How to Use Classifiers to Describe Shapes and Sizes sets the stage for this enthralling narrative, offering readers a glimpse into a story that is rich in detail with formal and friendly language style and brimming with originality from the outset.

This exploration delves into the fascinating world of classifiers, powerful tools that enable machines to perceive and articulate the fundamental characteristics of objects. We will uncover how these algorithms dissect visual information, transforming raw data into meaningful descriptions of form and scale, essential for a myriad of applications.

Introduction to Classifiers for Geometric Description

Classifiers are powerful tools that enable us to systematically identify and categorize objects based on their inherent characteristics. When applied to geometric description, these classifiers act as intelligent agents, capable of discerning and labeling shapes and sizes with remarkable accuracy. This process is fundamental to how we understand and interact with the physical world, allowing us to differentiate between a circle and a square, or a small object from a large one.The ability to accurately describe shapes and sizes is not merely an academic exercise; it holds significant practical importance across a multitude of fields.

From engineering and manufacturing, where precise dimensions are critical for component fit and function, to medical imaging, where the shape and size of anomalies can indicate disease, and even in everyday applications like robotics and augmented reality, a clear geometric understanding is paramount. Classifiers provide an automated and scalable solution for extracting this vital information from visual data.At their core, classifiers for geometric description are designed to extract a variety of informative features about an object’s form.

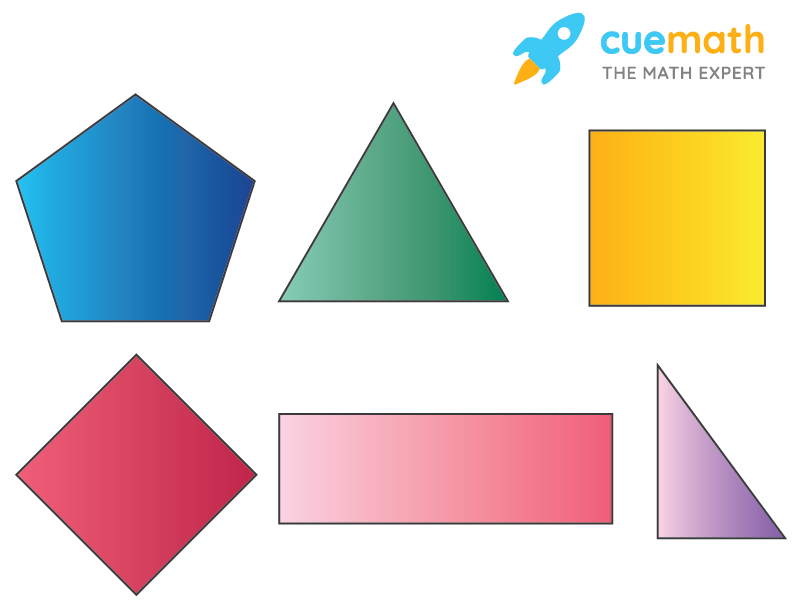

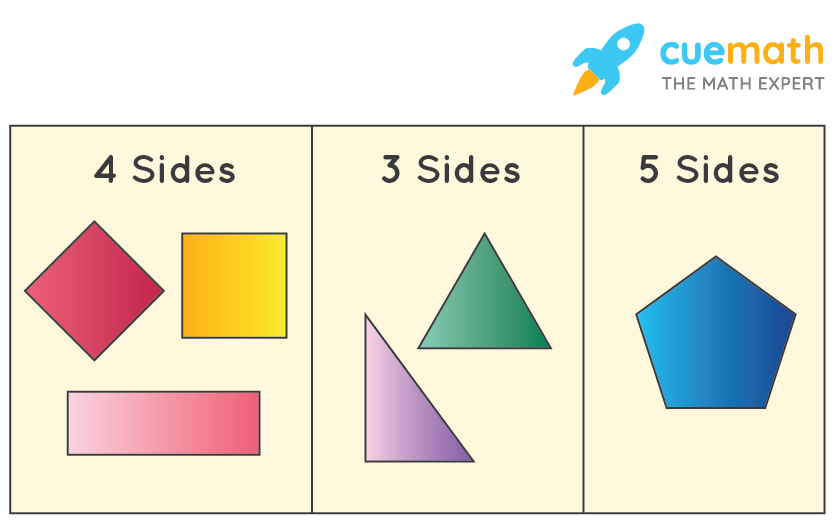

These features can include, but are not limited to, the number of sides, the presence of curves or straight lines, angles, symmetry, aspect ratio, and overall dimensionality. By analyzing these attributes, a classifier can assign an object to a predefined category, such as “triangle,” “rectangle,” “circle,” or even more complex shapes.To better understand how classifiers operate, consider an analogy: imagine a highly organized sorting system in a warehouse.

When a new item arrives, it is examined for specific characteristics – its shape, its weight, its material. Based on these characteristics, the item is then placed into a designated bin or shelf. Similarly, a geometric classifier examines an image or a set of data points representing an object, extracts its geometric features, and then “sorts” it into the appropriate shape and size category.

This systematic approach ensures that each object is correctly identified and can be processed or understood accordingly.

Types of Classifiers for Shape and Size

Understanding how to effectively describe shapes and sizes using machine learning relies heavily on the choice and implementation of appropriate classifiers. These algorithms are the engines that learn to distinguish between different geometric properties based on extracted features. The success of these classifiers is intrinsically linked to the quality and relevance of the features provided to them, as they lack inherent geometric intuition.The process begins with transforming raw data, such as image pixels or point cloud coordinates, into meaningful numerical representations called features.

These features capture essential characteristics of the shape and size, allowing the classifier to perform its learning and prediction tasks. Without robust feature extraction, even the most sophisticated classifier would struggle to differentiate between a square and a circle, or to accurately gauge the scale of an object.

Common Machine Learning Classifiers for Geometric Tasks

Several machine learning algorithms have proven effective in classifying shapes and sizes. Each offers distinct advantages depending on the complexity of the data and the desired outcome.

- Support Vector Machines (SVM): SVMs are powerful for classification tasks, particularly when dealing with high-dimensional data. They work by finding an optimal hyperplane that maximally separates different classes in the feature space. For geometric descriptions, SVMs can effectively distinguish between shapes by identifying the boundaries in feature representations.

- Decision Trees: These algorithms create a tree-like structure where internal nodes represent tests on features, branches represent the outcomes of these tests, and leaf nodes represent the class labels. Decision trees are intuitive and interpretable, making them useful for understanding which features are most discriminative for shape and size classification.

- Neural Networks: Especially Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), have revolutionized image-based shape and size recognition. CNNs can automatically learn hierarchical features from raw pixel data, eliminating the need for manual feature engineering in many cases. Deeper networks can capture complex spatial relationships, leading to highly accurate classifications.

Feature Extraction for Shape Understanding

The ability of a classifier to understand shape is directly dependent on the features extracted from the geometric data. These features act as a language that the classifier uses to interpret the input.

- Geometric Descriptors: Features such as area, perimeter, aspect ratio, eccentricity, and moments (e.g., Hu moments) are fundamental for describing shape. For instance, a circle will have a high aspect ratio close to 1 and a consistent perimeter-to-area ratio, while a long, thin rectangle will have a low aspect ratio.

- Topological Features: These describe the connectivity and structure of shapes, such as the number of holes or connected components. While less common for simple shape discrimination, they become important for more complex object recognition.

- Boundary and Contour Features: Analyzing the Artikel of a shape can reveal its characteristics. Features like curvature, corner detection, and shape signatures can effectively differentiate between irregular and regular shapes.

Classifier Strengths in Handling Size Variations

Classifiers can be adapted or inherently suited to handle variations in object size. The key is often in the choice of features and how they are normalized or scaled.

- Scale-Invariant Features: Some features, by their nature, are less affected by size changes. For example, ratios of lengths or areas (e.g., aspect ratio) remain constant regardless of the overall size of the object.

- Normalization Techniques: Before feeding data into a classifier, features can be normalized to a standard range (e.g., 0 to 1) or scaled based on a reference size. This ensures that size differences do not disproportionately influence the classification outcome.

- Hierarchical Feature Learning (Neural Networks): CNNs, in particular, can learn features at different scales. Early layers might detect edges, while deeper layers can combine these to recognize larger structures, making them robust to scale variations.

Features for Distinguishing Squares and Circles, and Small vs. Large Objects

Specific features are crucial for differentiating between distinct shapes and their sizes.

Distinguishing Squares and Circles

To differentiate between a square and a circle, classifiers would typically look for features that capture their inherent geometric properties:

- Aspect Ratio: A square has an aspect ratio of 1 (width/height). A circle also has an aspect ratio of 1. This feature alone is insufficient.

- Perimeter-to-Area Ratio: A circle has the minimum perimeter-to-area ratio for a given area. A square will have a higher ratio.

- Moments: Central moments, such as the second-order central moments, can capture the distribution of pixels. For a perfect circle, these moments are rotationally invariant. For a square, they would differ based on orientation unless rotational invariance is explicitly handled.

- Corner Detection: Squares have distinct corners, which can be identified using algorithms like Harris corner detection. Circles have no sharp corners.

Distinguishing Small vs. Large Objects

To classify objects as small or large, classifiers primarily rely on features that are directly related to scale:

- Absolute Size Features: Direct measurements like area, perimeter, bounding box dimensions (width, height), or volume (in 3D) are primary indicators. For example, a classifier might be trained to recognize objects with an area greater than a certain threshold as “large.”

- Normalized Features: If scale-invariant features are used for shape, then a separate set of features or a meta-classifier might be employed to determine absolute size. This could involve comparing the object’s size to known reference objects within the scene or dataset.

- Density of Features: In some contexts, the density of features within a given area can indirectly indicate size. For instance, if a fixed-size window is applied, a larger object will encompass more of these features.

For example, in an image processing task to identify furniture, a classifier might use the bounding box width and height. If both are above 100 pixels, it might be classified as a “large” item like a sofa. If they are below 20 pixels, it might be a “small” item like a coaster.

Feature Engineering for Shape and Size Classification

The effectiveness of any classifier heavily relies on the quality of the features it uses. For shape and size classification, this means extracting and engineering numerical representations that capture the geometric essence of an object. This process involves understanding which geometric properties are most discriminative and how to represent them in a way that is both informative and manageable for machine learning algorithms.Feature engineering is the art and science of transforming raw data into features that better represent the underlying problem to the predictive models, resulting in improved accuracy.

In the context of shape and size, it involves selecting, transforming, and creating features that highlight differences and similarities between geometric forms. This step is crucial because raw pixel data or simple boundary points often do not directly convey shape information in a format suitable for classification.

Selecting and Engineering Relevant Shape Features

The selection of features is paramount to building a robust shape classifier. The goal is to identify characteristics that are invariant to translation, rotation, and scaling where appropriate, or that explicitly capture these transformations if they are part of the classification task. For 2D shapes, a rich set of features can be derived from their boundaries and filled areas.The process begins with an initial representation of the shape, such as a binary mask or a set of contour points.

From this representation, various geometric descriptors can be calculated. These descriptors aim to quantify aspects like elongation, roundness, complexity, and spatial distribution of pixels.

Perimeter, Area, Aspect Ratio, and Moments

Several fundamental geometric properties provide a strong basis for shape description. These features are often calculated from the shape’s contour or its binary mask.

- Perimeter: This is the total length of the boundary of the shape. It provides a measure of the “extent” of the shape’s edge. For example, a circle and a square with the same area might have different perimeters.

- Area: This represents the total number of pixels enclosed by the shape’s boundary. It is a fundamental measure of the shape’s “size.”

- Aspect Ratio: This is the ratio of the shape’s longest dimension to its shortest dimension. It is a simple yet effective measure of elongation. For instance, a rectangle with sides 2×10 would have an aspect ratio of 5, while a square with sides 5×5 would have an aspect ratio of 1.

- Moments: Image moments are quantitative measures of the shape’s image. They can capture information about the shape’s distribution of pixel intensities (or presence in a binary mask). Central moments, in particular, are translation-invariant. Hu moments are a set of seven moments that are invariant to translation, scale, and rotation, making them very powerful for shape recognition. The calculation of the second-order central moments, for example, can provide information about the shape’s orientation and spread along different axes.

A common formula for calculating the area (A) of a binary image using pixel summation is:

A = ∑i=1N 1

where N is the number of foreground pixels.The aspect ratio (AR) can be calculated from the principal axes of the shape:

AR = λmax / λ min

where λ max and λ min are the eigenvalues of the covariance matrix of the shape’s pixel coordinates, representing the variances along the principal axes.

Methods for Normalizing Features

When classifying shapes, it is essential to account for variations in size. A classifier trained on small triangles and large triangles should ideally recognize both as triangles. Normalization techniques ensure that features are comparable across different scales.Several methods can be employed for feature normalization:

- Scaling to a Unit Size: Features like area and perimeter can be normalized by dividing them by a characteristic length scale of the object, such as the square root of the area for area-based normalization or the perimeter itself for perimeter-based normalization.

- Min-Max Scaling: This method rescales features to a fixed range, typically [0, 1] or [-1, 1]. For a feature ‘x’, the formula is:

xnormalized = (x – x min) / (x max

-x min)This is useful when the absolute values of features are less important than their relative distribution.

- Z-score Normalization (Standardization): This method centers the feature by subtracting the mean and then scales it by the standard deviation. The formula is:

xstandardized = (x – μ) / σ

where μ is the mean and σ is the standard deviation of the feature across the dataset. This method is useful when features have different scales and distributions.

- Using Scale-Invariant Features: As mentioned earlier, features like Hu moments are inherently invariant to scale, translation, and rotation, thus requiring no explicit normalization for these transformations.

Feature Set for Distinguishing Basic 2D Shapes

To distinguish between basic 2D shapes like triangles, rectangles, and ellipses, a simple yet effective feature set can be designed. This set should capture key characteristics that differentiate these forms.Consider the following features for a given shape represented by a binary mask:

- Area: A fundamental measure of size.

- Perimeter: The length of the boundary.

- Compactness: A measure of how “round” a shape is. It is often defined as (4

- PI

- Area) / (Perimeter^2). A perfect circle has a compactness of 1, while other shapes have values less than 1.

- Aspect Ratio: As described before, the ratio of the longest to shortest dimension.

- Circularity: Another measure of roundness, often defined as (4

- Area) / (PI

- Diameter^2), where Diameter is the diameter of the smallest circle enclosing the shape.

Let’s illustrate how these features might differentiate the shapes:

| Shape | Typical Area | Typical Perimeter | Typical Compactness (4πA/P²) | Typical Aspect Ratio | Typical Circularity (4A/πD²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triangle (equilateral) | Varies | Varies | ~0.605 | 1.0 | ~0.605 |

| Rectangle (square) | Varies | Varies | ~0.785 | 1.0 | ~0.785 |

| Rectangle (elongated) | Varies | Varies | < 0.785 | > 1.0 | < 0.785 |

| Ellipse (circle) | Varies | Varies | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Ellipse (elongated) | Varies | Varies | < 1.0 | > 1.0 | < 1.0 |

Note that for triangles and rectangles, the exact values of compactness and circularity depend on their specific proportions. For instance, an equilateral triangle will have different compactness than an isosceles or scalene triangle. Similarly, a square will have higher compactness than a very thin rectangle. Ellipses, particularly circles, tend to have higher compactness and circularity values. The aspect ratio is particularly useful for distinguishing between elongated shapes (rectangles, ellipses) and more regular ones (squares, circles, equilateral triangles).

Implementing Classifiers for Shape and Size Detection

Having successfully extracted relevant features, the next crucial step is to train a classifier that can learn to distinguish between different shapes and sizes based on these features. This process involves a systematic approach to prepare your data, train the model, and then evaluate its effectiveness. This section will guide you through the practical implementation of classifiers for shape and size detection.The general workflow for training a classifier to recognize shapes and sizes involves several key stages.

It begins with data preparation, where you gather and label a dataset that represents the variety of shapes and sizes you aim to detect. Following this, feature extraction is performed on this dataset. Once features are extracted, they are fed into a chosen classifier model for training. The model learns the patterns and relationships between the extracted features and their corresponding labels.

Finally, the trained model’s performance is rigorously evaluated to ensure its accuracy and reliability.

Dataset Preparation for Shape and Size Classification

A well-prepared dataset is fundamental for training an effective classifier. This involves curating a collection of images that accurately represent the shapes and sizes you wish to classify, and then meticulously labeling each image with the correct shape and size information. This meticulous labeling ensures that the classifier learns from accurate ground truth.A step-by-step procedure for preparing a dataset of images with labeled shapes and sizes is as follows:

- Image Acquisition: Gather a diverse set of images that contain the shapes and sizes of interest. This could involve taking photographs, using synthetic data generation, or sourcing images from existing datasets. Ensure the images capture variations in lighting, background, and orientation to promote robustness.

- Shape and Size Annotation: For each image, carefully annotate the specific shapes and their corresponding sizes. This can be done manually by drawing bounding boxes or segmentation masks around the objects and assigning predefined labels (e.g., ‘circle’, ‘square’, ‘large’, ‘small’). Tools like Labelbox, VGG Image Annotator (VIA), or Computer Vision Annotation Tool (CVAT) can be instrumental in this process.

- Data Splitting: Divide the annotated dataset into three subsets: a training set, a validation set, and a test set. A common split ratio is 70% for training, 15% for validation, and 15% for testing. The training set is used to train the model, the validation set helps in tuning hyperparameters and preventing overfitting during training, and the test set provides an unbiased evaluation of the final model’s performance.

- Data Augmentation (Optional but Recommended): To increase the size and diversity of the training data without collecting new images, apply data augmentation techniques. This includes operations like random rotations, flips, scaling, cropping, and color jittering. For example, rotating an image of a square by 45 degrees still represents a square, thus expanding the training examples.

Feeding Extracted Features into a Classifier Model

Once features have been extracted from the prepared dataset, the next critical step is to feed these features into a chosen machine learning classifier. This process allows the model to learn the decision boundaries that separate different shape and size categories. The format and structure of the features will dictate how they are presented to the classifier.The process of feeding extracted features into a chosen classifier model can be understood through these points:

- Feature Vector Creation: Each image, after feature extraction, will result in a feature vector. For instance, if you extract shape descriptors like Hu moments and size descriptors like area and aspect ratio, a single image might be represented by a vector like [Hu1, Hu2, …, Hu7, Area, AspectRatio].

- Classifier Selection: Choose an appropriate classifier based on the nature of your features and the complexity of the classification task. Common choices include Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Logistic Regression, Random Forests, and K-Nearest Neighbors (KNN). For more complex tasks, deep learning models like Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can be used, where feature extraction and classification are often integrated.

- Model Training: The feature vectors and their corresponding labels are fed into the selected classifier. The classifier’s algorithm then adjusts its internal parameters to minimize prediction errors on the training data. For example, an SVM would find an optimal hyperplane to separate the feature vectors of different shapes.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: The validation set is used to tune the hyperparameters of the chosen classifier. Hyperparameters are settings that are not learned from the data but are set before training begins, such as the kernel type and regularization parameter in an SVM, or the number of trees in a Random Forest. This step is crucial for optimizing the model’s generalization ability.

Evaluating Classifier Performance

Assessing the performance of a trained shape and size classifier is essential to understand its accuracy and identify areas for improvement. This involves using a separate test dataset, unseen during training and validation, to obtain an objective measure of how well the classifier generalizes to new data. Various metrics are employed to quantify different aspects of performance.A basic framework for evaluating the performance of a shape and size classifier includes:

- Prediction on Test Set: Use the trained classifier to predict the shapes and sizes for all the images in the test set. This generates a set of predicted labels for each image.

- Confusion Matrix: A confusion matrix is a table that summarizes the classification results. It shows the number of true positives, true negatives, false positives, and false negatives for each class. For example, it can reveal how often a ‘circle’ is misclassified as an ‘ellipse’.

- Accuracy: This is the most straightforward metric, calculated as the total number of correct predictions divided by the total number of predictions. It gives an overall sense of how often the classifier is right.

- Precision and Recall:

- Precision measures the accuracy of positive predictions. For a given class, it is the proportion of correctly identified positive instances out of all instances predicted as positive. High precision means fewer false positives.

- Recall (also known as sensitivity) measures the classifier’s ability to find all the positive instances. For a given class, it is the proportion of correctly identified positive instances out of all actual positive instances. High recall means fewer false negatives.

- F1-Score: The F1-score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a single metric that balances both. It is particularly useful when dealing with imbalanced datasets where one class might be much more frequent than others.

- ROC Curve and AUC: For binary classification or one-vs-rest scenarios, the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve plots the true positive rate against the false positive rate at various threshold settings. The Area Under the Curve (AUC) provides a single measure of the classifier’s ability to distinguish between classes. A higher AUC indicates better performance.

By analyzing these metrics, one can gain a comprehensive understanding of the classifier’s strengths and weaknesses, guiding further refinement or deployment decisions.

Real-World Applications of Shape and Size Classifiers

The ability to accurately classify shapes and sizes is a cornerstone technology enabling sophisticated automation and intelligent systems across a wide array of industries. From the intricate movements of robots on an assembly line to the subtle distinctions in medical scans, these classifiers provide the fundamental understanding of the physical world that machines need to operate effectively and to interpret complex data.

This section explores some of the most impactful applications where shape and size classification plays a critical role.The practical implementation of shape and size classifiers has revolutionized how we approach tasks that were once exclusively human domains. By enabling machines to perceive and categorize objects based on their geometric properties, we unlock new levels of efficiency, precision, and insight.

Robotics and Automation

In robotics and automation, shape and size classifiers are indispensable for enabling robots to interact intelligently with their environment. These systems allow robots to identify, locate, and manipulate objects, forming the basis for automated manufacturing, logistics, and even exploration.The following are key applications within robotics and automation:

- Object Recognition and Grasping: Robots can identify specific parts or products on an assembly line by their distinct shapes and sizes, allowing for precise grasping and placement. For example, a robotic arm in an electronics factory can differentiate between various sizes of screws or integrated circuits for automated assembly.

- Navigation and Obstacle Avoidance: Autonomous mobile robots, such as those used in warehouses or for delivery, rely on shape and size classification to identify and navigate around obstacles. They can distinguish between static objects like walls and dynamic ones like people or other vehicles, adjusting their path accordingly.

- Assembly and Sorting: In automated assembly lines, robots use shape and size classifiers to sort components before assembly or to ensure that parts are oriented correctly. This is crucial for tasks requiring high precision, like fitting gears or assembling intricate machinery.

- Inspection and Verification: Robots equipped with vision systems can inspect manufactured goods for defects by comparing the shape and size of the product against a known standard. Deviations can indicate manufacturing errors, allowing for immediate rejection or rework.

Medical Imaging for Anomaly Identification

The field of medical imaging heavily relies on shape and size classifiers to aid in the diagnosis and monitoring of diseases. By analyzing the geometric characteristics of anatomical structures or pathological formations, medical professionals can gain crucial insights into a patient’s health status.The following are critical applications in medical imaging:

- Tumor Detection and Characterization: Classifiers can identify and characterize potential tumors by their shape, size, and texture in imaging modalities like CT scans, MRIs, and X-rays. For instance, the irregular shape and rapid growth in size of a lesion might indicate malignancy, prompting further investigation.

- Organ Segmentation and Measurement: These classifiers are used to accurately segment organs from surrounding tissues, enabling precise measurement of their size and volume. Changes in organ size can be indicative of various conditions, such as organ enlargement in heart failure or shrinkage in degenerative diseases.

- Blood Vessel Analysis: Identifying and measuring the diameter and shape of blood vessels is vital for diagnosing conditions like aneurysms (abnormal bulges) or stenoses (narrowing). Classifiers help in detecting these anomalies and monitoring their progression.

- Cellular Morphology Analysis: In pathology, classifiers can analyze the shape and size of cells under a microscope to identify abnormal cell types, which is fundamental for diagnosing cancers and other cellular disorders.

Quality Control and Manufacturing Inspection

In manufacturing, ensuring product quality is paramount, and shape and size classifiers are at the forefront of automated inspection processes. They provide a consistent and objective method for verifying that products meet specified dimensions and tolerances.The following are key uses in quality control and manufacturing inspection:

- Dimensional Verification: Automated inspection systems use classifiers to measure critical dimensions of manufactured parts, such as length, width, diameter, and angles, ensuring they fall within acceptable manufacturing tolerances. This is vital for parts used in automotive, aerospace, and electronics industries.

- Defect Detection: Classifiers can identify surface defects like scratches, dents, or misalignments by recognizing deviations from the expected shape or size. For example, a bottle cap’s thread pattern must match a specific shape and size to seal correctly.

- Assembly Verification: In complex assemblies, classifiers can confirm that all components are present and correctly positioned by checking their shapes and relative sizes. This prevents the shipment of faulty products.

- Material Sorting: In bulk manufacturing, shape and size classifiers can sort raw materials or finished components based on their geometric properties, ensuring that only appropriate items proceed to the next stage of production.

Augmented Reality Experiences

Augmented reality (AR) overlays digital information onto the real world, and accurate shape and size description is crucial for creating immersive and interactive AR experiences. The ability to understand the geometry of objects allows AR systems to place virtual content realistically and enable meaningful interactions.The following scenarios highlight the importance of shape and size description in AR:

- Virtual Object Placement: AR applications need to understand the shape and size of real-world surfaces and objects to place virtual furniture in a room, virtual decorations on a wall, or virtual characters that interact realistically with the environment. A virtual sofa must fit within the available space and align with the floor’s dimensions.

- Interactive Product Visualization: Consumers can use AR to visualize products in their own space before purchasing. Classifiers help AR systems render virtual products at their correct scale and shape, allowing users to assess fit and appearance accurately.

- Gaming and Entertainment: AR games often require understanding the geometry of the user’s surroundings to create engaging gameplay. This includes recognizing flat surfaces for placing game elements or identifying the size of objects that can be interacted with in the virtual world.

- Spatial Mapping and Measurement: AR applications can use shape and size classifiers to create 3D maps of environments or to provide accurate measurements of real-world objects, useful for interior design, construction, or even simple DIY tasks.

Challenges and Advanced Techniques

While traditional methods for shape and size classification have proven useful, real-world scenarios often present complexities that require more sophisticated approaches. This section delves into common hurdles encountered in this domain and explores advanced techniques, particularly those leveraging deep learning, to overcome them and achieve robust classification.The ability to accurately describe and classify shapes and sizes is fundamental to many computer vision tasks.

However, the variability inherent in visual data can pose significant challenges. Understanding these challenges and the advanced techniques designed to address them is crucial for developing effective and reliable shape and size classification systems.

Common Challenges in Shape and Size Classification

Classifying shapes and sizes in images is not always straightforward due to various environmental and object-related factors. These challenges can significantly impact the performance and accuracy of classification models.

- Occlusion: When parts of an object are hidden by other objects or elements in the scene, it becomes difficult for the classifier to discern its complete shape and size. Partial visibility can lead to misclassification or an inability to classify altogether.

- Illumination Changes: Variations in lighting conditions, such as shadows, glare, or low light, can alter the appearance of an object, affecting its perceived shape and texture. This can confuse classifiers trained on images with different lighting.

- Scale Variation: Objects can appear at vastly different scales within an image, depending on their distance from the camera. A classifier needs to be able to recognize the same shape or size regardless of whether it occupies a large or small portion of the image.

- Background Clutter: Complex or noisy backgrounds can make it difficult to isolate the object of interest, leading to misinterpretations of its boundaries and features.

- Deformation and Articulation: Some objects, like animals or flexible materials, can change their shape or posture. Classifiers must be robust to these natural deformations.

- Viewpoint and Perspective Changes: The appearance of an object changes depending on the angle from which it is viewed. A shape that looks like a circle from one angle might appear as an ellipse from another.

Deep Learning for Automatic Feature Learning

Deep learning, especially Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), has revolutionized shape and size classification by automating the process of feature extraction. Unlike traditional methods that rely on hand-crafted features, CNNs learn hierarchical representations of the input data directly from the images.CNNs are structured in layers, with early layers detecting simple features like edges and corners, and deeper layers combining these to recognize more complex patterns and ultimately, entire shapes.

This automatic learning capability makes them highly effective for capturing the intricate details necessary for accurate shape and size description.

“Deep learning models, particularly CNNs, excel at learning discriminative features directly from raw pixel data, making them highly adaptable to the complexities of shape and size variations.”

Handling Multi-Scale Object Detection and Classification

Objects of interest often appear at different scales within an image, posing a challenge for classifiers that might be trained on a specific scale. Advanced techniques are employed to ensure that classifiers can effectively detect and classify objects regardless of their size.

- Feature Pyramid Networks (FPNs): FPNs build a pyramid of feature maps at different resolutions from a single input image. This allows the network to detect objects at various scales by processing features from different levels of the pyramid.

- Scale-Aware Training: Training models with data that includes objects at a wide range of scales helps the network generalize better. This can involve data augmentation techniques that resize objects.

- Region Proposal Networks (RPNs): In object detection frameworks like Faster R-CNN, RPNs are used to propose potential object regions at multiple scales, which are then passed to a classifier.

Improving Robustness to Orientation and Perspective Variations

Ensuring that a classifier can identify a shape or size correctly, irrespective of its orientation or the viewing perspective, is critical for real-world applications. Several techniques are used to enhance this robustness.

- Data Augmentation: Applying transformations like rotation, flipping, and perspective warping to training data artificially increases the diversity of viewpoints and orientations the model sees. This helps it learn to invariant features.

- Invariant Feature Descriptors: While CNNs learn features automatically, research continues into developing or enhancing features that are inherently less sensitive to rotation and scale.

- 3D-Aware Architectures: For more challenging scenarios, models that incorporate 3D information or explicitly reason about pose can be developed. These might involve techniques like pose estimation or learning from 3D models.

- Canonical View Synthesis: Some methods aim to transform an object’s appearance to a “canonical” or standard view before classification, simplifying the task for the classifier.

Illustrative Examples of Classifier Output

Understanding how classifiers present their findings is crucial for interpreting their effectiveness and applying them in practical scenarios. This section delves into concrete examples of classifier outputs, illustrating the descriptive power and decision-making process of these algorithms when identifying shapes and sizes.When a classifier identifies an object, its output is typically a set of labels or attributes that describe the object’s characteristics.

These descriptions can range from simple categorical labels to more detailed probabilistic assignments. The goal is to translate complex visual data into understandable and actionable information.

Describing a “Large Blue Sphere”

Imagine a scenario where a vision system is tasked with identifying objects on a conveyor belt. A classifier, after processing an image, might produce an output for a specific object that reads as follows:

- Shape: Sphere (Confidence: 0.98)

- Color: Blue (Confidence: 0.95)

- Size: Large (Confidence: 0.92)

This output clearly indicates that the classifier is highly confident that the object is a sphere, is blue in color, and is considered large. The confidence scores provide a measure of certainty for each attribute, allowing users to gauge the reliability of the classification.

Differentiating Between Rectangles of Varying Proportions

Classifiers are adept at distinguishing subtle variations in shape. Consider the task of differentiating between a “thin, elongated rectangle” and a “short, wide rectangle.” A classifier would analyze features such as the aspect ratio (the ratio of length to width) and the absolute dimensions.For a thin, elongated rectangle, the classifier might report:

- Shape: Rectangle (Confidence: 0.99)

- Aspect Ratio: 5.0 (indicating length is 5 times the width)

- Size Category: Long and Narrow (Confidence: 0.90)

Conversely, for a short, wide rectangle, the output could be:

- Shape: Rectangle (Confidence: 0.99)

- Aspect Ratio: 0.2 (indicating width is 5 times the length)

- Size Category: Short and Wide (Confidence: 0.91)

The classifier uses precise measurements and derived features like the aspect ratio to make these fine-grained distinctions, going beyond a simple “rectangle” label.

Classifier Output for Diverse Geometric Objects

Let’s consider a set of diverse geometric objects presented to a classifier. The output for a collection of items might be presented in a tabular format for clarity:

| Object ID | Detected Shape | Confidence (Shape) | Detected Size | Confidence (Size) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Circle | 0.97 | Medium | 0.94 |

| 2 | Square | 0.99 | Small | 0.96 |

| 3 | Triangle (Equilateral) | 0.93 | Large | 0.91 |

| 4 | Rectangle (Elongated) | 0.98 | Medium | 0.93 |

| 5 | Oval | 0.90 | Small | 0.89 |

This table provides a comprehensive overview of the classifier’s analysis for each object, detailing both its identified shape and its relative size, along with the associated confidence levels.

Textual Representation of Classifier Analysis with Confidence

A more detailed textual analysis for a single object might look like this:

The object has been analyzed, and the primary shape classification is “Cylinder.” The classifier assigns a high confidence score of 0.96 to this shape determination. Regarding its size, the object is categorized as “Medium-Sized.” This size classification carries a confidence level of 0.

91. Further analysis indicates that the aspect ratio of the cylinder is approximately 3

1, suggesting it is taller than it is wide.

This output provides not only the basic shape and size but also a measure of the classifier’s certainty and additional descriptive metrics like the aspect ratio, offering a richer understanding of the classified object.

Final Summary

In essence, mastering the art of shape and size classification unlocks a deeper understanding of the visual world, empowering machines to not only see but also to comprehend. From intricate medical analyses to seamless augmented reality experiences, the principles discussed here form the bedrock of intelligent perception, paving the way for even more sophisticated interactions with our environment.