Beginning with How to Use Indexing to Refer to People and Places, the narrative unfolds in a compelling and distinctive manner, drawing readers into a story that promises to be both engaging and uniquely memorable.

This guide delves into the fundamental concepts and practical applications of indexing, a powerful technique for organizing and retrieving information. We will explore how to effectively reference individuals and geographical locations within datasets, ensuring clarity and precision in information retrieval. Understanding these methods is crucial for anyone working with large volumes of data, from researchers and historians to developers and content creators.

Understanding Indexing for People and Places

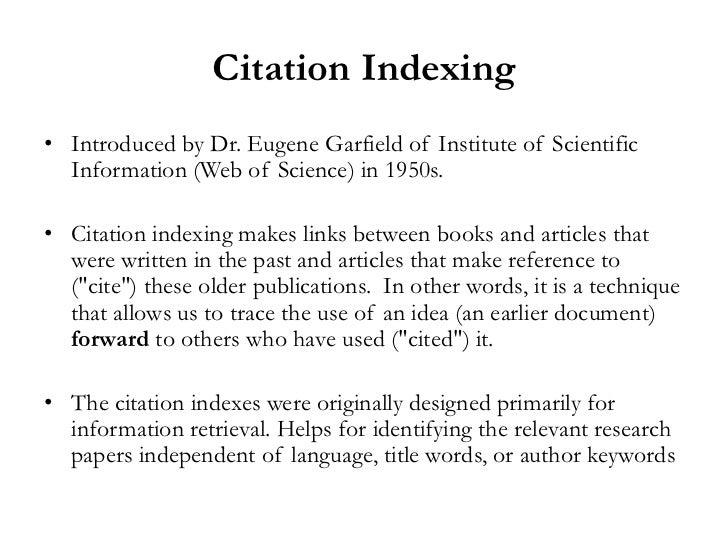

Indexing, in the realm of information retrieval, is the process of creating a structured catalog of data elements to enable swift and efficient access to specific information. It acts much like the index at the back of a book, allowing you to pinpoint precisely where a particular topic is discussed without having to read through the entire volume. This concept is fundamental to how we navigate vast digital landscapes, from search engines to library databases.Applying this principle to people and places allows us to organize and retrieve information related to individuals and geographical entities with remarkable precision.

It involves assigning unique identifiers or s that represent these entities, making them searchable and retrievable. This is crucial for tasks ranging from historical research and genealogical studies to managing large datasets of customer information or tracking global events.

Identifying and Referencing Specific Individuals

Indexing for people involves creating entries that uniquely identify individuals within a dataset or a larger information system. This goes beyond simply listing a name; it often involves associated metadata that helps to distinguish between individuals with the same name and provides context. The goal is to ensure that when you search for a person, you retrieve accurate and relevant information about that specific individual.Key elements that are often indexed for individuals include:

- Full Name: The complete name of the person.

- Aliases or Pseudonyms: Any other names the person is known by.

- Dates: Birth, death, or significant life event dates.

- Affiliations: Associations with organizations, groups, or families.

- Roles: Positions held, such as occupation, title, or relationship.

- Unique Identifiers: Such as social security numbers, employee IDs, or passport numbers (used with strict privacy controls).

For instance, in a historical archive, indexing might link a person’s name to their birth records, census data, military service files, and newspaper articles mentioning them. This allows a researcher to quickly gather a comprehensive profile of an individual’s life and contributions.

Locating Information About Geographical Locations

Indexing for places operates on similar principles, focusing on the unique characteristics of geographical entities. This allows for the efficient retrieval of data associated with specific cities, countries, landmarks, or regions. Effective indexing of places is vital for applications in geography, urban planning, travel, and logistics.Examples of how indexing helps locate information about geographical locations include:

- Geographic Coordinates: Latitude and longitude for precise mapping.

- Administrative Divisions: Country, state/province, county, city, and neighborhood.

- Topographical Features: Mountains, rivers, lakes, and coastlines.

- Man-made Structures: Cities, towns, roads, bridges, and significant buildings.

- Historical Names: Former names of places that may be used in older documents.

Consider a real estate database. Indexing each property by its address, zip code, city, and even neighborhood allows a user to search for properties within a specific radius, in a particular school district, or with certain nearby amenities. Similarly, a mapping service indexes roads and points of interest to provide navigation and local business information.

The Importance of Context When Using Indexing for People and Places

While indexing provides the mechanism for retrieval, the accuracy and usefulness of the information obtained heavily rely on the context in which it is used. Without proper context, an index entry can be ambiguous or lead to incorrect conclusions. Understanding the context ensures that the indexed information is interpreted correctly and applied appropriately.Context is crucial in several ways:

- Disambiguation: For people with common names, contextual information like middle names, birth dates, or associated locations helps distinguish between them. For places, context might involve differentiating between a city and a state with the same name, or identifying a historical landmark versus a modern one.

- Relevance: The purpose of the search dictates the necessary context. For historical research, the context might be a specific time period. For demographic analysis, the context could be population density or economic indicators.

- Granularity: The level of detail in the index needs to match the required context. Searching for a global event might require country-level indexing, while planning a local event requires street-level precision.

- Data Integrity: Ensuring that the indexed data is accurate and up-to-date is paramount. Outdated or incorrect contextual information can render even the most efficient index useless or misleading.

For example, an index entry for “Washington” could refer to the state, the District of Columbia, or a specific city. The context of the search query, such as “Washington D.C. museums” or “Washington state wineries,” is essential for the indexing system to return the correct results. Similarly, when indexing a person, their profession or the historical period they lived in provides critical context for understanding their life and achievements.

Practical Methods for Indexing People

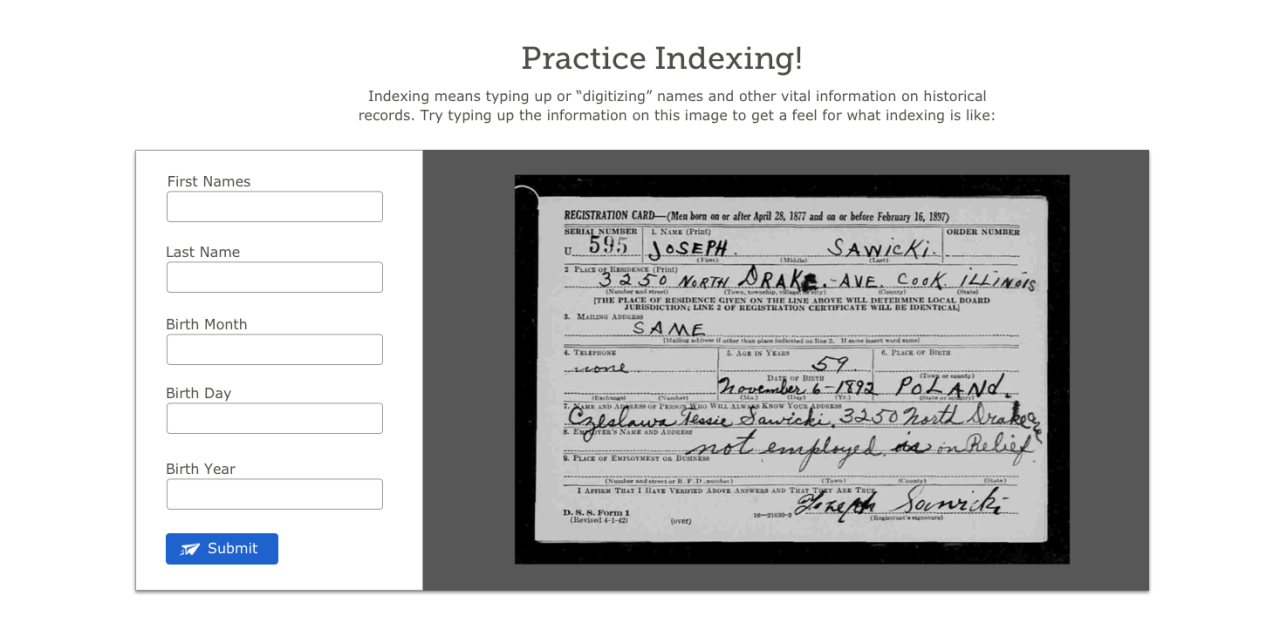

Indexing individuals within a dataset is a crucial step for efficient data retrieval and analysis. This section Artikels practical methods to create and manage indexes for people, ensuring accuracy and facilitating quick access to information about specific individuals.Effective indexing of people involves a systematic approach to data entry and management. By following established procedures, you can create robust indexes that support a wide range of analytical tasks, from simple lookups to complex relationship mapping.

Creating an Index of Individuals

To create an index of individuals, a structured, step-by-step procedure is essential. This process ensures that each person is uniquely identified and that their associated data is consistently organized.

- Data Collection and Standardization: Gather all relevant information about individuals. This typically includes full names, dates of birth, locations, occupations, and any other identifying details. Standardize the format of this data to ensure uniformity. For example, consistently use “Last Name, First Name Middle Initial” or a similar format.

- Unique Identifier Assignment: Assign a unique identifier to each individual. This can be a sequential number, a randomly generated ID, or a combination of key data points (e.g., birth year and first few letters of the last name). This identifier will be the primary key in your index.

- Index Structure Design: Decide on the structure of your index. A common approach is to use a relational database table where each row represents an individual and columns represent their attributes. Alternatively, for simpler datasets, a sorted list or a dictionary (key-value pairs) can suffice.

- Indexing Fields: Determine which fields will be indexed for quick searching. Typically, the unique identifier is always indexed. Other commonly indexed fields include full name, date of birth, and primary location.

- Populating the Index: Enter the standardized data into the chosen index structure. Ensure that each record is linked to its unique identifier.

- Verification and Validation: Regularly verify the accuracy and completeness of the index. Cross-reference with original data sources to catch any errors or omissions.

Disambiguating Individuals with Similar Names

A common challenge in indexing people is dealing with individuals who share the same or very similar names. Effective disambiguation techniques are vital to ensure that searches return accurate results and do not conflate different individuals.To overcome the complexities of similar names, a multi-faceted approach is recommended. This involves leveraging additional identifying information and employing systematic methods to differentiate between individuals.

- Using Differentiating Attributes: When names are identical or very similar, rely on other unique attributes. This can include:

- Dates of Birth: Even a difference of a few years can distinguish between individuals.

- Locations: A different city, state, or country of residence or origin is a strong differentiator.

- Occupations or Roles: Different professions or positions held can help.

- Parental or Sibling Information: Knowing family connections can resolve ambiguities.

- Specific Event Participation: Involvement in distinct historical events or projects.

- Employing a Canonical Name: For individuals with multiple known names or variations, establish a “canonical” or preferred name for indexing purposes. This could be their most commonly used name or their official name.

- Adding Suffixes or Prefixes: If necessary, append suffixes (e.g., “Jr.”, “Sr.”, “III”) or prefixes to names to create unique entries, especially in informal datasets.

- Utilizing a Fuzzy Matching Algorithm: For large datasets, consider using fuzzy matching algorithms. These algorithms can identify names that are “close” to each other, allowing for manual review and disambiguation of potential matches.

- Contextual Analysis: When searching, consider the context in which a name appears. If a document mentions “John Smith, the inventor,” and another mentions “John Smith, the politician,” the context provides the necessary disambiguation. The index can store these contextual clues.

Designing a Simple Indexing System for Historical Figures and Associations

Creating an index for historical figures and their associations requires a system that captures relationships and events. This system can be designed using a simple relational model or a graph-based approach.A well-designed indexing system for historical figures should go beyond just listing names. It needs to capture the intricate web of connections that define historical narratives.Consider a system with the following core components:

- Entity Table (People):

person_id(Primary Key, unique identifier)full_namebirth_datedeath_dateprimary_locationbrief_biography

- Association Table (Relationships):

association_id(Primary Key)person_id_1(Foreign Key to People table)person_id_2(Foreign Key to People table)relationship_type(e.g., “spouse”, “parent”, “child”, “colleague”, “rival”)start_dateend_date

- Event Table:

event_id(Primary Key)event_nameevent_datelocation

- Event Participation Table (Linking People to Events):

participation_id(Primary Key)person_id(Foreign Key to People table)event_id(Foreign Key to Event table)role_in_event(e.g., “leader”, “participant”, “witness”)

Example: To track the association between Marie Curie and Pierre Curie:

- In the

Peopletable, create entries for “Marie Curie” and “Pierre Curie” with their respective IDs. - In the

Associationtable, create an entry:person_id_1= ID for Marie Curieperson_id_2= ID for Pierre Curierelationship_type= “spouse”start_date= their marriage date

This structure allows for querying all spouses, all colleagues of a specific person, or all participants in a particular historical event.

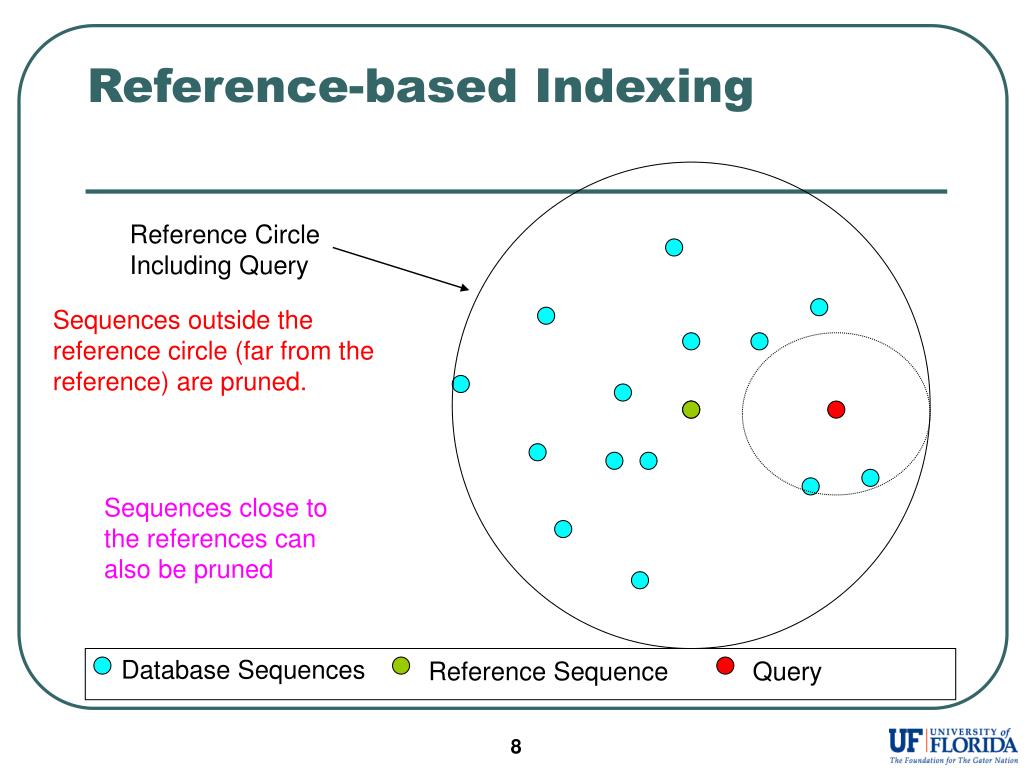

Using Indexing to Find All Mentions of a Particular Person

Indexing significantly enhances the ability to locate every instance where a specific person is mentioned across a collection of documents. This is achieved by creating an inverted index or by leveraging full-text search capabilities of databases.The power of indexing is most evident when performing comprehensive searches. By pre-processing documents and creating an index, retrieval becomes nearly instantaneous, even for vast amounts of text.Here’s how indexing facilitates finding all mentions:

- Document Pre-processing: Each document in the dataset is analyzed.

- Tokenization: Documents are broken down into individual words or terms (tokens). Punctuation and common “stop words” (like “the”, “a”, “is”) are often removed.

- Inverted Index Creation: An inverted index is a data structure that maps terms to the documents in which they appear. For each unique term, the index stores a list of document IDs and the positions within those documents where the term is found.

Example:Suppose you have three documents:* Document 1: “Albert Einstein developed the theory of relativity.”

Document 2

“The work of Albert Einstein revolutionized physics.”

Document 3

“Relativity is a cornerstone of modern physics.”An inverted index for the term “Albert Einstein” would look something like this:* “Albert Einstein”:

Document 1

Position 1

Document 2

Position 1When you search for “Albert Einstein”:

- The search system queries the inverted index for the term “Albert Einstein”.

- It retrieves the list of documents (Document 1, Document 2) and their positions where the name appears.

- The system then presents these documents as the search results.

For more sophisticated searches, such as finding mentions within a specific proximity of another term (e.g., “Albert Einstein” near “relativity”), the positional information in the inverted index is crucial. This allows for phrase searching and proximity searching, making the retrieval of specific mentions highly accurate and efficient.

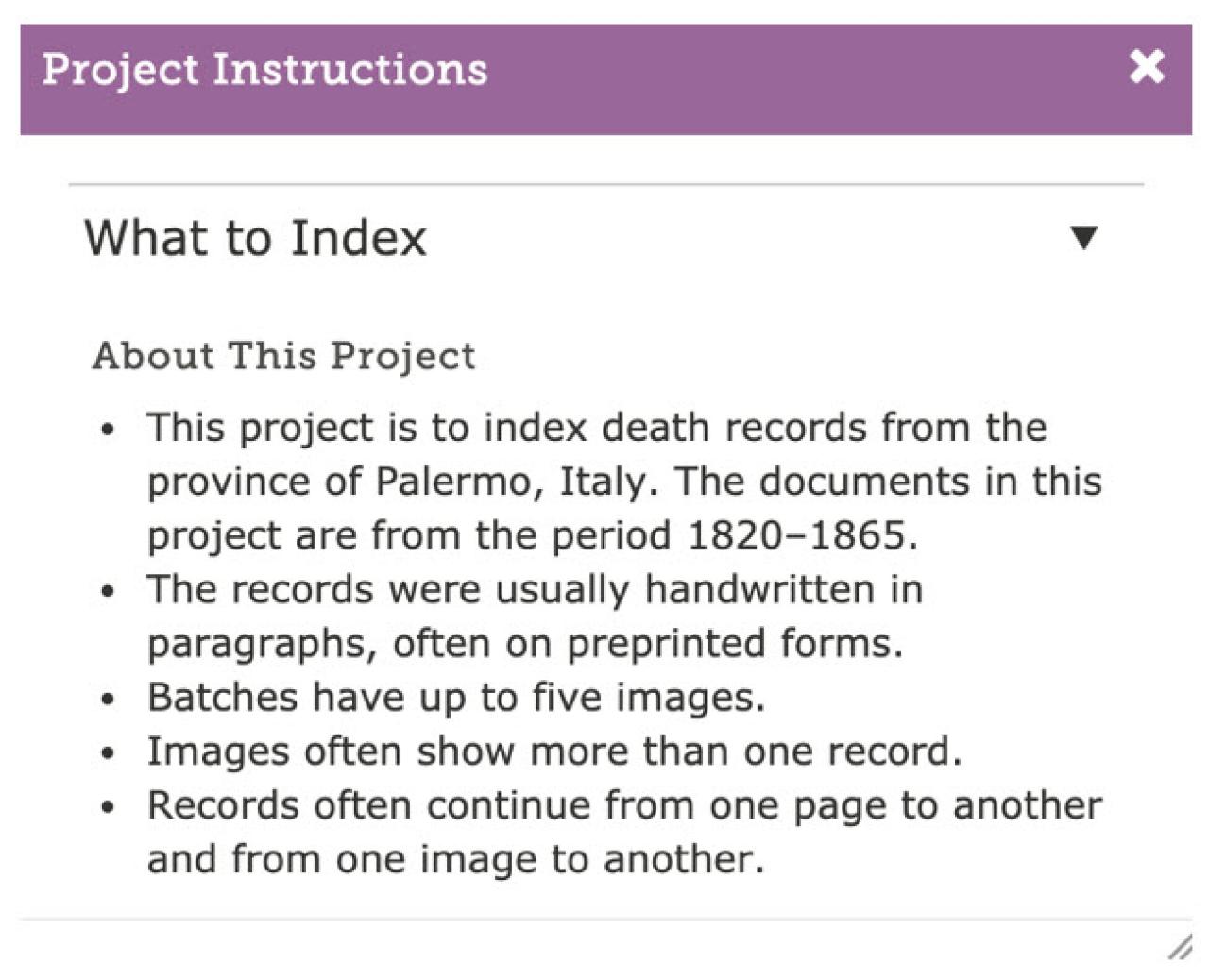

Practical Methods for Indexing Places

Indexing geographical locations is a crucial step in making textual information easily discoverable and navigable. This process involves systematically identifying and recording the names of places mentioned within a document or collection of documents, along with their corresponding locations in the text. A well-structured place index enhances research by allowing users to quickly find all references to a specific city, region, or country, thereby facilitating the study of historical events, migration patterns, or geographical descriptions.The creation of a place index begins with a thorough reading of the text to identify all mentions of geographical entities.

Each identified place name is then recorded, along with the page number(s), paragraph number(s), or specific sentence where it appears. This initial collection forms the raw data for the index. Subsequent steps involve standardizing these names, handling variations in historical and modern nomenclature, and finally, organizing this information into a usable format that links places to the context in which they are mentioned.

Standardizing Place Names

Standardization is paramount for an effective place index, ensuring that all variations of a place name are grouped together. This involves establishing a consistent format for recording names, typically including city, state or province, and country. For instance, if a text mentions “New York,” “NYC,” and “New York City,” the index should consolidate these under a single, preferred entry, such as “New York City, New York, USA.” This consistency prevents fragmented entries and improves search accuracy.Several methods can be employed for standardization:

- Hierarchical Naming: Always include the most specific location (e.g., city) followed by its administrative divisions (state/province, country). This creates a clear hierarchy and reduces ambiguity. For example, “Paris, Île-de-France, France” is more precise than just “Paris.”

- Official Names: Prioritize the official or most commonly recognized name for a place. This might involve consulting gazetteers, atlases, or official government sources.

- Abbreviation Management: Develop a policy for handling common abbreviations (e.g., “CA” for California, “UK” for United Kingdom) and ensure they are cross-referenced or expanded in the index.

- Geocoding: For digital indexing, consider using geocoding services to assign standardized latitude and longitude coordinates. This can help in resolving ambiguities and standardizing names based on geographical data.

Indexing Historical and Modern Place Names

Historical documents often present unique challenges due to the evolution of place names over time. A place that existed under one name in the past may be known by a different name today, or it may have been absorbed into a larger administrative region. Effectively indexing these requires acknowledging these temporal shifts.Strategies for handling historical and modern place names include:

- Cross-Referencing: If a historical name is used, provide a cross-reference to its modern equivalent, and vice versa. For example, an entry might read: “Constantinople (see Istanbul).” Conversely, an entry for Istanbul could note: “formerly Constantinople.”

- Date Ranges: For places with significant name changes, it can be beneficial to include date ranges indicating when a particular name was in use. This adds valuable context for researchers.

- Variant Spellings: Historical texts may also contain variant spellings of place names. These should be noted and, where possible, linked to the standardized entry.

- Subsumed Locations: When a historical entity (like a duchy or a small kingdom) is later incorporated into a larger country, the index should reflect this. An entry for a former kingdom might note its current status as a region within a modern nation. For example, an index entry for “Bohemia” could indicate its modern status as a historical region of the Czech Republic.

Organizing an Index Linking Places to Events or People

The most valuable place indexes go beyond simply listing locations; they connect these places to the specific events, people, or themes discussed in the text. This contextual linkage transforms the index from a simple directory into a powerful research tool.A well-organized example of such an index might appear as follows, using a tabular format for clarity:

| Place Name (Standardized) | Event/Person Mentioned | Context/Significance | Page/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rome, Lazio, Italy | Julius Caesar | Birthplace and center of political power. | pp. 15, 42, 110 |

| Rome, Lazio, Italy | Founding of the Roman Republic | Location of key senatorial debates and events. | p. 28 |

| Alexandria, Egypt | Library of Alexandria | Center of ancient learning and scholarship. | p. 75 |

| Alexandria, Egypt | Cleopatra VII | Residence and seat of her reign. | pp. 88, 95 |

| Constantinople (Istanbul), Turkey | Fall of Constantinople | Siege and conquest by the Ottoman Empire. | p. 150 |

| Constantinople (Istanbul), Turkey | Byzantine Empire | Capital city for over a millennium. | pp. 120-135 |

This structured approach allows users to quickly identify not only where events occurred or where individuals lived but also the significance of those places within the narrative. For instance, by looking at the entries for Rome, one can see its association with both a prominent historical figure and a major political event, as well as its broader role as a center of power.

Similarly, the entries for Constantinople highlight its dual identity and its critical role in historical transitions.

Advanced Indexing Techniques and Considerations

Beyond the foundational methods, a deeper dive into indexing people and places reveals sophisticated techniques and crucial considerations that can significantly enhance data discoverability and analytical power. As datasets grow in complexity and volume, the choice and application of indexing strategies become paramount for efficient information retrieval and meaningful insights. This section explores advanced approaches, potential challenges, and the role of semantic tools in refining person and place indexing.

Comparing Index Types for People and Places

Different indexing approaches offer distinct advantages and are suited to various data characteristics and user needs when dealing with information about people and places. Understanding their differences is key to selecting the most effective strategy.

- Full-Text Indexing: This method indexes every word in a text field. For people, it’s excellent for searching names, descriptions, or associated biographical details. For places, it allows searching for street names, city descriptions, or historical references within documents. It’s highly flexible but can lead to a large index size and potential for noise (irrelevant results) if not carefully managed with techniques like stemming and stop word removal.

- Metadata Indexing: This approach indexes specific, structured data fields that describe the content. For people, metadata could include fields like ‘given name,’ ‘surname,’ ‘birth date,’ ‘occupation,’ or ‘nationality.’ For places, it might involve ‘country,’ ‘state/province,’ ‘city,’ ‘latitude,’ ‘longitude,’ or ‘historical period.’ Metadata indexing is highly precise, enabling targeted searches and faceted navigation, but requires well-defined data structures and consistent data entry.

- Geospatial Indexing: Specifically designed for location data, this index type organizes spatial information, such as points, lines, and polygons, to enable efficient querying of geographic relationships (e.g., “find all places within 10 miles of this point,” “find people residing in this specific administrative boundary”). This is indispensable for analyzing spatial patterns and relationships.

- Named Entity Recognition (NER) Indexing: This technique automatically identifies and classifies named entities in unstructured text, such as person names (PER), locations (LOC), organizations (ORG), and dates (DATE). An index built on NER tags can allow for rapid retrieval of all mentions of a specific person or place, even if they are not explicitly tagged as metadata.

Challenges in Indexing Diverse and Complex Datasets

Indexing datasets related to people and places often presents unique challenges due to the inherent variability and complexity of the data itself. Addressing these challenges is vital for creating robust and accurate indexes.

- Ambiguity and Variation in Names: People’s names can have multiple spellings, nicknames, titles, and transliterations. Places can have historical names, official names, local names, and variations in spelling across different languages and scripts. This ambiguity requires sophisticated matching algorithms and disambiguation strategies. For example, “St. Petersburg” can refer to a city in Russia or a city in Florida, USA, and context is crucial for correct identification.

- Data Granularity and Scale: Datasets can range from a single address to complex geopolitical boundaries, and from individual biographical sketches to large population registries. Indexing at different levels of granularity (e.g., a specific building versus an entire city) and managing the sheer volume of data requires scalable indexing solutions.

- Temporal Dynamics: The attributes of people and places change over time. Birth dates, deaths, residences, and political boundaries are not static. Indexes need to account for these temporal shifts to provide accurate historical context and current information. For instance, indexing a historical residence requires noting the period it was occupied.

- Incomplete and Inconsistent Data: Real-world datasets are rarely perfect. Missing information, typos, and inconsistent formatting are common. Robust indexing systems must be able to handle these imperfections gracefully, often through data cleaning and standardization processes prior to indexing.

- Interconnectedness of Data: People are linked to places (residence, origin, workplaces), and places are linked to other places (administrative hierarchies, proximity). Indexes that can capture and leverage these relationships are more powerful for analytical purposes.

Role of Ontologies and Controlled Vocabularies in Enhancing Indexing

Ontologies and controlled vocabularies provide a structured, standardized framework that significantly enhances the precision, consistency, and interoperability of indexing for people and places. They move beyond simple matching to semantic understanding.

Ontologies define concepts and the relationships between them, while controlled vocabularies provide a predefined set of terms for consistent tagging.

- Standardization and Consistency: Controlled vocabularies, such as the Getty Thesaurus of Geographic Names (TGN) for places or established biographical dictionaries for people, offer a fixed list of preferred terms. This ensures that variations of a name or place are consistently mapped to a single, canonical entry in the index, reducing ambiguity. For example, instead of indexing “NYC,” “New York City,” and “The Big Apple” separately, an ontology could map them all to a single entity representing “New York City.”

- Semantic Richness and Inference: Ontologies define hierarchical relationships (e.g., “Paris is a city in France,” “France is a country in Europe”) and other semantic links (e.g., “Paris is the capital of France”). This allows indexes to support richer queries that leverage these relationships. A search for “European capitals” could automatically include Paris, Berlin, and Rome if their relationships to “Europe” and “capital city” are defined in the ontology.

- Disambiguation: By providing clear definitions and context for terms, ontologies and controlled vocabularies aid in disambiguating entities with similar names. For example, an ontology can differentiate between “Washington, D.C.” (the capital of the USA) and “Washington State” (a U.S. state) by their defined properties and relationships.

- Interoperability: When ontologies and controlled vocabularies are based on established standards (e.g., SKOS, CIDOC CRM), they facilitate data sharing and integration across different systems and organizations. This is crucial for large-scale research projects that aggregate data from multiple sources.

Hypothetical Scenario: Crucial Sophisticated Indexing for a Research Project

Consider a large-scale historical research project aiming to map the migratory patterns of artists and intellectuals across Europe during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This project involves analyzing vast archives of personal letters, exhibition catalogs, academic publications, and travel documents. Sophisticated indexing is not just beneficial but absolutely crucial for its success.The research team has digitized millions of documents, each containing references to individuals, cities, countries, and specific addresses.

- The Challenge: The raw data is highly unstructured and filled with variations. Personal letters might mention “my dear friend in Paris” or “the salon in Vienna I visited last spring.” Exhibition catalogs list artists with only their names and the cities where their works were displayed. Travel diaries might note “arrived in Berlin on the 14th of May” without a year.

Furthermore, the same person might be referred to by their first name, last name, or a pseudonym. Places might be referred to by their historical names (e.g., “Constantinople” instead of “Istanbul”) or informal descriptions.

- The Sophisticated Indexing Solution:

- Named Entity Recognition (NER) and Linking: The initial step involves applying advanced NER to identify all potential person and place names within the documents. Crucially, these identified entities are then linked to a knowledge graph.

- Knowledge Graph and Ontologies: A comprehensive knowledge graph is built, integrating data from existing historical databases, biographical dictionaries, and geographical gazetteers. This graph uses an ontology that defines relationships like ‘born in,’ ‘resided in,’ ‘traveled to,’ ‘associated with,’ ‘artist,’ ‘intellectual,’ ‘city,’ ‘country,’ and historical political entities.

- Temporal Indexing: Each person-place link is timestamped or associated with a date range derived from the context of the document. This allows tracking movements over specific periods. For example, a person might be indexed as ‘residing in Rome from 1905 to 1908.’

- Disambiguation Engine: A sophisticated disambiguation engine is employed. If “Gauguin” appears, the system, using contextual clues from the document and the knowledge graph, links it to the correct artist (Paul Gauguin) and distinguishes him from other individuals with the same surname. Similarly, if “Prague” is mentioned, the system uses temporal and contextual information to ensure it refers to the city during the relevant historical period, not a different entity or a modern re-contextualization.

- Geospatial Indexing: For specific addresses or known locations, geospatial indexing is used to plot them on historical maps, enabling spatial analysis of concentrations and travel routes.

- The Outcome: With this sophisticated indexing, researchers can perform complex queries such as:

- “Find all artists who resided in Paris between 1900 and 1910 and also traveled to Vienna at least twice during that period.”

- “Identify intellectuals who were active in literary circles in Berlin and Prague during the years leading up to World War I.”

- “Map the primary residences and travel destinations of individuals identified as ‘painters’ who were born in Italy.”

This advanced indexing approach transforms raw, disparate text into structured, queryable data, enabling the discovery of intricate migratory patterns, social networks, and intellectual exchanges that would be virtually impossible to uncover through manual analysis or simpler indexing methods. The ability to query based on semantic relationships and temporal context is the cornerstone of this project’s success.

Structuring Indexed Information for Clarity

Effective indexing relies not only on gathering the right data but also on presenting it in a way that is easily understandable and navigable. This section focuses on the structural aspects of organizing indexed information for both people and places, ensuring that key details are readily accessible and logically arranged. We will explore how to design data structures that enhance clarity and utility.The way indexed information is structured significantly impacts its usability.

By employing well-designed tables and organized lists, we can transform raw data into a coherent and informative resource. This approach is crucial for efficient retrieval and analysis, whether you are researching historical figures, genealogical records, or geographical datasets.

HTML Table Structure for Indexed People

A well-structured HTML table is fundamental for presenting indexed information about individuals. This structure allows for the clear display of various attributes associated with each person, facilitating quick comparisons and detailed examination. The table should include columns for key identifiers and descriptive information.

The following HTML table demonstrates a robust structure for indexing individuals. It includes essential fields that provide a comprehensive overview of each person indexed:

| Full Name | Date of Birth | Place of Birth | Occupation | Key Relationships | Notable Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jane Austen | December 16, 1775 | Steventon, Hampshire, England | Novelist | Daughter of George Austen and Cassandra Leigh; Sister to six brothers and one sister | Author of “Pride and Prejudice,” “Sense and Sensibility,” etc. |

| Alan Turing | June 23, 1912 | Maida Vale, London, England | Mathematician, Computer Scientist, Logician, Cryptanalyst | Son of Julius Mathison Turing and Sara Turing | Father of theoretical computer science and artificial intelligence; Broke Enigma code |

| Marie Curie | November 7, 1867 | Warsaw, Poland | Physicist and Chemist | Wife of Pierre Curie; Mother of Irène Joliot-Curie and Ève Curie | Pioneering research on radioactivity; First woman to win a Nobel Prize; Only person to win Nobel Prizes in two different scientific fields |

Responsive HTML Table for Indexed Locations

Presenting geographical data requires a flexible and responsive table structure that adapts to various screen sizes. This is particularly important for location data, which often includes coordinates, hierarchical information, and associated entities. A responsive table ensures that users can access this information seamlessly on desktops, tablets, and mobile devices.

The following HTML table is designed to be responsive and displays indexed data for geographical locations. It includes fields that are crucial for understanding the spatial and contextual aspects of a place:

| Location Name | Country | Latitude | Longitude | Elevation (m) | Related Entities | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eiffel Tower | France | 48.8584° N | 2.2945° E | 330 | Champ de Mars, Paris, Gustave Eiffel | Iconic wrought-iron lattice tower on the Champ de Mars in Paris. |

| Mount Everest | Nepal/China | 27.9861° N | 86.9226° E | 8848.86 | Himalayas, Sagarmatha National Park | Earth’s highest mountain above sea level. |

| Great Wall of China | China | 40.4319° N | 116.5704° E | Variable | Northern China, various dynasties | Series of fortifications made of stone, brick, tamped earth, wood, and other materials. |

Note: The <div class="table-responsive"> wrapper is a common technique in web development to make tables responsive. Actual responsiveness is typically achieved through CSS.

Common Indexing Fields for Individuals

Organizing the indexing of individuals requires a consistent set of fields that capture essential biographical information. These fields serve as the primary points of reference for identifying and distinguishing individuals within a dataset. A well-defined set of fields ensures uniformity and facilitates comprehensive data collection.

The following bullet points Artikel common indexing fields used for individuals, providing a standardized approach to biographical data collection:

- Full Name: The complete legal name of the individual, including any middle names or titles.

- Aliases/Known As: Any alternative names or pseudonyms the individual has been known by.

- Date of Birth: The specific day, month, and year of birth.

- Place of Birth: The city, region, and country where the individual was born.

- Date of Death: The specific day, month, and year of death, if applicable.

- Place of Death: The city, region, and country where the individual died, if applicable.

- Occupation/Profession: The primary work or trade of the individual.

- Education: Details about schooling, degrees, and institutions attended.

- Marital Status: Information on whether the individual is single, married, divorced, widowed, etc.

- Spouse(s): Names of any individuals married to the subject.

- Children: Names of the individual’s offspring.

- Parents: Names of the individual’s mother and father.

- Siblings: Names of brothers and sisters.

- Nationality: The country of citizenship.

- Residence: Places where the individual has lived.

- Notable Achievements/Contributions: Significant accomplishments, awards, or impacts.

- Biographical Notes: Any additional relevant information or context.

Typical Indexing Fields for Geographical Locations

Indexing geographical locations involves capturing information that defines their spatial attributes, administrative context, and significant characteristics. A standardized set of fields ensures that location data is precise, searchable, and useful for a wide range of applications, from mapping to historical research.

The following bullet points detail typical indexing fields used for geographical locations, ensuring comprehensive and accurate data representation:

- Location Name: The primary name of the geographical feature or place.

- Alternative Names/Local Names: Other names by which the location is known.

- Country: The sovereign state in which the location is situated.

- Region/State/Province: The major administrative division within the country.

- City/Town: The urban settlement containing the location.

- Latitude: The north-south coordinate on the Earth’s surface.

- Longitude: The east-west coordinate on the Earth’s surface.

- Elevation: The height of the location above sea level, typically in meters or feet.

- Geographical Coordinates (Decimal Degrees): A precise numerical representation of latitude and longitude.

- Area/Size: The physical extent of the location (e.g., square kilometers, acres).

- Population: The number of inhabitants, if applicable to a populated area.

- Type of Location: Categorization such as city, mountain, river, park, building, etc.

- Related Entities: Associated landmarks, organizations, historical figures, or natural features.

- Historical Significance: Information regarding the location’s role in historical events.

- Description: A brief overview of the location’s key features or purpose.

- Administrative Boundaries: Information about the political or administrative limits.

Closing Notes

In conclusion, mastering the art of indexing for people and places unlocks a new level of data organization and accessibility. By implementing the practical methods and advanced techniques discussed, you can transform complex datasets into easily navigable resources, making information retrieval more efficient and insightful than ever before. This comprehensive approach ensures that your indexed data is not only accurate but also readily usable for a wide range of applications.