shape Deaf identity, moving beyond a purely medical perspective to embrace the cultural significance and lived experiences of Deaf individuals.

We will uncover the pivotal role of sign language as the heart of Deaf communication and community, examine the intricate social structures and traditions that bind Deaf people together, and illuminate the unique etiquette and communication styles that foster understanding. Furthermore, we will trace the historical threads and ongoing advocacy efforts that have shaped Deaf rights and recognition, and explore the profound concept of “Deafhood” as a distinct cultural identity.

Understanding the spectrum of audiological experiences and the diverse perceptions of technology within the community, alongside the powerful expressive forms of visual storytelling and art, will provide a comprehensive picture of this fascinating culture.

Defining Deaf Culture: Core Components

Deaf culture is a vibrant and multifaceted aspect of human experience, encompassing shared values, traditions, and a distinct way of life. It is crucial to understand that “Deaf” in this context is not merely a medical diagnosis but a cultural identity. This identity is forged through shared experiences, particularly the use of sign language, and a collective sense of belonging within Deaf communities.The essence of Deaf culture lies in its unique social and linguistic characteristics.

These elements coalesce to form a rich tapestry of traditions and perspectives that differentiate Deaf individuals from their hearing counterparts. Recognizing these core components is the first step towards appreciating the depth and richness of Deaf culture.

Shared Language as a Cornerstone

At the heart of Deaf culture lies a shared language, most prominently sign language. Sign languages are fully developed, natural languages with their own unique grammars, syntax, and vocabularies, distinct from spoken languages. For many Deaf individuals, sign language is their native tongue and the primary means of communication and connection.The significance of sign language extends beyond mere communication; it is the primary vehicle for transmitting cultural knowledge, values, and history.

It fosters a strong sense of community and belonging, allowing for nuanced expression and deep understanding among its users.

“Sign language is not just a visual representation of spoken words; it is a complete language that carries its own cultural nuances and richness.”

Examples of how sign language functions as a cornerstone include:

- Storytelling and History: Oral traditions in hearing cultures are mirrored in the rich tradition of storytelling in sign language, preserving history, folklore, and personal narratives within the Deaf community.

- Artistic Expression: Sign language is the foundation for various Deaf art forms, including poetry, theater, and performance art, which leverage the visual and spatial aspects of the language.

- Education and Transmission: Sign language is essential for the effective education of Deaf children, ensuring access to information and fostering cognitive development. It is the primary medium through which cultural norms and values are passed down through generations.

- Social Interaction: Everyday conversations, jokes, and expressions of emotion are all facilitated through sign language, creating a robust and interactive social environment.

Cultural Norms and Values

Deaf communities often exhibit distinct cultural norms and values that shape social interactions and community life. These are developed organically within the community and reflect the shared experiences and perspectives of its members.These norms and values are crucial for maintaining social cohesion and ensuring that individuals feel understood and respected within the community. They guide behavior, foster mutual support, and contribute to a strong collective identity.Some prevalent cultural norms and values within Deaf communities include:

- Emphasis on Visual Communication: A strong reliance on visual cues, such as eye contact, facial expressions, and body language, is paramount. These elements are not just supplementary but integral to effective communication and understanding.

- Respect for Elders and Knowledge Keepers: There is often a deep respect for older Deaf individuals who are seen as custodians of the language, history, and traditions of the community.

- Directness in Communication: Communication can be more direct compared to some hearing cultures, with a focus on clarity and explicitness to ensure understanding.

- Community Support and Interdependence: A strong sense of mutual support and interdependence is common, where members look out for each other and readily offer assistance.

- Value of Deaf Schools: Deaf schools are often highly valued as places where Deaf children can learn in their native sign language and connect with peers and role models who share their experiences.

- Awareness of Auditory Oppression: A shared awareness of historical and ongoing societal biases or discrimination against Deaf people, sometimes referred to as “auditory oppression,” can foster solidarity.

“Deaf” as an Identity, Not Solely a Medical Condition

It is essential to differentiate between being “deaf” (a medical audiological condition) and being “Deaf” (a cultural identity). The capitalized “D” signifies an individual who identifies with and participates in Deaf culture, embracing its language, values, and community.This distinction highlights that for many, their deafness is not viewed as a deficit but as a characteristic that has shaped their unique perspective and fostered a rich cultural heritage.

This identity is a source of pride and a defining aspect of their social and personal lives.

“The Deaf community is a linguistic minority, not a disabled group.”

Understanding “Deaf” as an identity involves recognizing:

- Shared Experiences: Individuals who identify as Deaf often share common experiences related to growing up in a hearing-centric world, navigating communication barriers, and finding community within Deaf spaces.

- Cultural Membership: This identity signifies membership in a distinct cultural group with its own social norms, traditions, and a shared sense of belonging.

- Pride and Empowerment: For many, identifying as Deaf is a source of pride and empowerment, embracing their unique way of experiencing the world and communicating.

- Linguistic Minority Status: Deaf individuals are recognized as a linguistic minority, with sign language being their primary language, similar to other linguistic minorities worldwide.

The Role of Sign Language in Deaf Culture

Sign language is not merely a communication tool for Deaf individuals; it is the very bedrock upon which Deaf culture is built. It serves as the primary means of expression, connection, and the transmission of shared experiences, values, and history. Understanding sign language is fundamental to grasping the richness and complexity of Deaf identity.Sign languages are vibrant, natural languages that possess their own unique grammars, syntaxes, and vocabularies, independent of spoken languages.

They are visual-gestural languages, utilizing handshapes, movements, facial expressions, and body posture to convey meaning. The profound connection between sign language and Deaf culture means that the language is inextricably linked to the community’s sense of self and belonging.

Linguistic Diversity of Sign Languages

The world of sign languages is as diverse as the spoken languages of the globe. There is no universal sign language; instead, each country and often each region within a country has its own distinct sign language, shaped by its unique history, geography, and cultural influences. This linguistic diversity reflects the varied experiences and development of Deaf communities worldwide.To illustrate this diversity, consider the following:

- American Sign Language (ASL): Developed from a blend of French Sign Language (LSF) and indigenous sign languages used in the United States, ASL is used in the US and parts of Canada.

- British Sign Language (BSL): Distinct from ASL, BSL has a different historical lineage and is not mutually intelligible with ASL.

- Langue des Signes Française (LSF): The historical predecessor to ASL, LSF is used in France and other French-speaking regions.

- Auslan (Australian Sign Language): Developed from British Sign Language, Auslan is the primary sign language used in Australia.

The existence of these distinct sign languages underscores the importance of recognizing and respecting the linguistic autonomy of Deaf communities. Learning a specific sign language opens the door to understanding the culture and community that uses it.

Historical Development and Evolution of Prominent Sign Languages

The evolution of sign languages is a fascinating journey, often intertwined with the history of education for the Deaf. Many sign languages trace their origins back to the 19th century, with significant contributions from pioneering educators and the natural development within Deaf communities.

For example, the development of American Sign Language (ASL) is often attributed to the work of Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet and Laurent Clerc. Gallaudet traveled to Europe to study methods of educating the Deaf and met Clerc, a Deaf teacher from the Institut National de Jeunes Sourds de Paris. Clerc brought French Sign Language (LSF) with him to the United States in 1817.

In the burgeoning American Deaf community, LSF interacted with existing indigenous sign languages, leading to the formation and evolution of what we now know as ASL. This process of language contact and creolization is a common theme in the development of many sign languages.

The evolution is ongoing, with sign languages continually adapting to new concepts, technologies, and social changes. New signs are coined, existing signs are modified, and the language itself reflects the dynamic nature of the communities that use it.

Grammatical Structures of Spoken Languages versus Sign Languages

While both spoken and sign languages are fully developed linguistic systems, their grammatical structures differ significantly due to their modality. Spoken languages are auditory-sequential, relying on sound and order of words. Sign languages, being visual-gestural, utilize space, movement, and simultaneous expression of information.A key difference lies in the use of space. Sign languages employ spatial grammar, where the placement and movement of signs in the signing space can convey grammatical information such as tense, agreement, and directionality.

For instance, a verb might be signed from one location to another to indicate the subject and object.Consider these comparisons:

- Word Order: While spoken languages often have strict word orders (e.g., Subject-Verb-Object), sign languages can be more flexible, with meaning conveyed through a combination of signs and non-manual markers (facial expressions, head tilts, body shifts).

- Iconicity: Many signs are iconic, meaning they visually resemble the object or action they represent. However, iconicity is not the sole basis of sign language; many signs are abstract and arbitrary, just like words in spoken languages.

- Simultaneity: Sign languages can convey multiple pieces of information simultaneously. For example, a single sign can incorporate information about the action, the manner of the action, and the subject/object through handshape, movement, and non-manual signals.

“Sign languages are not pantomime or a simplified version of spoken languages; they are complex, natural languages with their own distinct grammatical rules and structures.”

Sign Language Facilitating Social Interaction and Knowledge Transmission

Sign language is the primary vehicle for social interaction within the Deaf community. It enables Deaf individuals to form strong bonds, share experiences, and build a collective identity. Beyond casual conversation, sign language is crucial for the transmission of cultural knowledge, history, and values from one generation to the next.Through storytelling, poetry, theatre, and informal discussions, Deaf individuals pass down their heritage and traditions.

Educational settings, when conducted in sign language, ensure that Deaf students receive information in their native linguistic modality, fostering deeper understanding and engagement.The importance of sign language in this context can be seen in:

- Community Cohesion: Shared sign language creates a powerful sense of belonging and solidarity among Deaf individuals, fostering a supportive social network.

- Cultural Preservation: Sign language is the repository of Deaf history, folklore, and artistic expression, ensuring the continuity of Deaf culture.

- Educational Equity: When sign language is used as the medium of instruction, it provides Deaf students with equal access to education and empowers them to achieve their full potential.

- Intergenerational Knowledge Transfer: Older Deaf individuals, fluent in sign language, serve as vital links to the past, sharing stories and wisdom with younger generations.

The ability to communicate fluently in sign language is therefore not just a practical skill but a gateway to full participation in Deaf culture and society.

Socialization and Community within Deaf Culture

The integration into Deaf culture is a multifaceted process, deeply rooted in shared experiences, communication, and a strong sense of belonging. For many, becoming part of the Deaf community is a journey that begins with recognizing their Deaf identity and actively seeking connections with others who share similar life experiences. This process often involves learning about Deaf history, values, and social norms, which are crucial for fostering a robust and vibrant community.The socialization within Deaf culture is characterized by intentional efforts to build and maintain connections.

This is achieved through various avenues, all designed to foster mutual understanding, support, and a shared identity. The emphasis is on creating spaces where Deaf individuals can thrive, communicate freely, and engage in activities that are meaningful to them.

Integration into Deaf Communities

Individuals typically become integrated into Deaf communities through a combination of personal discovery, educational experiences, and active participation in social events. Early exposure to Deaf culture, often through family members or mentors, can provide a foundational understanding and a sense of belonging. For those who become Deaf later in life or are newly introduced to the culture, the process involves seeking out resources and opportunities to connect.The integration process often includes:

- Family and Relational Ties: Many individuals are born into Deaf families, inheriting a strong connection to the culture from birth.

- Educational Settings: Attending Deaf schools or programs within mainstream schools provides a crucial environment for socialization and learning.

- Community Organizations: Joining Deaf clubs, associations, and advocacy groups offers structured opportunities for interaction and involvement.

- Social Gatherings: Participating in informal meetups, parties, and cultural events is a primary way to build relationships and experience Deaf community life.

- Online Platforms: The digital age has introduced online forums, social media groups, and video conferencing as vital tools for connection and information sharing.

The Importance of Deaf Schools and Social Gatherings

Deaf schools and social gatherings are cornerstones of Deaf culture, serving as vital hubs for socialization, education, and the transmission of cultural norms. These environments provide unparalleled opportunities for Deaf individuals to interact with peers who share similar communication methods and life experiences, fostering a strong sense of identity and belonging.Deaf schools are more than just educational institutions; they are incubators of Deaf culture.

Within these schools, students learn not only academic subjects but also the nuances of Deaf communication, social etiquette, and the history and values of the Deaf community. This shared educational experience creates lifelong bonds and a deep understanding of collective identity.Social gatherings, ranging from informal coffee meetups to larger cultural festivals and events, are equally critical. They provide a relaxed and inclusive atmosphere where individuals can connect, share stories, and reinforce their cultural ties.

These events are essential for maintaining the vibrancy and continuity of the Deaf community.

Forms of Artistic Expression and Entertainment

Deaf culture boasts a rich tapestry of artistic expression and entertainment that is intrinsically linked to its visual and tactile nature. These art forms not only provide enjoyment but also serve as powerful vehicles for storytelling, cultural preservation, and social commentary. The creativity within the Deaf community is a testament to its resilience and unique perspective.Common forms of artistic expression and entertainment include:

- Visual Arts: Painting, drawing, sculpture, and photography often explore themes of Deaf identity, history, and societal experiences.

- Performance Arts: This encompasses signed storytelling, theatrical performances that utilize sign language, and expressive dance.

- Literature and Poetry: Deaf poets and writers create works that are deeply rooted in visual language and cultural narratives, often performed in sign language.

- Film and Video: The creation of films and videos in sign language has grown significantly, offering a powerful medium for storytelling and cultural dissemination.

- Deaf Humor: A distinct form of humor often relies on visual gags, wordplay specific to sign language, and shared cultural references.

Scenario: A Typical Social Interaction at a Deaf Event

Imagine a Deaf community picnic held in a local park on a sunny Saturday afternoon. Tables are set up with food, and a designated area is open for mingling. A Deaf individual named Anya, who recently moved to the area, arrives and looks around, a mix of anticipation and slight nervousness on her face.She spots a group of people signing animatedly near a large oak tree.

Approaching them, she catches the eye of a woman named Maria, who offers a warm, open-handed wave and a welcoming smile. Maria signs, “Welcome! Have you been to our picnics before?” Anya signs back, “No, this is my first time. I just moved here.”Another person in the group, David, joins the conversation, signing, “Great to have you! I’m David. This is Maria, and that’s Ben over there.” He gestures towards a man engrossed in a conversation with another individual.

Maria adds, “We’re just discussing the upcoming Deaf film festival. Have you seen any of the films yet?” Anya expresses her excitement about the festival, and the conversation flows easily, filled with laughter and shared nods of understanding. They discuss their favorite sign language poets and the best local coffee shops that are Deaf-friendly. As more people arrive, they are warmly included in the existing conversations, making Anya feel instantly welcomed and connected.

The interaction is characterized by direct eye contact, expressive facial grammar, and a palpable sense of camaraderie, illustrating the inclusive and supportive nature of Deaf social gatherings.

Communication Styles and Etiquette

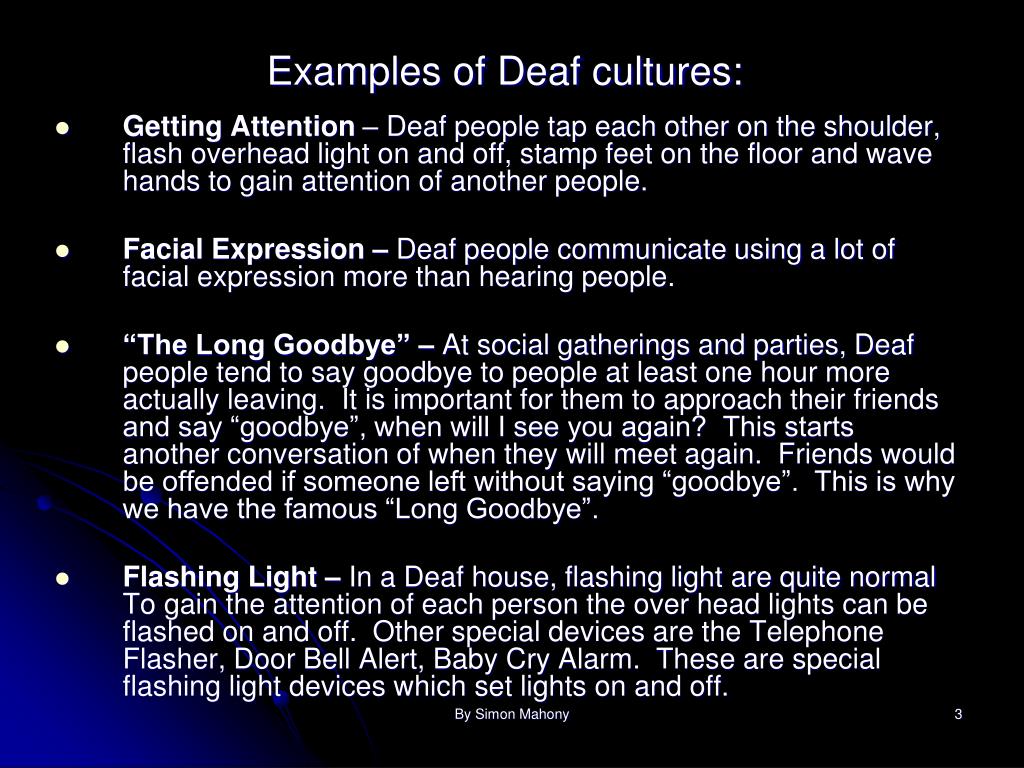

Understanding the preferred communication methods and etiquette within Deaf culture is fundamental to fostering respectful and effective interactions. These practices are deeply intertwined with the visual nature of sign language and the shared experiences of the Deaf community. By observing and adhering to these norms, hearing individuals can significantly enhance their communication with Deaf individuals.The way conversations are initiated, maintained, and concluded in Deaf culture often differs from hearing-centric norms.

These differences are not arbitrary but are rooted in practical considerations for visual communication and a strong sense of community.

Preferred Communication Methods and Etiquette

Deaf individuals generally prefer communication methods that are visual and readily accessible. This often includes sign language, but also encompasses other visual aids and strategies. Etiquette emphasizes clarity, directness, and mutual respect for the communication process.The following are key aspects of preferred communication methods and etiquette:

- Sign Language Proficiency: For Deaf individuals who use sign language, this is the primary and most preferred mode of communication. Fluency in a specific sign language, such as American Sign Language (ASL) or British Sign Language (BSL), allows for the full expression of nuances, emotions, and complex ideas.

- Visual Aids: When sign language is not fully accessible to all parties, visual aids such as writing notes, using gestures, drawing, or utilizing text-based communication apps are commonly employed. The key is to ensure information is conveyed visually.

- Patience and Understanding: Communication can take more time and effort, especially when there are language barriers. Patience from all participants is crucial for a successful exchange.

- Directness: Communication tends to be more direct. This is not considered rude but rather efficient for visual communication, where beating around the bush can lead to misunderstandings.

- Eye Contact: Sustained eye contact is essential. It signifies attention, engagement, and understanding. Looking away for extended periods can be interpreted as disinterest or a lack of comprehension.

The Importance of Visual Attention

Visual attention is the cornerstone of communication within Deaf culture. Because sign language is a visual-gestural language, maintaining visual contact is paramount for receiving and understanding information. It is not merely about seeing, but about actively processing visual cues.This concept is critical for several reasons:

- Receiving Information: Sign language is perceived through the eyes. Without sustained visual attention, the signs, facial expressions, and body language that convey meaning will be missed.

- Signaling Engagement: Maintaining eye contact signals that one is actively listening and engaged in the conversation. It is a sign of respect and attentiveness.

- Understanding Nuance: Facial expressions and body language are integral parts of sign language, conveying grammatical information, tone, and emotion. These are only observable when visual attention is maintained.

For hearing individuals, it is important to be aware that if you are not maintaining eye contact, the Deaf person may believe you are not paying attention or are not understanding.

Initiating Communication with Hearing Individuals

Approaching and initiating communication with a Deaf individual requires awareness and sensitivity. The goal is to get their attention in a way that is effective and respectful of their visual field.Appropriate methods for initiating communication include:

- Gentle Tapping: A gentle tap on the shoulder or upper arm is a common and effective way to get a Deaf person’s attention without startling them.

- Waving: Waving your hand within their field of vision is another polite way to signal your presence and desire to communicate.

- Flashing Lights: In environments where visual cues are limited or there is ambient noise, flickering lights (e.g., turning lights on and off) can be used to attract attention.

- Getting Closer: If possible, moving closer to the Deaf person so they can see you is a direct way to initiate contact.

- Making Yourself Visible: Ensure you are in their line of sight before attempting to communicate.

It is generally advised to avoid sudden movements or loud noises, as these can be startling and disruptive to someone who relies heavily on visual cues.

Turn-Taking and Conversational Flow in Sign Language

Conversational flow in sign language has its own unique rhythm and structure, which differs from spoken conversations. Turn-taking is managed visually, with clear cues that indicate when one person is finished speaking and the other can begin.Key aspects of turn-taking and conversational flow include:

- Visual Cues for Turn-Taking: A signer may indicate the end of their turn by pausing, lowering their hands, or making a specific grammatical marker. The other person will then begin signing.

- Simultaneous Signing (When Appropriate): In some informal settings, there might be brief moments of overlap where one person begins signing as the other finishes, similar to interruptions in spoken conversation, but this is typically understood and managed visually.

- Maintaining Visual Flow: The conversation continues as long as visual attention is maintained by all participants. If someone breaks eye contact for too long, the flow can be disrupted.

- Facial Expressions and Body Language: These are not just for conveying emotion but also for grammatical purposes and to indicate pauses, questions, and the end of a thought, all of which contribute to the flow.

- “Back-channeling” Equivalents: In spoken language, “uh-huh” or nodding can indicate listening. In sign language, subtle head nods, facial expressions, or brief signs like “YES” or “UNDERSTAND” can serve a similar purpose without interrupting the speaker’s flow.

Understanding these dynamics helps in participating more smoothly and respectfully in conversations with Deaf individuals, ensuring that the communication is not only heard (or seen) but also understood and appreciated.

Historical Context and Advocacy in Deaf Culture

Understanding Deaf culture necessitates an exploration of its rich history, marked by significant milestones in the fight for recognition, rights, and the development of unique cultural practices. This historical journey has been shaped by influential individuals and pivotal movements that have profoundly impacted the Deaf community and its ongoing pursuit of accessibility and inclusion.The evolution of Deaf culture is a testament to resilience and the unwavering spirit of advocacy.

From early educational efforts to the modern-day fight for linguistic rights and full societal integration, key moments and figures have consistently pushed the boundaries of understanding and acceptance.

Key Historical Milestones in Deaf Recognition

The path to recognizing Deaf culture as a distinct and valuable entity has been long and often challenging. Early efforts focused on education, with varying philosophies and outcomes shaping the community’s development.

- 1760: Abbé Charles-Michel de l’Épée establishes the first public school for the deaf in Paris. This marked a significant step in providing formal education and fostering a sense of community among Deaf individuals, utilizing early forms of sign language.

- 1817: Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet, with Laurent Clerc, founds the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut. This event was crucial in establishing formal education for the Deaf in the United States and introduced French Sign Language, which significantly influenced American Sign Language (ASL).

- 1864: The National Deaf-Mute College (now Gallaudet University) is chartered by Congress. This was a monumental achievement, providing the first and only institution of higher learning for the Deaf in the world, fostering leadership and academic advancement within the community.

- 1880: The Milan Congress passes a resolution banning oralism in schools for the deaf. This decision, heavily influenced by oralist proponents who believed in teaching Deaf students to speak and lip-read, led to a widespread suppression of sign language in education for decades, causing significant cultural disruption.

- 1960s: The development and widespread adoption of American Sign Language (ASL) as a recognized language. Linguistic research, particularly by William Stokoe, demonstrated that ASL is a complex, fully developed language with its own grammar and syntax, not merely gestures. This validation was crucial for the cultural and linguistic identity of the Deaf community.

- 1972: The first Deaf Awareness Week is proclaimed in the United States. This marked a growing public recognition of Deaf issues and culture, encouraging broader understanding and dialogue.

Influential Figures and Movements in Deaf Rights

Throughout history, certain individuals and collective movements have been instrumental in championing the rights and cultural identity of Deaf people. Their efforts have paved the way for greater accessibility and a more inclusive society.

- Laurent Clerc: A Deaf teacher from France, Clerc was a pivotal figure in the establishment of Deaf education in America. His collaboration with Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet and his profound influence on the development of ASL cannot be overstated.

- William Stokoe: A hearing linguist whose groundbreaking research in the 1960s proved that ASL is a true language, not a simplified form of English or mere pantomime. His work legitimized ASL and significantly boosted Deaf pride and cultural identity.

- The Deaf President Now (DPN) movement (1988): This student-led protest at Gallaudet University was a watershed moment. Students demanded the appointment of a Deaf president, successfully highlighting the capabilities of Deaf individuals and demanding representation. The protest involved widespread demonstrations, media attention, and ultimately led to the appointment of Dr. I. King Jordan as the university’s first Deaf president.

- The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 (Section 504): This landmark legislation prohibited discrimination on the basis of disability in any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance. It has been a critical tool for advocating for accessibility in education, employment, and public services for Deaf individuals.

Ongoing Advocacy for Accessibility and Inclusion

The fight for full accessibility and inclusion is a continuous process. Contemporary advocacy efforts focus on a wide range of issues, from technological advancements to legal protections and societal attitudes.

- Legal and Policy Advocacy: Organizations like the National Association of the Deaf (NAD) and the World Federation of the Deaf (WFD) actively lobby for stronger legal protections, including improved captioning requirements, access to interpreters, and the recognition of sign languages in legal and governmental proceedings.

- Technological Advancements: Advocacy extends to ensuring that new technologies are accessible. This includes pushing for better video relay services (VRS), real-time captioning on streaming platforms, and the development of assistive listening devices. For instance, the widespread availability of closed captioning on television and online content has dramatically increased access to information and entertainment for Deaf and hard-of-hearing individuals.

- Educational Reform: While progress has been made, advocacy continues to push for fully bilingual-bicultural education for Deaf children, where both sign language and written/spoken language are valued and taught effectively. This aims to counter the historical dominance of oralist approaches that have sometimes hindered language acquisition.

- Deaf Representation in Media and Society: There is an ongoing effort to increase positive and authentic representation of Deaf individuals in media, leadership roles, and all sectors of society. This challenges stereotypes and promotes a more accurate understanding of Deaf capabilities and culture.

Timeline of Significant Events in Deaf History

This timeline provides a concise overview of pivotal moments that have shaped Deaf culture and the advocacy for Deaf rights.

- 1760: Abbé Charles-Michel de l’Épée founds the first public school for the deaf in Paris.

- 1817: Thomas Hopkins Gallaudet and Laurent Clerc establish the American School for the Deaf in Hartford, Connecticut.

- 1843: The first Deaf teacher training program is established at the American School for the Deaf.

- 1864: The National Deaf-Mute College (now Gallaudet University) is chartered.

- 1880: The Milan Congress promotes oralism and leads to the suppression of sign language in many schools.

- 1906: The American Association to Promote the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf (now the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing) is founded, advocating for oral education.

- 1910: The National Association of the Deaf (NAD) is founded, becoming a leading voice for Deaf civil rights.

- 1964: The Telecommunications Act of 1964 includes provisions for deaf telecommunications access, a precursor to relay services.

- 1965: William Stokoe publishes his seminal work, “Sign Language Structure of Emotion,” validating ASL as a true language.

- 1972: The first Deaf Awareness Week is proclaimed in the United States.

- 1973: Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act is enacted, prohibiting discrimination based on disability.

- 1988: The Deaf President Now (DPN) protest at Gallaudet University leads to the appointment of a Deaf president.

- 1990: The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) is signed into law, providing broad civil rights protections for individuals with disabilities, including access to communication.

- 2010: The 21st Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act (CVAA) is passed, updating accessibility requirements for modern telecommunications.

Understanding Deafhood and Identity

Understanding Deafhood and identity delves into the deeply personal and cultural experiences of being Deaf. It moves beyond a purely audiological definition to encompass a rich tapestry of lived experiences, shared values, and a profound sense of belonging within a cultural group. This concept acknowledges that Deafness is not merely a medical condition but a fundamental aspect of self and community.Deafhood is best understood as a journey of self-discovery and cultural immersion.

It is the process by which an individual, typically born deaf or who becomes deaf, comes to embrace their Deaf identity, often through engagement with the Deaf community and its culture. This journey involves recognizing the shared history, language, and social norms that bind Deaf individuals together. It is a state of being, a cultural affiliation, and a perspective on the world that is shaped by the absence of hearing and the presence of a vibrant Deaf culture.

The Spectrum of Deaf Identities

Deaf identities are not monolithic; they exist on a broad spectrum, reflecting the diverse experiences and choices of individuals within the Deaf community. These identities are expressed through various means, including language preference, engagement with Deaf culture, and personal philosophy.

- Cultural Deaf: Individuals who identify strongly with Deaf culture, often fluent in sign language, and actively participate in Deaf community events and social circles.

- Oral Deaf: Individuals who primarily use spoken language for communication and may not have strong ties to Deaf culture or sign language.

- Late-Deafened: Individuals who lose their hearing later in life. Their identity may be a blend of their hearing experiences and their adjustment to deafness, often involving learning sign language and connecting with the Deaf community.

- Deaf-Blind: Individuals who have both hearing and visual impairments, requiring specialized communication methods and often forming unique communities within the broader Deaf and disability spheres.

- Interpreters and Allies: While not Deaf themselves, individuals who work closely with the Deaf community, such as sign language interpreters, can develop a deep understanding and appreciation for Deaf culture, sometimes identifying as allies with a strong connection to the community.

Congenital vs. Acquired Deafness Experiences

The path to Deaf identity can differ significantly based on whether an individual is born deaf or acquires deafness later in life. These distinct origins shape their initial understanding of the world and their integration into Deaf culture.

- Congenitally Deaf Individuals: Those born deaf often grow up within families where Deafness is a known factor, or they may be identified early and enter educational settings with a strong Deaf presence. Their primary language is often sign language, and their immersion in Deaf culture from a young age fosters a natural and deep-rooted sense of identity. They may not have direct memories or experiences of a hearing world, making Deafness their primary frame of reference.

- Acquired Deafness Later in Life: Individuals who become deaf later in life often experience a period of adjustment and grief for their lost hearing. Their prior experiences in the hearing world can influence their identity, and they may grapple with integrating their hearing past with their Deaf present. Learning sign language and connecting with the Deaf community can be a deliberate and transformative process, leading to a unique perspective that bridges both worlds.

A Framework for Understanding Deaf Identity

Understanding the multifaceted nature of Deaf identity requires a framework that acknowledges its complexity and individuality. This framework can be visualized as a series of interconnected dimensions, each contributing to an individual’s sense of self.

| Dimension | Description | Expression |

|---|---|---|

| Linguistic Identity | The role and proficiency of sign language and/or spoken language in an individual’s life. | Fluency in ASL, BSL, or other sign languages; use of spoken language; preference for visual communication. |

| Cultural Affiliation | The degree of connection and participation in Deaf community norms, values, and social activities. | Attending Deaf events, understanding Deaf humor, respecting Deaf traditions, identifying with Deaf history. |

| Audiological Status | The degree of hearing loss and the audiological characteristics. | Mild to profound hearing loss; use of hearing aids or cochlear implants (though this does not preclude a Deaf identity). |

| Social Connection | The extent of engagement with both Deaf and hearing social circles. | Strong ties within the Deaf community; relationships with hearing family and friends; advocacy roles. |

| Personal Experience | Individual life journey, including upbringing, education, and personal choices regarding identity. | Family background (Deaf parents, hearing parents), educational experiences (Deaf school, mainstream school), personal realization of Deaf identity. |

This framework highlights that Deaf identity is not a fixed point but a dynamic and evolving aspect of self, influenced by a confluence of personal, social, and cultural factors.

Audiological Considerations and Perceptions

Understanding audiological considerations is crucial for a comprehensive grasp of Deaf culture. It moves beyond a singular definition of “Deaf” to acknowledge the spectrum of hearing abilities and the diverse ways individuals experience and interact with sound. This section explores these nuances, highlighting how they shape identity and community within the Deaf world.The Deaf community is not a monolithic entity defined solely by the absence of hearing.

Instead, it encompasses a wide range of audiological profiles and perspectives on hearing technology. These differences significantly influence individual experiences, cultural viewpoints, and the ongoing dialogue surrounding deafness.

Range of Hearing Abilities within the Deaf Community

The term “Deaf” is often used as an umbrella term, but it encompasses individuals with varying degrees of hearing loss. This spectrum is important to recognize, as it impacts communication preferences, social interactions, and identity formation.

- Profoundly Deaf: Individuals with severe to profound hearing loss, often experiencing little to no functional hearing.

- Hard of Hearing: Individuals with mild to moderate hearing loss who may benefit from hearing aids or other assistive listening devices.

- Late-Deafened Adults: Individuals who acquired significant hearing loss later in life and may retain memories of sound and spoken language.

- Deafblind: Individuals who have both a significant hearing loss and a significant vision loss.

Perspectives on Hearing Aids and Cochlear Implants

Within Deaf culture, there is a diversity of opinions regarding the use of hearing aids and cochlear implants. These perspectives are often rooted in cultural identity, personal experience, and philosophical beliefs about deafness.

- Cultural Deafness Perspective: Many within the culturally Deaf community view deafness as an identity and a culture, rather than a disability to be fixed. From this viewpoint, hearing aids and cochlear implants may be seen as attempts to assimilate into the hearing world and erase Deaf identity. The focus is on celebrating Deaf culture and communication, often through sign language, rather than striving for auditory “normalcy.”

- Medical/Rehabilitative Perspective: Others, particularly those who are hard of hearing or late-deafened, may embrace hearing aids and cochlear implants as tools to enhance their connection to the hearing world and improve their quality of life. This perspective often aligns with a medical model that seeks to mitigate the effects of hearing loss.

- Personal Choice and Nuance: It is important to note that many individuals navigate these perspectives with personal choice and nuance. Some may use hearing aids for specific situations while still identifying strongly with Deaf culture, while others may choose not to use them for personal or cultural reasons. The decision is deeply personal and influenced by individual circumstances and values.

Comparison of the Medical Model of Deafness with the Cultural Model

The way deafness is understood has evolved significantly, with two primary models offering contrasting viewpoints: the medical model and the cultural model. These models shape how deafness is perceived by society and by individuals within the Deaf community.

The medical model views deafness as a deficiency or pathology that needs to be cured or remediated.

This model often focuses on the audiological aspects of hearing loss and aims to restore hearing or improve communication through technological interventions like hearing aids and cochlear implants. The goal is often to enable individuals to function within the hearing world.

The cultural model, conversely, views deafness not as a disability, but as a linguistic and cultural identity.

This perspective emphasizes the unique experiences, values, and community of Deaf people, with sign language serving as a central pillar. It recognizes that Deaf individuals have their own rich culture, social norms, and ways of being in the world, and it advocates for accessibility and acceptance rather than for “fixing” deafness.

Perceptions and Navigation of the Hearing World by Deaf Individuals

Deaf individuals develop unique strategies and perspectives for navigating a world primarily designed for hearing people. This navigation often involves a keen awareness of visual cues, a reliance on communication accessibility, and a conscious effort to bridge the gap between Deaf and hearing environments.

- Visual Acuity and Environmental Awareness: Many Deaf individuals develop heightened visual awareness, becoming adept at observing body language, facial expressions, and environmental cues that hearing people might overlook. This serves as a vital tool for understanding social dynamics and anticipating communication needs.

- Proactive Communication Strategies: Navigating the hearing world often requires Deaf individuals to be proactive in ensuring communication is understood. This can involve:

- Clearly indicating their communication preferences (e.g., “I am Deaf, please face me and speak clearly”).

- Using visual aids or writing when necessary.

- Seeking out accessible environments or individuals.

- Learning to lip-read, though this is a skill that varies greatly in effectiveness among individuals and is not a universal expectation.

- Awareness of Accessibility Barriers: Deaf individuals are often acutely aware of the accessibility barriers they encounter in everyday life, from public announcements and customer service interactions to educational settings and social gatherings. This awareness can lead to frustration but also to a strong drive for advocacy and change.

- Code-Switching and Identity Management: Some Deaf individuals may engage in “code-switching,” adapting their communication style or behavior depending on whether they are interacting within the Deaf community or the hearing world. This can be a strategy for managing their identity and ensuring effective communication in different contexts.

Visual Storytelling and Art Forms

Deaf culture possesses a profoundly rich and vibrant tradition of visual storytelling, deeply rooted in the inherent strengths of visual communication. This tradition manifests across a diverse array of artistic expressions, allowing for the nuanced and powerful conveyance of experiences, emotions, and narratives. The visual nature of sign language naturally lends itself to artistic interpretation, making visual arts a cornerstone of Deaf cultural expression.The visual arts within Deaf culture are not merely decorative; they serve as vital conduits for cultural preservation, identity affirmation, and social commentary.

Artists often draw inspiration from their lived experiences, the history of the Deaf community, and the unique aspects of visual communication, creating works that resonate deeply within the culture and offer profound insights to the wider world.

The Rich Tradition of Visual Storytelling

Visual storytelling in Deaf culture leverages the inherent expressiveness of the hands, face, and body to create compelling narratives. This form of storytelling transcends simple description, often incorporating emotional depth, symbolic representation, and a unique rhythm that is deeply understood by Deaf audiences. It is a dynamic and engaging way to share history, personal anecdotes, and cultural values, ensuring their continuity and evolution.

Deaf Artists and Their Contributions

The contributions of Deaf artists to various art forms are significant and continue to grow. These artists, working across painting, sculpture, photography, digital art, and performance, bring unique perspectives shaped by their visual experiences and cultural understanding.

- Chuck Baird (1947-2012): A highly influential painter and storyteller, Baird is renowned for his vibrant and expressive depictions of Deaf life, culture, and sign language. His work often captures the essence of signing conversations and the emotional nuances of the Deaf experience.

- N. G. Pyle: A contemporary Deaf artist whose work explores themes of identity, language, and belonging through mixed media and abstract forms.

- Christine Sun Kim: Known for her performance art, drawings, and installations, Kim investigates the social and cultural aspects of sound and silence, often from a Deaf perspective. Her work challenges conventional notions of communication and perception.

- Ann Silver: A prolific artist whose work often features bold graphics and humor, exploring Deaf identity and the visual aspects of sign language. She has significantly contributed to the visibility of Deaf art.

Mime, Poetry, and Theater as Expressive Mediums

Mime, poetry, and theater are powerful expressive mediums within Deaf culture, allowing for the exploration of complex emotions and narratives through purely visual means. These art forms often utilize exaggerated physicality, facial expressions, and the creative manipulation of space to convey meaning.

- Mime: While not exclusive to Deaf culture, mime is a highly developed art form for Deaf performers, allowing for universal understanding through physical action and expression. It is often used to tell stories, evoke emotions, and create vivid imagery without spoken words.

- Deaf Poetry: Visual poetry, or “signed poetry,” is a performance art where poems are recited in sign language. It emphasizes the visual aesthetics of signs, the rhythm of the signing, and the performer’s expressive delivery to create a powerful and moving experience.

- Deaf Theater: This encompasses a wide range of theatrical productions, from classic plays performed in sign language with interpreters to original works created by Deaf playwrights and actors. Deaf theater often highlights the unique communication styles and cultural perspectives of the Deaf community, offering innovative storytelling approaches.

A Descriptive Narrative of a Visual Performance

Imagine a stage bathed in soft, shifting light. A single performer, a Deaf artist, stands center stage. The narrative begins not with words, but with a gesture – a sweeping arc of the hand that conjures a vast, open sky. The performer’s eyes widen, conveying awe, and their body leans back as if gazing at an immense expanse. Then, the hands begin to move with incredible speed and precision, fingers intertwining and separating to depict the flight of birds, their movements fluid and graceful, mirroring the unseen currents of the air.A subtle shift in the performer’s posture, a slight furrowing of the brow, and the mood changes.

The hands now move with a grounded, deliberate energy, forming the shape of a sturdy house. The facial expression conveys a sense of warmth and security. The performer’s hands then begin to weave a tale of a family within those walls, their fingers becoming distinct characters, interacting with subtle nods, glances, and playful gestures. A moment of playful banter is depicted through quick, sharp movements and twinkling eyes, followed by a scene of quiet contemplation, where the performer’s hands rest gently, their gaze thoughtful, suggesting a shared understanding that needs no words.The performance culminates with a powerful visual metaphor: the performer slowly brings their hands together, palms facing, then gently pushes them apart, symbolizing the creation of something new, a burgeoning idea, or a profound connection.

The final image is one of radiant energy, conveyed through the expansive reach of the arms and a serene, confident smile, leaving the audience with a profound sense of shared humanity and the boundless potential of visual expression.

Last Word

In essence, grasping the basics of Deaf culture reveals a profound tapestry woven from shared language, community bonds, historical resilience, and a unique worldview. It’s a culture that celebrates visual expression, cherishes communal identity, and actively advocates for recognition and inclusion. By understanding these core components, we gain a deeper appreciation for the richness and diversity of human experience, fostering a more inclusive and empathetic society for all.