Beginning with How to Understand the Difference Between “Deaf” and “deaf”, the narrative unfolds in a compelling and distinctive manner, drawing readers into a story that promises to be both engaging and uniquely memorable.

Capitalization in English is more than just a stylistic choice; it profoundly influences meaning and tone. This distinction is particularly significant when discussing identity and audiological experiences, as the difference between “Deaf” with a capital ‘D’ and “deaf” with a lowercase ‘d’ carries substantial weight in conveying respect and understanding.

The “Deaf” (Uppercase D) Identity and Culture

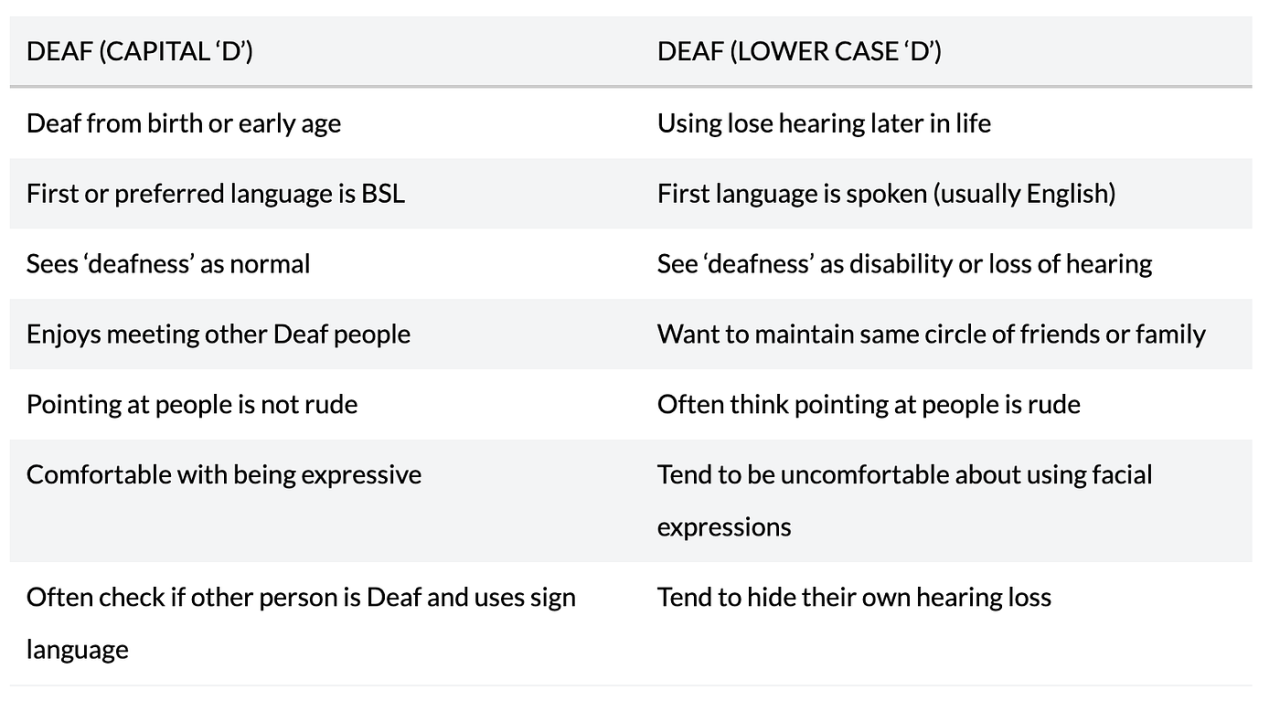

The designation of “Deaf” with a capital ‘D’ signifies a profound connection to a shared identity, culture, and community. It moves beyond a mere audiological description to encompass a rich social and cultural experience. Understanding “Deaf” as an identity is crucial for appreciating the multifaceted lives of individuals within this community.The concept of Deaf culture is a vibrant and integral aspect of this identity.

It is characterized by a unique set of beliefs, values, social behaviors, and traditions that have been developed and passed down through generations within the Deaf community. This culture provides a sense of belonging, pride, and a framework for understanding the world.

Defining Characteristics of Deaf Culture

Deaf culture is not defined by the absence of hearing, but rather by the presence of a shared linguistic and cultural heritage. This heritage is deeply intertwined with the use of sign language, which serves as the primary mode of communication and a cornerstone of Deaf identity. The visual nature of sign language shapes communication styles, social interactions, and artistic expressions.Common elements of Deaf community life and shared experiences are numerous and contribute to a strong sense of solidarity.

These include:

- Sign Language: The use of a visual-gestural language, such as American Sign Language (ASL), British Sign Language (BSL), or other national sign languages, is fundamental. Sign language is not just a communication tool but a repository of cultural knowledge and identity.

- Shared History and Experiences: A collective history, often marked by struggles for access, recognition, and rights, binds the community. Shared experiences in navigating a predominantly hearing world foster mutual understanding and support.

- Artistic and Literary Traditions: Deaf culture boasts rich artistic traditions, including Deaf poetry, storytelling, theater, and visual arts, all of which often incorporate visual elements and themes relevant to Deaf experiences.

- Social Norms and Etiquette: Specific social norms and etiquette exist within the Deaf community, such as visual attention-getting methods (e.g., waving hands, tapping on a surface) and the importance of direct eye contact during communication.

- Educational Institutions and Organizations: Residential schools for the Deaf have historically played a pivotal role in fostering Deaf culture and community by bringing deaf children together and providing education in sign language. Many Deaf organizations continue to advocate for the rights and well-being of the community.

“Deaf” as a Collective Identity

The use of “Deaf” with a capital ‘D’ is a deliberate choice to represent a collective, shared identity. It signifies an affiliation with a linguistic and cultural minority group, rather than solely a medical condition. This capitalization asserts pride in one’s identity and acknowledges the existence and validity of Deaf culture.Examples of how “Deaf” is used to refer to a collective, shared identity include:

- Referring to “Deaf schools” which are institutions that have historically served as centers for Deaf culture and community development.

- Discussing “Deaf history” which highlights the struggles and triumphs of Deaf people throughout time.

- Acknowledging “Deaf rights” which pertains to the advocacy for equal access and recognition of the Deaf community’s linguistic and cultural needs.

- Speaking of “Deaf leaders” who are individuals who have significantly contributed to the advancement and empowerment of the Deaf community.

- Mentioning “Deaf events” such as conferences, festivals, and social gatherings that bring members of the Deaf community together.

The capitalization of “Deaf” is a powerful affirmation of belonging to a distinct cultural and linguistic group.

The “deaf” (Lowercase d) Audiological and Medical Perspective

While the capital “D” in “Deaf” signifies a cultural identity, the lowercase “d” in “deaf” points to a more clinical and audiological understanding of hearing status. This perspective focuses on the physiological ability to hear and the medical implications of hearing loss. It is a descriptive term used within healthcare and audiology to categorize individuals based on their auditory functioning.The audiological definition of “deaf” (lowercase d) refers to a severe to profound hearing loss, where an individual has significant difficulty understanding speech even with amplification.

This is a medical classification based on measurable hearing thresholds and the degree to which sound can be perceived. It is important to understand that this definition is distinct from the cultural and social aspects encompassed by the term “Deaf.”

Audiological Definition of Hearing Loss

Audiology uses specific measurements to quantify hearing ability. Hearing loss is typically categorized by its degree, ranging from mild to profound, based on the decibel (dB) level of the softest sound an individual can hear at different frequencies. This classification helps in determining the appropriate interventions and assistive devices.The typical language used when discussing hearing status in a medical or technical context often involves precise terminology related to audiological assessments and diagnostic findings.

This language aims for clarity and objectivity in describing an individual’s hearing capabilities.

- Normal Hearing: Typically defined as the ability to hear sounds up to 20 dB HL (Hearing Level). Individuals with normal hearing can usually understand conversational speech without difficulty.

- Mild Hearing Loss: A hearing loss between 20 dB HL and 40 dB HL. This can make it difficult to hear soft sounds and may lead to missing parts of conversations, especially in noisy environments.

- Moderate Hearing Loss: A hearing loss between 40 dB HL and 55 dB HL. Speech sounds become significantly softer, and understanding conversation without amplification becomes challenging.

- Moderately Severe Hearing Loss: A hearing loss between 55 dB HL and 70 dB HL. Spoken language is generally not understood without a hearing aid.

- Severe Hearing Loss: A hearing loss between 70 dB HL and 90 dB HL. Even loud sounds may not be heard, and understanding speech is extremely difficult without powerful amplification or other assistive listening devices.

- Profound Hearing Loss: A hearing loss of 90 dB HL or greater. In this category, an individual may only hear very loud sounds, and speech is typically not perceived at all without significant intervention. This is often the audiological classification associated with the term “deaf” (lowercase d).

Comparison of Audiological and Cultural Definitions

The audiological definition of “deaf” (lowercase d) is a quantifiable measure of auditory function, while the cultural definition of “Deaf” (uppercase D) is a social and cultural construct. An individual can have a severe or profound hearing loss (audiological “deaf”) without identifying with the Deaf culture, and conversely, some individuals who are audiological “Deaf” may not fully engage with the cultural aspects of the Deaf community.

It is essential to recognize that these two definitions, while related to hearing, represent different aspects of an individual’s identity and experience:

- Audiological Perspective: Focuses on the physiological condition of hearing loss, measured in decibels and categorized by degree and type (e.g., conductive, sensorineural, mixed). This perspective is crucial for medical diagnosis, treatment, and the prescription of assistive listening devices like hearing aids and cochlear implants.

- Cultural Perspective: Encompasses shared values, beliefs, social norms, language (e.g., Sign Language), and a sense of community among individuals who identify as Deaf. This identity is often built on shared experiences and a collective understanding of the world.

Medical Perspective on Hearing Loss

From a medical standpoint, hearing loss is viewed as a condition that can be diagnosed, treated, and managed. Medical professionals, including otolaryngologists (ENT doctors) and audiologists, work to identify the cause of hearing loss, assess its severity, and recommend appropriate interventions.The medical perspective often considers the following aspects of hearing loss:

- Etiology: The underlying cause of the hearing loss, which can range from genetic factors, aging (presbycusis), infections, exposure to loud noise, certain medications, or physical trauma to the ear.

- Type of Hearing Loss:

- Conductive Hearing Loss: Occurs when sound waves are blocked from entering the outer or middle ear. This can often be treated medically or surgically.

- Sensorineural Hearing Loss: Results from damage to the inner ear or the auditory nerve. This type is usually permanent and is often managed with hearing aids or cochlear implants.

- Mixed Hearing Loss: A combination of both conductive and sensorineural hearing loss.

- Impact on Communication: The medical assessment also considers how the hearing loss affects an individual’s ability to communicate and their overall quality of life.

- Management and Rehabilitation: This includes the use of hearing aids, cochlear implants, assistive listening devices, speech therapy, and other audiological rehabilitation strategies.

“The audiological definition of ‘deaf’ (lowercase d) is rooted in the measurable degree of hearing impairment, typically referring to a significant loss of auditory acuity, whereas the cultural identity of ‘Deaf’ (uppercase D) is a self-defined, community-based affiliation.”

Nuances and Overlap in Usage

While the distinction between “Deaf” and “deaf” provides a valuable framework for understanding different perspectives within the hearing spectrum, it’s important to acknowledge that reality is often more fluid and complex. Individuals’ experiences and identities can exist on a spectrum, and the lines between audiological and cultural perspectives may not always be sharply defined.In many instances, individuals may find themselves identifying with aspects of both the audiological and cultural definitions.

For example, someone who has experienced hearing loss from a young age and uses sign language might also identify with the audiological reality of their hearing status. Conversely, someone who identifies with Deaf culture may still acknowledge the medical and audiological aspects of their hearing. This overlap highlights the personal and multifaceted nature of identity.

Situations with Less Clear Distinctions

The distinction between “Deaf” and “deaf” can become less clear in several situations, reflecting the diverse experiences within the hearing loss community.

- Late-Onset Hearing Loss: Individuals who experience significant hearing loss later in life may grapple with whether to adopt the “Deaf” identity. They might retain strong connections to the hearing world and its communication norms while also experiencing the audiological reality of deafness and potentially seeking out Deaf community resources.

- Bilingual/Bicultural Individuals: Some individuals are fluent in both spoken language and sign language and may move between hearing and Deaf communities. Their identity can be fluid, embracing aspects of both audiological understanding and cultural belonging depending on the context.

- Profound Hearing Loss with Limited Sign Language Use: A person with profound hearing loss who primarily uses spoken language and has not engaged with the Deaf community might identify with the audiological “deaf” but not necessarily the cultural “Deaf.” However, their audiological reality can still lead them to seek out specific services or accommodations.

- Family and Community Influence: The language and identity adopted by an individual can be heavily influenced by their family’s background and the communities they are part of. If their family is part of the Deaf community, they are more likely to embrace the “Deaf” identity, regardless of their specific audiological profile.

Embracing Dual Identities

It is entirely possible and common for an individual to identify with both the audiological reality of their hearing status and the rich cultural identity associated with being “Deaf.” This dual identification often stems from a lived experience that encompasses both the physiological aspects of hearing loss and the social, linguistic, and cultural elements of the Deaf community.For instance, a person born with a significant hearing impairment who learned sign language from a young age and grew up immersed in Deaf culture would likely identify as “Deaf.” Simultaneously, they are aware of the audiological and medical aspects of their hearing status, which might be documented by audiologists or medical professionals.

This awareness does not negate their cultural identity; rather, it adds another layer to their understanding of themselves. They might participate in audiological appointments while also attending Deaf events and using sign language as their primary mode of communication. This integration of audiological understanding and cultural affiliation is a testament to the complexity and richness of individual identity.

Respecting Preferred Terminology

The most crucial aspect when discussing or referring to individuals is to respect their preferred terminology. This principle is rooted in the understanding that identity is personal and self-defined. Forcing a label or assuming one’s identity based on audiological data or external perceptions can be invalidating and disrespectful.It is always best to ask an individual how they prefer to be identified or to observe the language they use themselves.

If someone consistently capitalizes “Deaf” when referring to themselves and their community, it indicates a cultural identification. If they use lowercase “deaf” or focus on the audiological aspects, it suggests a different emphasis. This respect fosters inclusivity and acknowledges the agency of individuals in defining who they are.

Scenarios of Misinterpretation

Failing to understand the distinction between “Deaf” and “deaf” can lead to significant misunderstandings, impacting communication, access, and social interactions. These misinterpretations can arise from assumptions made based on audiological profiles rather than personal identity.

- Scenario 1: Communication Breakdown at a Service Appointment

A person who identifies as “Deaf” and primarily uses American Sign Language (ASL) visits a medical clinic. The receptionist, assuming that “deaf” simply means “cannot hear well” and that spoken language is sufficient, provides information verbally without offering an ASL interpreter or other communication accommodations. The Deaf individual struggles to understand, leading to frustration and potential medical errors. This misinterpretation overlooks the cultural and linguistic needs of the Deaf individual. - Scenario 2: Exclusion from Community Events

An individual who is audibly “deaf” (has hearing loss) but identifies with the “Deaf” culture and community attends a social gathering advertised for “Deaf” people. However, the event primarily focuses on spoken language discussions and offers no sign language interpretation or deaf-friendly communication strategies. The individual feels alienated and excluded, as their cultural identity was not recognized, and the event was not truly accessible to them. - Scenario 3: Inappropriate Medical Advice

A young person with profound hearing loss, who has grown up within the Deaf community and identifies as “Deaf,” is seeking audiological support. A medical professional, focusing solely on the audiological “deafness” and unaware of the cultural context, might push for specific hearing aid technologies or speech therapy without considering the individual’s existing communication fluency in sign language or their cultural preferences.This approach fails to acknowledge the individual’s holistic identity and potential communication strengths.

Demonstrating Understanding Through Examples

To solidify our understanding of the distinction between “Deaf” and “deaf,” it is beneficial to see these terms used in practical contexts. The following examples illustrate how capitalization conveys specific meanings related to identity, culture, and audiological status. By examining these examples, we can better appreciate the nuances and ensure respectful and accurate communication.

“Deaf” (Uppercase D) in Cultural and Identity Contexts

When referring to individuals who identify with the Deaf community and its associated culture, the uppercase “D” in “Deaf” is crucial. This capitalization signifies a shared language (often American Sign Language or other sign languages), a unique set of social norms, values, and a collective identity. It moves beyond a purely medical definition to encompass a rich cultural experience.Here are sentences demonstrating the cultural and identity-related usage of “Deaf”:

- Many members of the Deaf community find strength and belonging in shared cultural experiences and traditions.

- Her journey to embrace her Deaf identity was a transformative process, connecting her with a vibrant community.

- The Deaflympics showcases the athletic prowess and competitive spirit within the global Deaf population.

- Attending a Deaf event provided an invaluable opportunity to immerse myself in Deaf culture and learn about its history.

- He identifies as Deaf and is an active participant in local Deaf community organizations.

“deaf” (Lowercase d) in Audiological and Descriptive Contexts

The lowercase “d” in “deaf” is typically used to describe the audiological condition of not hearing or having significant hearing loss. This usage is often found in medical, scientific, or general descriptive contexts where the focus is on the physiological aspect rather than cultural identity.Here are sentences employing “deaf” to illustrate its audiological and descriptive function:

- The child was diagnosed as profoundly deaf at a young age.

- Research indicates that early intervention can significantly benefit individuals who are deaf.

- She has been deaf in her left ear since birth.

- The new hearing aid technology aims to improve the quality of life for people who are deaf.

- A significant percentage of the population experiences some degree of hearing loss, making them deaf to certain frequencies.

Hypothetical Dialogue Demonstrating Respectful Usage

This dialogue showcases how to navigate the use of both “Deaf” and “deaf” in a conversation, emphasizing respect for individual identity and audiological status. Scenario: Two colleagues, Sarah (who is hearing) and Mark (who identifies as Deaf), are discussing a new accessibility initiative at their workplace. Sarah: “Mark, I wanted to get your thoughts on the new captioning service we’re rolling out for all company videos.

We want to ensure it’s truly beneficial for everyone.” Mark: “That’s a great initiative, Sarah. For many of us in the Deaf community, effective captioning is essential for full participation. I’m glad the company is investing in this.” Sarah: “Absolutely. We’ve been working with a provider who specializes in accurate transcription. Are there any specific features you think would be most helpful for individuals who are deaf?” Mark: “Well, beyond just accuracy, having options for different caption styles and ensuring they are synchronized well with the audio is important.

Also, for those of us who use sign language as our primary communication, the availability of sign language interpretation alongside captions would be a fantastic addition.” Sarah: “That’s excellent feedback, Mark. We’ll definitely look into the sign language interpretation aspect. It’s crucial that we create an inclusive environment where everyone, whether they identify as Deaf or are deaf due to audiological reasons, feels supported.” Mark: “Thank you, Sarah.

I appreciate you taking the time to understand and implement these changes thoughtfully. It makes a real difference.”

Impact of Incorrect Capitalization in Communication

Using the wrong capitalization can inadvertently cause offense or misrepresent an individual’s identity. For instance, referring to someone who identifies as Deaf as “deaf” can be perceived as dismissive of their cultural identity and reduce their experience to a purely medical condition. Conversely, using “Deaf” when referring to a purely audiological condition without acknowledging any cultural connection might be seen as misapplied or even patronizing by those who do not identify with the Deaf community.Consider the impact of the following incorrect usage:

“The company hired a new employee who is deaf, and they immediately started implementing sign language in all meetings.”

This sentence, using “deaf” in lowercase, implies a purely audiological state. If the employee identifies as Deaf and is a member of the Deaf community, this sentence fails to acknowledge their cultural identity and the richness of their lived experience. A more respectful and accurate phrasing would be:

“The company hired a new employee who is Deaf, and they immediately started implementing sign language in all meetings.”

This revised sentence respects the individual’s cultural identity and acknowledges their connection to the Deaf community. The subtle change in capitalization significantly alters the perception of the statement, moving from a purely descriptive audiological note to an acknowledgment of cultural belonging.

Linguistic and Social Implications

The way we use language, particularly concerning labels for identities and conditions, is not static. It evolves alongside societal understanding, activism, and the lived experiences of the communities involved. The distinction between “Deaf” and “deaf” is a prime example of this linguistic and social evolution, reflecting a shift in how audiological differences are perceived and how cultural identities are claimed.Language is a powerful tool that shapes our perceptions and interactions.

The terms we choose to describe groups of people can either reinforce existing stereotypes and marginalization or actively challenge them, fostering greater understanding and inclusivity. The ongoing evolution of terminology within the Deaf community highlights the critical role of language in social movements and the assertion of identity.

Evolution of Terminology and Social Movements

The terminology used to describe individuals with hearing loss has undergone significant transformation, mirroring the progress of social movements advocating for the rights and recognition of the Deaf community. Early terminology often focused solely on the audiological deficit, framing hearing loss as a medical condition to be “cured” or “fixed.” However, as Deaf individuals began to organize and assert their cultural identity, the language used to describe them shifted.

The capitalization of “Deaf” emerged as a deliberate act of cultural reclamation, signifying a shared language, history, social norms, and a distinct way of life, separate from the purely medical or audiological perspective of “deafness.” This linguistic shift is inextricably linked to the broader Deaf rights movement, which fought for educational access, sign language recognition, and an end to discrimination.

Language Choices Reflect Societal Attitudes

The language employed to discuss audiological conditions and cultural identities offers a window into prevailing societal attitudes. When “deaf” is consistently used in a purely medical context, it can inadvertently reinforce the notion of a deficiency or disability. Conversely, the deliberate use of “Deaf” by members of the Deaf community signals a rejection of this deficit model and an embrace of a rich and vibrant culture.

This linguistic choice challenges the dominant audist perspective, which often prioritizes hearing as the norm and views hearing loss through a lens of impairment. The shift in language reflects a growing societal awareness and a move towards valuing diverse experiences and identities.

Role of Language in Reinforcing or Challenging Perceptions

Language plays a dual role in shaping perceptions: it can either perpetuate existing biases or actively dismantle them. The consistent use of “deaf” without acknowledging the cultural implications can reinforce the perception of hearing loss as solely a medical issue, potentially leading to assumptions about an individual’s capabilities and experiences. On the other hand, understanding and adopting the distinction between “Deaf” and “deaf” serves as a powerful tool to challenge these ingrained perceptions.

By recognizing “Deaf” as an identity and culture, we move beyond a narrow, audiological framework and acknowledge the multifaceted realities of individuals who are hard of hearing or profoundly deaf. This linguistic nuance is crucial in fostering a more accurate and respectful understanding.

Understanding Linguistic Nuances Contributes to Inclusivity

Appreciating the distinction between “Deaf” and “deaf” is fundamental to fostering genuine inclusivity. It moves beyond a superficial understanding of audiological status to a deeper recognition of cultural identity, community, and lived experience. This awareness allows for more respectful communication, more effective advocacy, and the creation of environments where individuals feel seen, valued, and understood. When we use the appropriate terminology, we signal our respect for a person’s self-identity and acknowledge the richness of the Deaf community and its contributions to society.

This linguistic sensitivity is a cornerstone of building a truly inclusive world.

Final Review

In essence, grasping the distinction between “Deaf” and “deaf” is crucial for fostering respectful and inclusive communication. It acknowledges that hearing status can be both a medical condition and a vital aspect of cultural identity, and by honoring individual preferences in terminology, we contribute to a more understanding and accepting society.